International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 5, Issue 9, September-2014 672

ISSN 2229-5518

The Causal Relationship between Health and

Education Expenditures in Saudi Arabia

Faez S. Al-shihri

University of Dammam, Email: fshihri@ud.edu.sa

Abstract— The purpose of this research paper is to examine the causal relationship between health and education expenditures in Saudi Arabia over the period of 1990-2013, using multivariate Granger causality approaches. The result suggests that education Granger-causes health expenditure in both the short run and long run. The findings of this study implied that the Saudi government places preference on education expenditure rather than health. This preference is not unexpected as generally, an educated and knowledgeable society precedes a healthy one. Before a society has attained a relatively higher level of education, it is less aware of the importance of health. Thus, expenditure on education should lead expenditure on health.

Index Terms— Causality, health, Education, Saudi Arabia

—————————— ——————————

1 INTRODUCTION

One of the major macroeconomic policies in generating long term economic growth and development in a nation is to encourage and

maintain investments on human capital such as health and education. [1-5] Economists and policy planners usually claim that investments in health and education will eventually lead to better health and a higher level of education standard in the long term which

ultimately exerts a positive effect on labour force productivity and efficiency which in turn generate more national output growth and development. Although both forms of human capital investments are important, and thus expenditures are unavoidable, priority has to be set between them. This is because these expenditures usually involve huge sums and are mainly provided for by the public sector which usually has limited resources. Consequently, the equation of whether expenditure on education should lead expenditure on health, or vice versa, has always been the subject for intensive debates. On one hand, education positively affects health by enhancing the efficiency in health production, allocation of health resources, healthy life-styles society, and better-health-knowledge and information. On the other hand, health has a positive effect on education by contributing to increasing labour force productivity and efficiency.

From macroeconomics policies perspective, it is very important to analyze the direction of causality between health and education in formulating the necessary national development strategy, both in the short and long-term plans. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to empirically investigate the causal relationship between health and education expenditures in Saudi Arabia within the Granger causality framework using yearly data from 1990 to 2013. More specifically, this study attempts to examine the empirical question of whether funds should first be spent on health or education. In reality, resources are limited and hence preferences and choices have to be set by all consumers, firms, government and policymakers during the process of allocation of the available resources so that an optimal outcome could be attained.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: A brief study of previous empirical studies is presented in section 2. An overview of Saudi health and education expenditure is presented in section 3. Section 4

provides data and econometric approach used in the study. Empirical findings are discussed in section 5 and the main conclusions are stated in section 6.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

The economic literature suggests that there is a strong positive relationship between health and education.[6] Moreover, numerous empirical studies have been conducted to test the causal relationship between health and education in both developed and developing countries. Empirical studies[7-9] have focused on the causal relationship

between education and health based on the assumption that there is unidirectional causality running from education to health and has discounted the possibility that the reverse relationship can occur, while other studies have focused on the reverse causality based on the assumption that better-health enhances productivity through better health status of workers. Thus to these supporters, healthcare spending granger causes educational growth, all things being equal.

[1;11-13] Recent empirical studies, however, have focused on the interaction between the two variables based on the assumption that

there is bi-unidirectional (two-way) causal relationship between health and education. [4;14-15]

Broadly speaking, the review of existing literature reveals that empirical

studies on the causal relationship between health and education are mixed and inconclusive with results depending on the country or sample of countries, the time period as well as the methodology used. According to Tang and Lai[4], most of empirical studies on the relationship between health and education focused on developed countries while for developing countries, such studies are relatively limited. Apart from that, many of the early empirical studies have been performed using inappropriate econometric methodologies, as they did not take into consideration the time series properties of the data used. [6;9-10] According to Granger and Newbold[16], the estimated regression results are spurious if the series used are non-stationary and are not cointegrated. For this reason, the results provided by the aforementioned empirical studies are questionable and should be used with caution.

This research paper adds to the body of existing literature in a way that

the relationship between health and education for Middle East countries in general and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries in particular is rarely studied. Thus, by investigating empirically such a relationship in Saudi Arabia as oil-rich country, meaningful comparison can be made with the results from developed countries. In addition, the estimation of causality and its direction between health and education expenditures will be care out through the examination of stationarity properties for each series follows by examination of both the short and long run causal relationship of health and education by using

Granger[17] causality procedures.

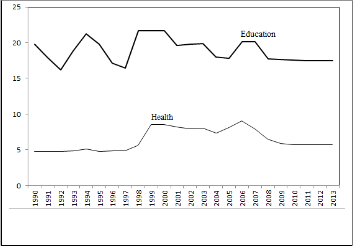

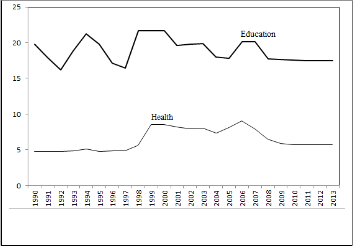

3 HEALTH AND EDUCATION EXPENDITURES IN SAUDI ARABIA Figure 1 shows the expenditure on education and health as a proportion of total government expenditure in Saudi Arabia for the period 1990 to 2013. It is evident that the proportion of government expenditure on education is consistently higher than that of health expenditure, implying that the government has recognized the relatively more important role of education in generating economic growth and development. It is aware of the fact that in order to create a

IJSER © 2014 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 5, Issue 9, September-2014 673

ISSN 2229-5518

stable and competitive economy, investments in human capital via education are essential.

The Johansen and Juselius[22] multivariate methodology to test for cointegration based on the vector autoregressive (VAR) system of n x

1 vector variables Xt is used:

𝑋𝑡 = 𝜇 + 𝛤1 + 𝑋𝑡=1+. … . +𝛤𝑝 𝑋𝑡=𝑝 + 𝜀𝑡 (3)

Where Xt =[Et ,Ht]', with Et ,Ht representing education and health

growth respectively, εt = [εE ,εH]' indicating structural shocks of

education and health growth.

Johansen and Juselius[22], using maximum likelihood, have developed two statistics to test the null of no cointegration. These statistics are the Trace statistic (λtrace) and the maximal eigenvalue statistic (λmax),

and computed as follow:

𝑝

𝜆𝑡𝑟𝑎𝑐𝑒 = 𝑇 � 𝐼𝑛[1 − 𝜆𝑖 ]

𝑖=𝑟+1

(4)

Fig. 1. Proportion of government development expenditure on education and health (percent)

During the decade from 1990 to 2000, the proportion of total expenditure on education increased from 19.78 per cent to 21.68 per cent, while that on health rose from 4.73 per cent to 8.57 per cent. The proportion of expenditures on education decreased from 19.61 per cent in 2001 to 17.46 per cent in 2011. The proportion of expenditure on health also decreased from 8.22 per cent to 5.73 per cent over the same period of 2001 to 201. By 2013, however, the proportion of expenditure on education and health has stabilized to about 17.44 per cent and 5.73 per cent, respectively.

total development expenditure to education and about 6.39 to health development over the period of 1990-2013. It is evident from Figure 1

𝜆𝑚𝑎𝑥 = 𝑇 𝐼𝑛[1 − 𝜆𝑟 +1] (5)

Where r is the number of cointegration vectors and λ1 ...λn are the N

square canonical correlations between Xt-p and Xt , the series being

ranged in a decreasing order so that λi> λj for i>j. Critical values are in Osterwald-Lenum. [23] If the computed statistics is lower than the critical value, one can reject the null hypothesis of no cointegration. The cointegration analysis developed by Johansen tests the hypothesis that

two variables have no equilibrium condition keeping them in proportion to each other in the long run. The lack of long run relationship provides evidence that the variables are not cointegrated.

In causality analysis, where no cointegration is found, classical

Granger causality tests is used. If, however, the series are cointegrated

then is appropriate to re-parameterize the model in the equivalent error correction model (ECM) form, otherwise inference may be invalid as the estimates may suffer from the spurious regression problem, in such a case causality testing can lead to erroneous conclusions. Furthermore, ECM-based causality tests offer the additional advantage that the source of causation can be identified, in the form of either short-run dynamics or disequilibrium long-run adjustment. The

variables[24-29]: in a multivariate case based on the regressions:

𝑠 𝑞

that, as a proportion of total development expenditure, education

∆𝐸𝑡 = ∅10 + � ∅11𝑖 ∆𝐸𝑡−𝑖 + � ∅12𝑖 ∆𝐻𝑡−𝑖 + 𝛿1 𝜇𝑡−1 + 𝜀1𝑡

(6)

expenditure far exceeded that of health. This pattern may be attributed

to the implementation of different national development policies that

𝑖 =1

𝑠

𝑖=1

𝑞

emphasized on the creation of knowledge-based society.

∆𝐻𝑡 = ∅20 + � ∅21𝑖 ∆𝐸𝑡−𝑖 + � ∅22𝑖 ∆𝐻𝑡−𝑖 + 𝛿2 𝜗𝑡 −1 + 𝜀2𝑡

(7)

𝑖 =1

𝑖 =1

4 DATA AND ECONOMETRIC APPROACH

4.1 Data

The annual data of public expenditures on health and education for Saudi Arabia are obtained directly from the W orld Bank’s W orld Development Indicators database.[18] The Consumer Price Index (CPI,

2005 = 100) was used to deflate the series to the real variables. Annual data have been used in this study because of the unavailability of higher frequency data (e.g., quarterly or monthly). Moreover, the use

of annual data will also avoid the seasonal bias problems. The annual data covered the period 1990 to 2013. All data used in this study are in natural logarithm form.

4.2 Econometric Approach

Prior to test for cointegration and causality, unit root tests are

performed on each variable to determine the order of integration. Both the ADF test[19] and PP test[20] are used to check for unit root and stationarity, and is conducted from the estimation of the following equations:

𝑝

Where Et and Ht are difference stationary and cointegrated with μt-1

and ϑt-1 representing the lagged values of the error terms from cointegrating regressions. The random errors are given by ε1t and ε2t, and capture all short-run deviation from H to E and from E to H, s and q are determined by Akaike information criterion (AIC). The lagged changes in the independent variable in equation 6 and 7 can be interpreted as representing the short-run causal impact, while the error terms provide the adjustment of ∆E and ∆H towards their respective long-run equilibrium. Using the above ECM-equations three types of causal relationships can emerge, (i) bidirectional causality (that is two- way feedback causal relationship between variables), (b) unidirectional causality (that is one-way causality direction; only one variable causes the other, and (c) no causality; the two variables do not have causality direction.

5 EMPIRICAL RESULTS

The first step in our empirical analysis is an investigation of the order of integration, I(d) of the two variables under consideration. This is because the estimated relationship may be spurious if the variables are

∆𝐸𝑡 = 𝜌0 + 𝜌1 𝐸𝑡−1 + 𝜌2𝑡 + � ∅𝑘 ∆𝐸𝑡−1 + 𝜀𝑡

(1)

non-stationary.

The conventional unit root tests (i.e. ADF and PP)

𝑖=1

𝑝

∆𝐻𝑡 = 𝜌0 + 𝜌1𝐻𝑡−1 + 𝜌2 𝑡 + � ∅𝑘 ∆𝐻𝑡−1 + 𝜀𝑡

𝑖=1

(2)

suggest that the two estimated series are integrated of order one, that

is, they are I(1) processes. Table 1 shows the summary of the ADF

and PP unit root test results for the variables.

Where ∆ is the first difference operator, εt is a white noise error term, t

is a time trend, and p is chosen such that the residuals are serially

uncorrelated. The null hypothesis of non stationarity is rejected if

[21]

Table 1: Unit Root Test

ρ1 < 0 and statistically significant.

IJSER © 2014 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 5, Issue 9, September-2014 674

ISSN 2229-5518

| (0.530) | (0.000) | (0.736) | (0.000) |

Notes: Figures in the parenthesis are the probability value. Source: Author estimation using EViews8.

The above results demonstrates that both variables of interest are integrated of order one and are thus, I(1) processes. Furthermore, this result is in line with the findings of Nelson and Plosser[30] which showed that most of the macroeconomic variables are non-stationary at level,

but are stationary after first differencing. W ith these findings, the Granger causality tests will be used to examine the short and long run causal relationship between health and education expenditures in Saudi Arabia.

A common practice in performing causality tests is to determine the optimal lag order for the vector autoregressive (VAR) model. In order to

ascertain the optimal lag combination for the VAR models, the Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) is employed. The AIC performs better than other criteria, in particular when the estimated sample size is small. [31-

32] However, the AIC test suggests one lag length is the best to present the dynamic structure of the VAR system.

The Johansen test for cointegration indicates one cointegrating

relationships between the variables (Table 2). That means long-run relationships exist between the two variables. Given the results from the cointegration test an EC-VAR model is appropriate in the causality analyses.

Table 2: Cointegration Test

Note: * denote significant at 1% level. Source: Author estimation using EViews8.

The results of the causality analyses are reported in Table 3. For the short run causality test, the Granger causality test results revealed that the education expenditure Granger-causes health expenditure in Saudi Arabia, but there is no evidence of the reverse causation. For the case of long run causality, the results also indicate a unidirectional causality running from education to health expenditures in Saudi Arabia.

A number of diagnostic tests are also conducted to ascertain the

suitability of the models (Panel B-Table 3). Specifically, the Breusch- Godfrey LM test statistics showed that the null hypothesis of no autocorrelation problem cannot be rejected. Thus the estimated models are free from serious autocorrelation problem. The ARCH LM test showed that the residuals are free from the autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity (ARCH) problem.

The empirical evidence appears to suggest that between the two types of human capital investments, investments on education takes precedence over that on health care in Saudi Arabia during the period

1990 to 2013. This is consistent to the finding of Forster et al. [33] for the case of the United Kingdom and Tang and Lai[4] in the case of

Malaysia. An implication of this precedence is that relatively more

educated people are knowledgeable about the importance of health compared to less educated ones. They will take necessary steps to ensure that they remain healthy so as to reduce the expenditure on medical services. W hen confronted with the choice, investing relatively more on education rather than health services would be a more proactive and sensible planning policy. A knowledgeable society is necessary and sufficient condition for a healthier society. Thus, policy initiatives which place importance on education expenditure should be implemented. This would exert positive externalities on other parts of society, including its health aspect, thus eventually generating sustainable economic growth and development.

Table 3: Causality Test

Panel A: Short run and long run Granger causality

χ2 - statistics

Null hypothesis ECT

Panel B: Stability test

LM test Normality test Heteroscedasticity

ARCH-test

Equation (6) 1.065 3.522 0.948

Equation (7) 0.436 5.135 0.780

Notes: *, **are significant at 1% and 5%. Residual is not serially correlated using Bruesh-Godfrey serial correlation LM test. Equations pass the normality test as Jarques-Bera statistic shown that residual is normally distributed and non-heteroscedastic using Bruesh-Pagan-

Godfrey method. The notation Health ↛ Education represents the null

hypothesis: Health Expenditure does not Granger-cause Education

Expenditure. A similar interpretation follows for the reverse test. Source: Author estimation using EViews8.

6 CONCLUSIONS

The intention of this research paper is to examine whether expenditure

on health or education takes precedence in Saudi Arabia during the period of 1990 to 2013. The empirical analysis involves the use of multivariate approach. The Augmented Dickey Fuller (ADF) and Phillips and Perron (PP) tests were used to check for stationarity of time series of variables under investigation. The Johansen and Juselius co-integration test was performed to obtain the number of co- integrating vector(s) between series, and the VECM Granger causality was employed to examine the nature of interdependence between variables. The results have important implications that need to be considered by policymakers in modelling economic growth and development policies for Saudi Arabian economy.

The results consistently showed that education expenditure Granger-

causes health expenditure, but the reverse causation does not hold. This finding conforms to most studies in various countries that showed the positive association between education and health. The general observation is that low educational attainment leads to poor health. Given the unidirectional causality from education to health expenditures, it is apparent that when policy planners are confronted by a choice between education and health expenditure, a rational policy decision would be to place more importance on education expenditure. Past education expenditure will have a positive effect on health, thus reducing health care costs to society.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to extend my sincere gratitude to Dr. Abdulkarim K. Alhowaish for his valuable contribution in revising the manuscript and

for his suggestions and comments in preparing this research study.

REFERENCES

1. Mushkin, S.J. (1962), Health as an investment, Journal of Political

Economy, 70(5): 129-157

2. Barro, R.J. (2001), Human capital and growth, American

Economic Review, 91(2): 12-17

3. Pereira, J., Aubyn, M.S. (2009), W hat level of education matters most for growth? Evidence from Portugal, Economics of Education Review, 28(1): 67-73

4. Tang, C.F. and Lai, Y.W . (2011), The Causal Relationship between Health and Education Expenditures in Malaysia, Theoretical and Applied Economics, 8(561): 61-74

5. Alhowaish, A.K. (2014), Healthcare Spending and Economic

Growth in Saudi Arabia: A Granger Causality Approach,

Short run (W ald test)

t-1

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, 5(1):

Health ↛ Education 0.039 -0.094

Education ↛ Health 3.591** -1.573*

1471-74

IJSER © 2014 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 5, Issue 9, September-2014 675

ISSN 2229-5518

6. Ross, C.E. W u, C.L. (1995), The links between education and health, American Sociological Review, 60(5): 719-645

7. Grossman, M. (1972), On the concept of health capital and the demand for health, Journal of Political Economy, 80(2): 223-255

8. Perron, P. (1989), The great crash, the oil price shock and the unit root hypothesis, Econometrica, 57(6): 1361-1401

9. Arendt, J.N. (2005), Does education cause better health? A panel data analysis using school reforms for identification, Economics of Education Review, 24(2): 149-160

10. Silles, M.A. (2009), The causal effect of education on health: Evidence from the United Kingdom, Economics of Education Review, 28(1): 122-128

11. Kenkel, D.S. (1991), Health behavior, health knowledge, and schooling, Journal of Political Economy, 99(2): 287-305

12. Hartog, J., and Oosterbeek, H. (1998), Health, wealth and happiness: W hy pursue a higher education?, Economics of Education Review, 17(3): 245-256

13. Groot, W ., and M. van den Brink, (2007), The health effect of education, Economics of Education Review, 26(2): 186-200

14. Cowell, A.J. (2006), The relationship between education and health behavior: Some empirical evidence, Health Economics,

15(2): 125-146

15. Sequeire, T.N. (2007), Does health cause schooling or does schooling cause health?, Department of Management and Economics Discussion Paper, No. 01/2007, Portugal: Universidade da Beira Interior

16. Granger, C.W .J., and Newbold, P. (1974), Spurious regression in econometrics, Journal of Econometrics, 2(2): 111-120

17. Granger, C.W .J. (1969), Investigating Causal Relations by

Econometric Models and Cross-Spectral Methods, Econometrica,

37(3): 424-438

18. W orld Health Organization (2001) Macroeconomics and Health: Investing in Health for Economic Development, Available from: http://www.who.int/whosis/cmh. [Last accessed on 2013

December 4].

19. Dickey, D.A. and Fuller, W .A. (1979), Distributions of the Estimators for Autoregressive Time Series with a Unit Root, Journal of the American Statistical Association, 74(5): 427-31

20. Phillip P.C.B. and Perron P. (1988), Testing for a unit root in time series regression, Biometrika, 75(3): 335-346

21. MacKinnon, J. J. (1991) Critical values for cointegration tests, in Readings in cointegration (Ed) R.F. Engle and Granger, C.W . Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 267-276

22. Johansen, S., and Juselius, K. (1990), Maximum Likelihood Estimation and Inference on Cointegration with applications to the Demand for Money, Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics,

52(2): 169-210.

23. Osterwald-Lenum, M. (1992), A Note with Quantiles of the Asymptotic Distribution of the Maximum Likelihood Cointegration Rank Test Statistics, Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics,

54(4): 461 -472

24. Granger, C.W .J. (1963), Processes involving feedback, Information and Control, 6(1): 28-48

25. Granger, C.W .J. (1986), Developments in the study of cointegrated economic variables, Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 48, 213-228

26. Granger, C.W .J. (1988), Causality, Cointegration, and Control, Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 12(4): 551-559

27. Hendry, D. F., Pagan, A. R., and Sargan, J. D. (1984), Dynamic specification, in Griliches, & Intriligator (1984), Ch. 18. Reprinted in Hendry, D. F., Econometrics: Alchemy or Science? Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1993, and Oxford University Press, 2000

28. Engle, R.F. and Granger, C.W .J, (1987), Cointegration and error correction: representation, estimation and testing, Econometrica,

55(3): 251-76

29. Johansen, S. (1988), Statistical Analysis of Cointegrating Vectors, Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control , 12(4): 231-254

30. Nelson, C.R., and Plosser, C.I. (1982), Trends and random walks in macroeconomic time series: Some evidence and implications, Journal of Monetary Economics, 10(2): 139-162

31. Liew, K.S. (2004), W hich lag length selection criteria should we employed?, Economics Bulletin, 3(1):1-9

32. Lütkepohl, H. (2005), New Introduction to Multiple Time Series

Analysis, Germany: Springer-Verlag.

33. Forster, D.P., Francis, B.J., Frost, C.E.B., and Heath, P.J. (1981), Health and education expenditure in the United Kingdom: W hat priority?, Health Policy and Education, 2(1): 77-84

IJSER © 2014 http://www.ijser.org