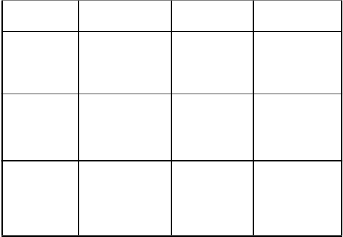

Table 1 (Regression Analysis – ANOVA)

The research paper published by IJSER journal is about The Importance of Firm Ownership on CEO Compensation: An Empirical Study on New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) Companies 1

ISSN 2229-5518

Nulla, Yusuf Mohammed, D.Phil. & Ph.D. Student, MSc, MBA, B.Comm.

Abstract— This important study in Executive Compensation topic investigated the importance of Firm Ownership on the CEO Compensation system in the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) companies. This research had compared the CEO Compensation System of the Owner-Managed and the Management-Controlled companies from 2005 to 2010. The research question for this study was: is there a relationship between the CEO Cash Compensation, the Firm Size, the Accounting Firm Performance, and the Corporate Governanc e, among the Owner-Managed and the Management-Controlled companies?. It was found that, there was a relationship between the CEO Salary, the CEO Bonus, the Total Compensation, the Firm Size, the Accounting Firm Performance, and the Corporate Governance, among the Owner-Managed and the Management-Controlled companies.

Index Terms— CEO Compensation, Accounting Performance, Corporate Governance, Corporate Ownership, Owner -Controlled CEO Compensation, Management-Controlled CEO Compensation, and NYSE Compensation.

—————————— ——————————

he purpose of this research is to understand in-depth the importance of the Firm Ownership on the CEO Compensa- tion system in the NYSE companies, from the period 2005 to

2010. That is, how the Owner-Controlled and the Management- Controlled companies have an effect on the CEO Compensation System. This interesting and important study in Executive com- pensation area will reveal some scientific methodologies or trends to understand the nature of the CEO contract under respective ownerships. This study was conducted also in the influence of, over the past decade, the United States public had raised con- cerns over the huge bonuses declared to the CEOs by their board of directors. The failure to understand the determinants of the CEO compensation by the public had led to blaming the CEOs of rent grabbing; misused of its power towards board; and its mo- nopolization of the compensation system. Thus, these ever grow- ing concerns bring to the foreground conclusion the need to fur- ther study the CEO Compensation System especially the effect of the type of ownership on the CEO Compensation, as one impor- tant corner of the executive compensation study.

The CEOs and the other executives would like to elimi-

nate the risk exposure in their compensation packages by de-

coupling their pay for performance and linking it to a more stable factor, the Firm Size. This strategy indeed deviates from obtaining the optimum results from the principal-agent contracting. In gen- eral, the past studies had found a strong relationship between the CEO Compensation and the Firm Size but the correlation results were ranged from the nil to the strong positive ratios. The va- riables used in the past studies as a proxy for the Firm Size were either the Total Sales, the Total Number of Employees, or the To- tal Assets. Therefore, the Firm Size needs to be studied with the CEO Cash Compensation on an extensive basis such as: using both the Total Sales and the Total Number of Employees.

The most researched topic in the executive compensa-

tion is between the CEO Compensation and the Firm Perfor- mance. Although the executive compensation and the firm per- formance had been the subject of debate amongst the academic, there was little consensus on the precise nature of the relationship as such, further researched in greater detail need to be conducted to understand in the finer terms the true extent of the relationship between them. As such, this research had unprecedentedly used eight variables to attest with the CEO compensation, that is, the Return on Assets (ROA), the Return on Equity (ROE), the Earn- ings per Share (EPS), the Cash Flow per Share (CFPS), the Net Profit Margin (NPM), the Book Value per Common Shares Out- standing (BVCSO), and the Market Value per Common Shares Outstanding (MVCSO).

The relationship between the CEO compensation and

the Corporate Governance (CEO Power) was not attested exten-

sively in the past, especially in Canada. In fact, only few credible

researched papers were available for to study. That is, the CEO Power only had been the subject of the recent focus among the researchers, primarily due to the effect of the researchers failed to find the strong relationship between the CEO Compensation, the Firm Size, and the Firm Performance. The variables used in the past studies as a proxy for the Corporate Governance such as, the CEO Age; the CEO Tenure; and the CEO Tenure, were found to have the weak to the negligible relationship with the CEO Com- pensation. In addition, the third party data collection, the lower quality of the sampling population focus such as at the industry level, and the use of different statistical methods, all had led to the divergence in the results. Therefore, the Corporate Gover- nance needs to be studied with the CEO compensation on an ex- tensive basis such as by using, the CEO Age, the CEO Shares Outstanding, the CEO Share Value, the CEO Tenure, the CEO Turnover, the Management 5 percent ownership, and the Indi- viduals/Institutions 5 percent ownership.

IJSER © 2012

The research paper published by IJSER journal is about The Importance of Firm Ownership on CEO Compensation: An Empirical Study on New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) Companies 2

ISSN 2229-5518

Therefore, all the above components attestations will as- sist in understanding the true nature of the ownership effect on

to 2009.

There was a substantial evidence that the firm size was a

the CEO Compensation. That is, the companies will be grouped on the basis of Owner-Managed and Management-Controlled and then perform attestations between the CEO Compensation, the Firm Size, the Firm Performance, and the Corporate Gover- nance, to arrive at comparative conclusions.

Gomez-Mejia and Barkema (1998) defined the relationship as: A

positive relationship between the CEO compensation and the firm performance would be consistent with the agency theory, the dominant paradigm in this stream of research. The CEOs cash incentives have a strong relationship with the firm size as the CEOs in larger companies make higher income than the CEOs in the smaller companies. This is supported by Finkelstein and Hambrick (1996) that the firm size is related to the level of executive compensation. According to Tosi and Gomez-Mejia (1994) the measurement of the firm size was the composite score of the standardized values of reported the total sales and the number of employees. Shafer (1998) showed that the pay sensitiv- ity (measured as the dollar change in CEO wealth per dollar change in firm value) falls with the square root of the firm size. That is, the CEO incentives are 10 times higher for a $10 billion firm than for a $100 million firm.

From the famous meta-analysis conducted by Tosi,

Werner, Katz, and Gomez-Mejia (2000) they found that the esti- mated correlation between the CEO pay and the aggregate firm size factor is .643, signifying that the firm size accounts for over

40% of the variance in CEO pay. Similarly, the adjusted compo- site correlation between the change in the CEO pay and the

change in the Firm Size is .225, accounting for about 5% of the variance in changes in the CEO pay. In addition, they found that the CEOs can exert more influence over the Firm Size than the CEO Performance, and therefore, they would prefer to use the firm size as the criterion for the compensation purposes. Firstly, this is supported by Simmons, & Wright (1990) that the CEO pay increases considerably following a major acquisition even when the firm performance suffers. Secondly, Kostiuk (1990) argued that the greater the size may be used to legitimize the higher CEO pays by appealing to rationalizations to justify a size premium. Rationalizations may include: the greater organizational com- plexity; and more CEO human capital required to run the busi- ness (Agarwal, 1981). Thirdly, executives are risk averse. They can reduce or eliminate risk exposure in their compensation package by decoupling their pay from performance and linking it to a more stable factor, the firm size (Dyl, 1988; and McEachern,

1975). In addition, according to Gomez-Mejia (1994), a host of structural factors and the pragmatic problems make it difficult for the corporations to effectively control executives, leading to the compensation packages that are more closely tied to the firm size than the performance. According to Sigler (2011), the firm size appears to be the most significant factor in determining the level of the total CEO compensation. His examination was based on the 280 firms listed on the New York Stock Exchange from 2006

major determinant of the CEO pay Fox (1983). Finkelstein and Hambrick (1989) believed that the bigger firms tend to pay more because the CEO oversees substantial resources, rather than be- cause of their number of hierarchical pay levels. This theory was explained in another form by Fox (1983) that the CEOs are paid more in the larger firms primarily due to its leadership demand and more hierarchical layers exist in the larger firms. However, the results have varied from nil to strong positive associations between the CEO compensation and the larger firms (Finkelstein and Hambrick, 1989).

Gomez-Mejia, Tosi, and Hinkin (1987) believed that the

firm size was a less risky basis for setting executives‘ pay than performance, which was subject to many uncontrollable forces outside the managerial sphere of influence. Similarly, McEachern (1975) argued that the CEOs in management-controlled firms will prefer to avoid the risk of tying pay to the performance, therefore, the firm size, which was likely to vary less than performance, will most affect pay. This was supported by Hambrick and Finkels- tein (1995) and Gomez-Mejia et al. (1987) that the firm size was related to the total pay in the management-controlled firms but not the owner-controlled firms suggesting that the managerial control was a moderator of the pay-size relationship. In the own- er-controlled firms, the large share of compensation should be contingent on the firm performance than was base salary (Go- mez-Mezia, Tosi, and Hinkin, 1987). Murphy (1985) showed that the holding the value of a firm constant, a firm whose sales grow by 10 percent will increase the salary and bonus of its CEO by between 2 percent and 3 percent. These findings suggested that the size-pay relation is causal. It also suggests that CEOs can in- crease their pay by increasing the firm-size, even when the in- crease in size reduces the firm‘s market value. Prasad (1974) be- lieved that executive salaries appear to be far more closely corre- lated with the scale of operations of the firm than its profitability. He also believed that the executive compensation was primarily a reward for the past sales performance and was not necessarily an incentive for future sales efforts.

Tosi et al. (2000) believed that the most of the studies

conducted by scholars found that the executive pay as a control

mechanism are remarkably inconsistent not only with the theory but with each other. This is supported by studies conducted by Belkaoui and Picur (1993), David, Koachhar, and Levitas (1998),

and Gray and Cannella (1997) that the correlations between the firm size and the CEO pay are as low as .107, .110, and .170, while studies conducted by Boyd (1994), and Finkelstein and Boyd (1998) reported correlations of .62, .50, and .42.

The CEO cash compensation is generally believed to be weakly related to the firm performance, according to a majority of studies conducted in the United States and the UK. It is believed that the CEO power and weaker governance play an important role in the weak relationship between the CEO cash compensation and the firm performance. Henderson and Fredrickson (1996) stated that while the CEO total pay may be unrelated to performance, it is

IJSER © 2012

The research paper published by IJSER journal is about The Importance of Firm Ownership on CEO Compensation: An Empirical Study on New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) Companies 3

ISSN 2229-5518

related to the organizational complexity that they manage. Like- wise, other similar studies conducted by Murphy (1985); Jensen and Murphy (1990); and Joskow and Rose (1994) supported this nature of the relationship.

Jensen and Murphy (1990) argued that incentive align- ment as an explanatory agency construct for the CEO pay is weakly supported at best. That is, objective provisions of princip- al-agent contract cannot be comprehensive enough to effectively create a strong direct CEO pay and performance relationship. They found that the pay performance sensitivity for the execu- tives is approximately $3.25 per $1000 change in the shareholder wealth, the ―small for an occupation in which the incentive pay is expected to play an important role‖. This is supported by the legendary work of Tosi, Werner, Katz, and Gomez-Mejia (2000) on pay studies in the form of the meta-analysis that the overall ratio of the change in the CEO pay and change in the financial performance is 0.203, an accounting for about 4% of the variance. The estimated true correlation between the CEO pay and the Re- turn on Equity is .212. And the estimated true correlation be- tween the CEO pay and the Total Assets is 0.117. Thus, these oth- er financial measures account for less than the 2% of the variance in the CEO pay levels. This weak relationship is explained by Borman & Motowidlo (1993); and Rosen (1990), who stated that the archival performance data focuses only on a small portion of the CEO‘s job performance requirements and therefore it is diffi- cult to form an overall conclusion.

According to Jensen and Murphy (1990) it is possible

that the CEO bonuses are strongly tied to an unexamined or un- observable measure of the performance. If the bonuses depend on the performance measures observable only to the board of direc- tors and are highly variable, they could provide significant incen- tives. One way to detect the existence of such ―phantom‖ perfor- mance measures is to examine the magnitude of year-to-year fluctuations in the CEO compensation. The large swings in the CEO pay from year to year were consistent with the existence of an overlooked but important performance measure: small annual changes in the CEO pay suggested that the CEO pay was essen- tially unrelated to all the relevant performance measures. Fur- thermore, they argued that although bonuses represent 50% of the CEO salary, such bonuses were awarded in ways that were not highly sensitive to performance as measured by changes in the market value of the equity, the accounting earnings, or the sales. In addition, they found that, that while more of the varia- tion in the CEO pay could be explained by the changes in the accounting profits than the stock market value, however, the pay- performance sensitivity remains insignificant.

Jensen and Murphy (1990) found in their study that the

CEO received an average pay increase of $31,700 in years when

the shareholders earned the zero return, and received on average an additional 1.35¢ per $1,000 increase in the shareholder‘s wealth. These estimates are comparable to those of Murphy (1985 and 1986); Coughlan and Schmidt (1985); and Gibbons and Mur- phy (1990), who found pay-performance elasticity of approx- imately 0.1 – the salaries and the bonuses increased by about one percent for every ten percent rise in the value of the firm. Addi- tionally, they stated that the average pay increase for the CEO whose shareholders gain $400 million was $37,300, compared to

an average pay increase of $26,500 for the CEO whose sharehold- ers lose $400 million. Their Forbes study was based on the Execu- tive Compensation Surveys covered from the period 1974 to 1986. Jensen and Murphy (1990) provided one explanation for the small pay-performance sensitivity was that, the boards have fair- ly good information regarding the managerial activity and there- fore the weight on output was small relative to the weight on input.

On the other hand, Jensen and Zimmerman (1985) ar- gued that the evidence was inconsistent with the view that execu- tive compensation is unrelated to the firm performance and that

the executive compensation plans enrich managers at the expense of shareholders. This argument was supported by Mehran (1995) reported that the CEO pay structure was positively related to same-year performance. In addition, Gibbons and Murphy (1990) also found in their study that the CEO salaries and the bonuses were positively and significantly related to the firm performance as measured by the rate of return on common stock. That is, CEO pay changes by about 1.6% for each 10% return on the common stock. In addition, they found that the CEO cash compensation was positively related to the firm performance and negatively related to the industry performance, ceteris paribus. Similarly, Antle and Smith (1986) found no relation between the salary and the bonus and the industry returns. Blanchard, Lopez-de-Silanes and Shleifer (1994); and Bertrand and Mullainathan (2001) argued that there was an evidence that CEO cash compensation increases when firm profits rise for reasons that clearly have nothing to do with managers‘ efforts.

Murphy (1985), and Jensen and Murphy (1990) found a significant relationship between the level of pay (measured by changes in executive wealth) and the performance (measured by changes in firm value). At the same time, Jensen and Murphy (1990) argued that the failure to include the cash performance measure in the pay-performance studies may thus create the im- pression that the management compensation was unresponsive to the corporate performance. Similarly, Iyengar, Raghavan J. (2000) found that on the average, the level of the CEO cash com- pensation was positively related to the firms‘ level of the operat- ing cash flows. On the other hand, Carpenter and Sanders (2002) argued that the CEO‘s total pay may be unrelated to the perfor- mance, but it may relate to the organizational complexity that they manage. This argument was supported by Jensen and Mur- phy (1989) as he provided additional hypothesis in the form of political forces factor in the contracting process which implicitly regulate executive compensation by constraining the type of the contracts that can be written between the management and the shareholders. These political forces, operating in both the political sector and within organizations, appear to be important but were difficult to document because they operate in informal and indi- rect ways. The public disapproval of high rewards seems to have truncated the upper tail of the earnings distribution of the corpo- rate executives. The equilibrium in the managerial labor market then prohibits the large penalties for the poor performance and as a result the dependence of pay on performance was decreased. Their findings that, the pay-performance relation; the raw varia- bility of the pay changes; and the inflation-adjusted pay levels, have declined substantially since the1930s, was consistent with

IJSER © 2012

The research paper published by IJSER journal is about The Importance of Firm Ownership on CEO Compensation: An Empirical Study on New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) Companies 4

ISSN 2229-5518

such implicit regulation.

Mehran (1995) found that the companies in which the

CEO compensation was relatively sensitive to the firm perfor-

mance tend to produce higher returns for the shareholders than

the companies in which the relationship between the CEO pay

and the performance was weak. Lambert and Larcker (1987) and

Sloan (1993) found in their empirical studies that there was a pos- itive relation between the CEO compensation and the stock re- turns. Jensen and Murphy (1990) believed that the cash compen- sation should be structured to provide big rewards for the out- standing performance and the meaningful penalties for the poor performance. Also, they believed that weak link between the CEO cash compensation and the corporate performance would be less troubling if the CEOs owned a large percentage of corpo- rate equity.

According to McEachern (1975); Allen (1981); Amould

(1985); Gomez-Mejia, Tosi, and Hinkin (1987); Dyl (1988); Gomez- Mejia and Tosi (1989); and Kroll, Simmons, and Wright (1989), the relationship between the executive pay and the performance may be stronger in the owner-controlled than in the management- controlled firms. Werner and Tosi (1995) showed that the manag- ers in widely held firms are paid more than the managers in the closely held firms through the higher salaries, the higher bonuses, and the higher long-term incentives. Dyl (1988) argued that that there is a downside hedge in the pay of CEOs in management- controlled firms, given that it is more strongly related to the firm size, not the performance. He also believed that, the owner- controlled firms will seek to transfer some of the risks borne to the managers, and this should be reflected in their compensation policies (Antle and Smith, 1986).

It is believed that the CEO in the larger firms tends to own less stock and have less compensation-based incentives than the CEOs in the smaller firms. This is supported by Jensen and Mur- phy (1985) by stating that our all-inclusive estimate of the pay- performance sensitivity for the CEOs in the firms in the top half of our sample (ranked by market value) is $1.85 per $1,000, com- pared to $8.05 per $1,000 for the CEOs in the firms in the bottom half of our sample. In addition, they (1990) argued that as a per- centage of the total corporate value, the CEO share ownership had never been very high. The median CEO of one of the nation‘s

250 largest public companies own shares worth just over $2.4 million – again, less than 0.07% of the company‘s market value. Also, 9 out of 10 CEO own less than 1% of their company‘s stock, while fewer than 1 in 20 owns more than 5% of the company‘s outstanding shares. Jensen and Murphy (1990) found in their study that the most powerful link between the shareholder wealth and the executive wealth was direct ownership of the shares by the CEO. They found, on average, the CEOs receive about 50% of their base pay in the form of the bonuses. They ar- gued that most experts assessed the CEO stock ownership in terms of the dollar value of the CEO‘s holdings or the value of his shares as a percentage of his annual cash compensation. Howev- er, they also argued that neither of these measures were relevant in the CEO incentive determination. They believed that the per-

centage of the company‘s outstanding shares of the CEO owner- ship influences the CEO‘s pay. However, their statistical analysis found no correlation between the CEO stock ownership and pay- for-performance sensitivity in cash compensation. That is, the board of directors ignore the CEO stock ownership when struc- turing incentive plans. This is supported by Cyert, Kang, and Kumar (2002) study who found a negative correlation between the equity ownership of the largest shareholder and the amount of the CEO compensation: doubling the percentage ownership of the outside shareholder reduces the non-salary compensation by

12-14 percent. This was supported to the great extent by Murphy

and Jensen (1990) who found in their study that there was a small and insignificant positive coefficient of the ownership-interaction variable exist, which implied that the relation between compensa- tion and performance was independent of an executive‘s stock holdings. The result that the pay-performance relation was not affected by stock ownership seems inconsistent with the agency theory since the optimal compensation contracts that provide incentives for managers to create shareholder wealth will not be independent of their shareholdings. Their study findings were based on the sampling of the 73 manufacturing firms for the 15 years period. Cyert, Kang, and Kumar (2002) also argued that the CEO pay is negatively related to the share ownership of the board‘s compensation committee; and doubling compensation committee ownership reduces non-salary compensation by 4-5 percent. In addition, many other studies also failed to find any relationship between the firm value and the executives‘ equity stakes (e.g., Agrawal & Knoeber 1996, Himmelberg et al. 1999, Demsetz & Villalonga 2001), primarily due to the equity holdings were the decision of the managers and the boards, none of these correlations can be interpreted as causal. However, these findings were challenged by Mehran (1995) who found a positive relation- ship between the percentage of total compensation in cash (salary and bonus) and the percentage of shares held by managers. This was supported by Jensen and Murphy (1990) found in their study that changes in both the CEO‘s pay-related wealth and the value of his stock holdings were positively and statistically related to the changes in the shareholder‘s wealth, and the CEO turnover probabilities were negatively and significantly related to changes in shareholder wealth. Ungson and Steers (1984) believed that in the firms where the CEO had large shareholdings, long tenure, control of the top management team, or other means, the CEO can largely shape his or her pay. Similarly, Finkelstein and Ham- brick (1988), believed that the relative power of the CEO may affect the height of the hurdles that are set to qualify for the con- tingent pay. In addition, they also believed that the executives who own the significant portions of their firms are likely to con- trol not only the operating decisions but the board decisions as well. As such, the executives would be in a position to essentially set their own compensation. In addition, they believed that the stronger the family‘s position in the firm, the stronger will be the executive‘s position, despite the family shareholders may not be as active as the independent directors might be. They also found that the CEO compensation and shareholdings are related in an inverted-U manner, with the compensation highest in situations of moderate the CEO ownership. That is, the point of inflection happened when the CEO shareholdings reached about the 9 per-

IJSER © 2012

The research paper published by IJSER journal is about The Importance of Firm Ownership on CEO Compensation: An Empirical Study on New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) Companies 5

ISSN 2229-5518

cent. Up to that point, increases in the CEO ownership seemed to bring increased salaries, due to increase in the CEO Power and the CEO Tenure for the first 18 years, and beyond that ownership level, the salaries dropped, due to tax preference of incurring the capital gains over the current income.

Jensen and Murphy (1989) found that the executive in- side-stock ownership can provide incentives, but these holdings are not generally controlled by the corporate board, and the ma- jority of the top executives have the small personal equity owner- ship. Bertrand and Mullainathan (2000) found that the CEOs in the firms that lacks a 5 percent (or larger) external shareholder tend to receive more luck-based pay − pay associated with the profit increases that are entirely generated by the external factors rather than by managers‘ efforts. They also found that in the firms lacking large external shareholders, the cash compensation of CEOs is reduced less when their option-based compensation is increased.

Murphy (1986) argued that the CEO tenure had shown

to influence the CEO performance pay in prior research. The in-

creased CEO tenure may promote a principal‘s trust of an agent and the assumption that actions will be taken in the principal‘s interest. Sigler (2011) argued that the CEO tenure appears to be one of the significant variables in determining the level of the CEO compensation. His examination was based on the 280 firms listed on the New York Stock Exchange for a period from 2006 to

2009.

personal circumstances influence pay. They also argued that the longer the CEO‘s tenure, the more the board will consist of his or her own, often sympathetic appointees. In addition, the man- agement-controlled firms where the CEOs were relatively power- ful, CEO tenure was likely to be important to pay determinants. Despite their detailed findings their study was inconclusive as they failed to derive strong expected correlations among the va- riables due to the small sample-sized sampling which had af- fected the results not being representative of the larger popula- tion. However, Pfeffer (1981) supported Finkelstein and Ham- brick (1989) findings and believed that the creation of a personal mystique which may induce unquestioned deference or loyalty, can be expected to occur when the CEO power becomes institu- tionalized in the organization. A second source of power that is expected to affect compensation is the executive‘s shareholdings in the firm.

Deckop (1988) argued that the CEO‘s age had little effect on the CEO compensation. However, Finkelstein and Hambrick (1998) found an inverted U-shaped relationship between the CEO age and the CEO cash compensation. The cash compensation increased with an age up to a point at 59 years, beyond which real cash earnings decreased. They also believed that this pattern of the earnings over-time is in line with the CEO‘s need for cash, which tends to drop off as he or she gets older due to no major expenditures to incur such as house and child-rearing expenses.

Finkelstein and Hambrick (1989) believed that the CEO tenure was thought to have a positive link with the compensa- tion, with pay steadily increasing as the CEO gains and solidifies the power over-time. However, in their findings such a pattern was not observed for any of the measures of the CEO compensa- tion. Since a monotonic relationship was not found between the CEO tenure and the CEO pay, the existence of a curvilinear asso- ciation was investigated. In addition, the average tenure of the CEOs was significantly lower in the externally-controlled firms (2.96 years) than the management-controlled firms (5.92 years). Thus, they believed that the boards of the externally-controlled firms may not need to pay from the profitability because the CEO tenure was dependent on the owner‘s satisfaction with the CEO performance. For the total pay, this finding was relatively strong with the inflation adjusted pay starting to decline at about 18 years of tenure. According to them there were two possible ex- planations for this curvilinear pattern. The first was that the pow- er accrues for a while and then diminishes due to the CEO‘s re- duced mobility in the managerial labor market, or due to his evo- lution into a figurehead with one or two younger high priced executives who carry the actual weight of the CEO‘s job. The second possibility was that executive reach a point where they prefer other forms of the compensation over the current cash. This could occur because of the changes in the family and the financial circumstances, or due to a switch to reliance on the stock appreciation and dividends, as the CEO‘s shareholdings increase over-time. This supposition was supported when the two sub- samples were examined (p < 0.01) greater shareholdings than a short-tenure low-pay group. Hence, it was not that long-tenured CEOs are paid less, but rather that the pay mix shifts from the cash to the stock earnings over-time, supporting the notion that

firm-specific wealth that a CEO owns. This finding was also sup-

ported by Tosi, Werner, Katz, and Gomez-Mejia (2000) and Dal-

ton et al. (2003) that there was a negligible relationship between

the CEO equity ownership and the organization performance. That is, there was a little evidence to support agency theory‘s emphasis on alignment of financial interests and of agent prefe- rences and actions through equity ownership.

This research had adopted the quantitative research method as it is the method to be used for the historical data collection and the descriptive studies. The longitudinal study approach had been selected under the quantitative research methodology to study the corporate financial records from 2005 to 2010. The random sampling method had been selected for this research to obtain the

IJSER © 2012

The research paper published by IJSER journal is about The Importance of Firm Ownership on CEO Compensation: An Empirical Study on New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) Companies 6

ISSN 2229-5518

total sampling population of the one hundred and twenty com- panies from the NYSE index.

For the statistical tests, the CEO Compensation was as- signed as the dependent variable; the Firm Size was assigned as the control variable and the independent variable; and the CEO Performance and the Corporate Governance had been assigned as independent variables. Each sub-variables of the CEO Com- pensation had been used separately to attest with all the sub- independent variables of the Firm Size, the Firm Performance, and the Corporate Governance. The total of the nine models were created and accordingly attest each of them to address the re- search question.

The survey method had been adopted as it is the most appropriate approach to collect the historical data. The historical data of the sampled companies had been obtained from the TMX Group Inc. and the CDS Inc. The Inferential statistics-based me- thodology, which is very instrumental in this quantitative re- search, had been used to obtain statistical results. The 95 percent confidence level will be assumed for all the research attestations.

Performance had a material impact on the CEO short-term com- pensation, in the Owner-Controlled companies. The third and the sixth models between the CEO Total Compensation, the Firm Size, and the Accounting Performance models were .638 and .935, as such, characterized also as strong ratios. Thus, these models indicated that the long-term CEO Compensation had been heavi- ly influenced by the Firm Size and the Accounting Performance, perhaps due to the design of the CEO contract for the long-term compensation, and also perhaps the management‘s intention of compensating CEO through stocks then cash bonus. The seventh, the eighth, and the ninth models between the CEO Salary, the CEO Bonus, the CEO Total Compensation, and the Corporate Governance were .291, .03, and .113 respectively, as such, charac- terized as weak to moderate ratios. Thus, these models indicated that the Corporate Governance factors were irrelevant towards determining the CEO Compensation in the Owner-Managed companies. Signifying, this was perhaps due to the weak influ- ence of the Corporate Governance betas towards the CEO Salary, the CEO Bonus, and the CEO Total Compensation.

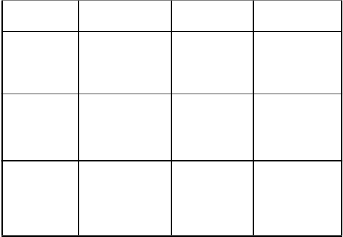

Table 2 (Regression Analysis - ANOVA)

Table 1 (Regression Analysis – ANOVA)

Owner-

Salary Bonus

Managed

Total

Compensation

Firm Size

Firm

Performance

Corporate

Governance

F(2,517)=114.866 F(2,482)=7.481 F(2,534)=470.366

p=.000 p=.001 p=.000

R2=0.285 R2=0.03 R2=0.638

F(8,97)=17.777 F(8,94)=43.658 F(8,92)=165.798 p=.000 p=.000 p=.000

R2=0.595 R2=0.788 R2=0.935

F(7,582)=17.882 F(7,470)=2.061 F(7,542)=9.904

The above ANOVA table 2 results were based on the linear re- gression testing. It showed that there was a relationship between the CEO Salary, the CEO Bonus, the Total Compensation, the

in the Management-Owned companies. The first, the second, and the third models between the CEO Salary, CEO Bonus, the CEO Total Compensation, and the Firm Size were .451, .584, and .712 respectively, as such characterized as good to strong ratios. Thus,

The above ANOVA table 1 results were based on the linear re-

gression testing. It showed that there was a relationship between the CEO Salary, the CEO Bonus, the Total Compensation, the Firm Size, the Firm Performance, and the Corporate Governance, in the Owner-Managed companies. The first and the second models between the CEO Salary, CEO Bonus, and the Firm Size were .285 and .03 respectively, as such characterized as weak ra- tios. Thus, these models indicated that in the Owner-Managed companies, the Firm Size had a weak impact on the CEO short- term compensation. The fourth and the fifth models between the CEO Salary, the CEO Bonus, and the Accounting Performance were .595 and .788 respectively, as such characterized as weak to strong ratios. Thus, these models indicated that the Accounting

these models indicated that in the Management-Owned compa- nies, the Firm Size had a material impact on the CEO Compensa- tion System. The fourth, the fifth, the seventh, and the eight mod- els between the CEO Salary, the CEO Bonus, the Accounting Per- formance, and the Corporate Governance were .279, .041, .291, and .334 respectively, as such characterized as weak to moderate ratios. Thus, these models indicated that in the Management- Owned companies, the Accounting Performance and the Corpo- rate Governance models were not the relevant influential factors in determining the CEO short-term compensation. Signifying, this was perhaps due to weak influence of bonus betas of the Ac- counting Performance and the Corporate Governance. The sixth and the ninth models between the CEO Total Compensation, the

IJSER © 2012

The research paper published by IJSER journal is about The Importance of Firm Ownership on CEO Compensation: An Empirical Study on New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) Companies 7

ISSN 2229-5518

Firm Performance, and the Corporate Governance were .632 and

.571 respectively, as such characterized as strong ratios. Thus,

these models indicated that the Firm Performance and the Corpo-

rate Governance factors had influenced the long-term benefits

components of the CEO Total Compensation in the Management-

Controlled companies. In addition, it also signified that the CEO

contract had been heavily weighted towards the long-term CEO

compensation.

Table 3 – Correlations (CEO Compensation vs. Firm Size)

Owner-Managed | Salary | Bonus | Total Compensation |

Total Sales | 0.488 | -0.161 | 0.618 |

Total Employees | 0.441 | -0.146 | 0.76 |

The above table 3 illustrated the correlation results between the three categories of the CEO Compensation and the Firm Size in the Owner-Managed companies. It showed that there was a strong correlation existed between the CEO Salary, the Total Compensation, the Total Sales, and the Total Employees. On the other hand, the CEO Bonus had negative correlation with the Total Sales and the Total Employees. Thus, it signifies that in the NYSE Owner-Managed companies, the CEO Salary and the long- term benefits are highly correlated to the Firm Size. The relation- ships between the CEO Salary, the Total Sales, and the Total Em- ployees were .488 and .441 respectively which indicated that the Total Sales and the Total Employees were influential factor in determining the CEO Salary. However, the relationships between the CEO Bonus, the Total Sales, and the Total Employees were -

.161 and -.146 respectively which indicated that the level of the Total Sales and the Total Employees had a negative influence in determining the CEO Bonus. That is, CEO Bonus was not deter- mined on the basis of the firm size. Likewise, the relationship between the CEO Total Compensation, the Total Sales, and the Total Employees were .618 and .76 respectively which also indi- cated that the level of the Total Sales and the Total Employees were strong influential factor in determining the CEO Total Compensation. In addition, it showed that the cash and non-cash components of the CEO compensation were equally influenced by the variables of the Firm Size.

Table 4 – Correlations (CEO Compensation vs. Firm Size)

were .635 and .518 respectively which indicated that the Total Sales and the Total Employees were influential factor in deter- mining the CEO Salary. However, the relationships between the CEO Bonus, the Total Sales, and the Total Employees were .183 and -.098 respectively which indicated that the level of the Total Sales and the Total Employees had a weak negative to weak posi- tive influence in determining the CEO Bonus. Likewise, the rela- tionships between the CEO Total Compensation, the Total Sales, and the Total Employees were .686 and .513 respectively which also indicated that the level of the Total Sales and the Total Em- ployees were strong influential factor in determining the CEO Total Compensation. In addition, similar to above, it showed that the cash and non-cash components of the CEO compensation were equally influenced by the variables of the Firm Size.

Overall, it was found that the Firm Size had a similar effect to the CEO Compensation, both under Owner-Managed and Management-Controlled companies. That is, in both types of ownerships, the CEO Salary and the long-term benefits had a strong influence towards the CEO Compensation. Similarly, the CEO Bonus had a weak effect towards the CEO Compensation, signifying that the Firm Size had either weak positive or weak negative impact on the CEO Bonus. That is, the CEO Bonus was determined on the criteria other than the Firm Size, perhaps may find the true linkages in the coming sections.

Table 5 – Correlations (CEO Compensation vs. Firm Performance)

Management-Controlled | Salary | Bonus | Total Compensation |

Total Sales | 0.635 | 0.183 | 0.686 |

Total Employees | 0.518 | -0.098 | 0.513 |

![]()

![]()

The above table 4 illustrated the correlation results between the three categories of the CEO Compensation and the Firm Size. It showed that there was a strong correlation existed between the CEO Salary, the Total Compensation, the Total Sales, and the Total Employees. On the other hand, the CEO Bonus had weak negative to moderate relationship with the Total Sales and the Total Employees. Thus, it signifies that in the NYSE Manage- ment-Controlled companies, the CEO Salary and the long-term benefits are highly correlated to the Firm Size. The relationships between the CEO Salary, the Total Sales, and the Total Employees![]()

The above table 5 illustrated the correlation results between the sub- variables of the CEO Compensation and the sub-variables of the Firm Performance both under Owner-Managed and Management-

IJSER © 2012

The research paper published by IJSER journal is about The Importance of Firm Ownership on CEO Compensation: An Empirical Study on New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) Companies 8

ISSN 2229-5518

Controlled scenarios. In the Owner-Managed and the Management- Controlled companies, it showed that there were weak positive corre- lations existed between the CEO Salary, the CEO Bonus, the CEO Total Compensation, the Return on Assets (ROA), and the Return on Equity (ROE). That is, the correlations were, .16, .12, .038, .35, .179,

.011, .076, -.26, .224, .178, .06, and .054 respectively. Thus, in both types of ownerships, these balance sheet related items had nil to neg- ligible impact towards the determination of the CEO Compensation, perhaps the board did not consider these sub-variables as true per- formance criteria of the CEO effort.

In the Owner-Managed companies, it was found that there were strong correlations existed between the CEO Salary, the CEO Bonus, the CEO Total Compensation, the Earnings per Share, the Cash Flow per Share, the Net Profit Margin, the Common Share Out- standing, the Book Value per Common Share Outstanding, and the Market Value per Common Share Outstanding. That is, the correla- tions were, .353, .607, .359, .705, .03, .714, .230, .429, .543, .748, .088,

.847, .398, .746, .553, .796, .061, and .948. Thus, in the Owner-Managed companies, the CEO Compensation for both the short-term and the long-term were influenced by the net-earnings related items and the market performance activities.

In contrary, in the Management-Controlled companies, it

was found that there was a weak correlation between the CEO Sal- ary, the Earnings per Share, the Cash Flow per Share, the Net Profit Margin, the Common Share Outstanding, and the Book Value per Common Share Outstanding, exception to the Market Value per Common Share Outstanding which was characterized as good ratio. That is, the correlations were, .106, -.016, .178, .074, .252, and .500. Thus, these weak results in the Management-Controlled companies were perhaps due to being the CEOs contracts were more weighted towards the management of the organization rather than quantitative financial criteria.

In the area of the CEO Bonus, contrary to the findings of the Owner-Managed companies, it was found that in the Management- Controlled companies, the relationship between the CEO Bonus, the Earnings per Share, the Cash Flow per Share, the Net Profit Margin, the Common Share Outstanding, the Book Value per Common Share Outstanding, and the Market Value per Common Share Outstanding was characterized as weak negative. That is, the correlations were

.032, -.054, -.027, -.105, -.089, and -.147. Thus, in the Management- Controlled companies, the CEO Bonus was also not rewarded on the basis of Firm Performance signifying that perhaps the CEOs were rewarded more with the achievement of the qualitative criteria such as organizational management and strategic goals. In the Manage- ment-Controlled companies, the relationships between the CEO Total Compensation, the Earnings per Share, the Cash Flow per Share, the Net Profit Margin, the Common Share Outstanding, the Book Value per Common Share Outstanding, and the Market Value per Com- mon Share Outstanding were ranged from weak negative to strong positive ratios. That is, the correlations were, .07, -.007, .386, .218, .356, and .751. Thus, it showed that overall, in the Management-Controlled companies, the long-term benefits had moderately influenced by these sub-variables of the Accounting Performance. Relatively, these results were in contrary to the strong positive findings observed in the Owner-Managed companies. Overall, in the Management- Controlled companies, the CEO contracts in general were designed to assess the CEO skills and the minimization of the financial firm per- formance risk borne to the CEO.

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE | Sa la ry | Bonus | Tota l Compe ns a tion | |||

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE | Owne r- Contr. | Mgmt.- Contr. | Owne r- Contr. | Mgmt.- Contr. | Owne r- Contr. | Mgmt.- Contr. |

CEO Age | 0.08 | 0.136 | -0.094 | -0.219 | 0.02 | -0.053 |

CEO Sha re s Outs ta nding | -0.035 | 0.031 | -0.085 | -0.376 | -0.009 | 0.052 |

CEO Sha re Va lue | 0.049 | 0.418 | -0.081 | -0.264 | 0.112 | 0.566 |

CEO Te nure | -0.06 | 0.156 | -0.064 | -0.202 | -0.058 | 0.136 |

CEO Turnove r | -0.119 | 0.05 | 0.088 | 0.293 | -0.041 | 0.119 |

MGMT. 5% Owne rs hip | -0.334 | -0.084 | 0.055 | -0.103 | 0.254 | -0.186 |

I NDV./I NST. 5% Owne rs hip | -0.262 | 0.293 | 0.036 | 0.198 | -0.192 | 0.306 |

The above table 6 illustrated the correlation results between the sub- variables of the CEO Compensation and the sub-variables of the Corporate Governance both under Owner-Managed and Manage- ment-Controlled scenarios. In the Owner-Managed companies, it showed that there was a weak to moderate negative correlations ex- isted between the CEO Salary, the CEO Age, the CEO Shares Out- standing, the CEO Share Value, the CEO Tenure, the CEO Turnover, the 5 percent Management Ownership, and the 5 percent Individu- als/Institutions Ownership. That is, in the Owner-Managed compa- nies, the correlations between the CEO Salary and the Corporate Governance factors were .080, -.035, .049, -.06, -.119, -.334, and -.262, respectively. Thus, it showed that overall the Corporate Governance factors had no influence towards the determinant of the CEO Salary signifying the CEO had no influence towards the Board in his Salary determination, despite the shares ownership as expected criteria. However, in the Management-Controlled companies, it showed that there was a weak to moderate positive correlations existed between the CEO Salary, the CEO Age, the CEO Shares Outstanding, the CEO Share Value, the CEO Tenure, the CEO Turnover, the 5 percent Man- agement Ownership, and the 5 percent Individuals/Institutions Ownership. That is, the correlations between the CEO Salary and the Corporate Governance factors were .136, .031, .418, .156, .05, .084, and

.293, respectively. Thus, it showed that the CEO had some degree of influence over the Board towards his Salary determination, in par- ticular through the performance criteria of the market price of the share and the duration of the service.

In the Owner-Managed companies, it showed that there

was a weak negative to weak positive correlations existed between the CEO Bonus, the CEO Age, the CEO Shares Outstanding, the CEO Share Value, the CEO Tenure, the CEO Turnover, the 5 percent Man-

IJSER © 2012

The research paper published by IJSER journal is about The Importance of Firm Ownership on CEO Compensation: An Empirical Study on New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) Companies 9

ISSN 2229-5518

agement Ownership, and the 5 percent Individuals/Institutions Ownership. That is, in the Owner-Managed companies, the correla- tions between the CEO Bonus and the Corporate Governance factors were -.094, -.085, -.081, -.064, .088, .055, and .036, respectively. Thus, it showed that the CEO Age, the CEO Shares Outstanding, the CEO Share Value, and the CEO Tenure, had negligible impact on the CEO Bonus; however, the CEO Turnover, the Management 5 percent Ownership, and the 5 percent Individuals/Institutions Ownership had a weak influence on the CEO Bonus. Overall, the CEOs lacked strong influence over the Board towards his CEO Bonus determina- tion in the Owner-Managed companies. In contrary, in the Manage- ment-Controlled companies, it was found that there was a weak to moderate negative correlations between them. That is, the correla- tions were -.219, -.376, -.264, -.202, .293, -.103, and .198, respectively. Thus, it showed that, in the Management-Controlled companies, the CEO contract completely ignored the Corporate Governance factors, and also Board perhaps had a negative perception towards the Cor- porate Governance factors, towards determining the CEO Bonus.

In the Owner-Managed companies, it showed that there was a weak

negative to weak positive correlations existed between the CEO Total Compensation, the CEO Age, the CEO Shares Outstanding, the CEO Share Value, the CEO Tenure, the CEO Turnover, the 5 percent Man- agement Ownership, and the 5 percent Individuals/Institutions Ownership. That is, in the Owner-Managed companies, the correla- tions between the CEO Total Compensation and the Corporate Gov- ernance factors were .02, -.009, .112, -.058, -.041, .254, and -.192, re- spectively. Thus, it showed that in the Owner-Managed companies, the long-term benefits had not been influenced by the Corporate Governance factors, similar to the CEO Salary and the CEO Bonus. However, in the Management-Controlled companies, the long-term benefits had a positive impact on the Corporate Governance factors. That is, in the Management-Controlled companies, the correlations between the CEO Total Compensation and the Corporate Govern- ance factors were -.053, .052, .566, .136, .119, -.186, and .306, respec- tively. Overall, the Corporate Governance had a weak influence on the CEO Compensation in both the Owner-Managed and the Man- agement-Controlled scenarios, perhaps due to the strong influence of the Firm Size and the Accounting Firm Performance as primary crite- ria towards determining the CEO Compensation.

Overall, in both the Owner-Managed and the Management- Controlled companies, it was found that there was a relationship existed between the CEO Salary, the CEO Bonus, the CEO Total Compensation, the Firm Size, the Accounting Firm Performance, and the Corporate Governance.

In the area of the Firm Size, in both the Owner-Managed and

the Management-Controlled scenarios, the Firm Size had a strong

influence towards the CEO Salary and the long-term benefits. On

the other hand, the Firm Size had a negative impact on the CEO

Bonus.

In the area of Accounting Performance, in the Owner-

Managed and the Management-Controlled companies, it showed

that there were weak positive correlations existed between the

CEO Salary, the CEO Bonus, the CEO Total Compensation, the

Return on Assets, and the Return on Equity. In the Owner-

Managed companies, it was found that there were strong correla- tions existed between the CEO Salary, the CEO Bonus, the CEO Total Compensation, the Earnings per Share, the Cash Flow per

Share, the Net Profit Margin, the Common Share Outstanding, the Book Value per Common Share Outstanding, and the Market Value per Common Share Outstanding. In contrary, in the Man- agement-Controlled companies, it was found that there was a weak correlation between the CEO Salary, the Earnings per

Share, the Cash Flow per Share, the Net Profit Margin, the Com- mon Share Outstanding, and the Book Value per Common Share Outstanding, exception to the Market Value per Common Share Outstanding which was characterized as good ratio. Similarly, in contrary to the findings of the Owner-Managed companies, it was found that in the Management-Controlled companies, the relationship between the CEO Bonus, the Earnings per Share, the Cash Flow per Share, the Net Profit Margin, the Common Share Outstanding, the Book Value per Common Share Outstanding,

and the Market Value per Common Share Outstanding was char-

acterized as weak negative. In the Management-Controlled com-

panies, the relationships between the CEO Total Compensation, the Earnings per Share, the Cash Flow per Share, the Net Profit Margin, the Common Share Outstanding, the Book Value per Common Share Outstanding, and the Market Value per Common Share Outstanding were ranged from weak negative to strong positive ratios.

In the area of the Corporate Governance, in the the Owner- Managed companies, it showed that there was a weak to moder- ate negative correlations existed between the CEO Salary, the CEO Age, the CEO Shares Outstanding, the CEO Share Value, the CEO Tenure, the CEO Turnover, the 5 percent Management Ownership, and the 5 percent Individuals/Institutions Owner- ship. However, in the Management-Controlled companies, it showed that there was a weak to moderate positive correlations existed between the CEO Salary, the CEO Age, the CEO Shares Outstanding, the CEO Share Value, the CEO Tenure, the CEO Turnover, the 5 percent Management Ownership, and the 5 per-

cent Individuals/Institutions Ownership. In the Owner-Managed companies, it showed that there was a weak negative to weak positive correlations existed between the CEO Bonus, the CEO Age, the CEO Shares Outstanding, the CEO Share Value, the

CEO Tenure, the CEO Turnover, the 5 percent Management Ownership, and the 5 percent Individuals/Institutions Owner- ship. In contrary, in the Management-Controlled companies, it was found that there was a weak to moderate negative correla- tions between them. In the Owner-Managed companies, it showed that there was a weak negative to weak positive correla- tions existed between the CEO Total Compensation, the CEO Age, the CEO Shares Outstanding, the CEO Share Value, the CEO Tenure, the CEO Turnover, the 5 percent Management Ownership, and the 5 percent Individuals/Institutions Owner- ship. However, in the Management-Controlled companies, the long-term benefits had a positive impact on the Corporate Gov- ernance factors.

1. Agrawal A, and Knoeber, C.R. (1996), ‗Firm perfor-

mance and mechanisms to control agency problems be- tween managers and shareholders‘, Journal of Finance Quantitative Analysis, Vol. 31(3), pp. 377-397.

IJSER © 2012

The research paper published by IJSER journal is about The Importance of Firm Ownership on CEO Compensation: An Empirical Study on New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) Companies 10

ISSN 2229-5518

2. Allen, M.P. (1974), ‗The Structure of inter-organizational elite co-optation‘, American Sociological Review, Vol. 39, pp. 393-406.

3. Amould, Richard J. (1985), ‗Agency costs in Banking Firms: An Analysis of Expense Preference Behaviour‘, Journal of Economics and Business, Vol. 37, pp. 103-112.

4. Antle, Rick, and Smith, Abbie (1986), ―An Empirical In-

vestigation of the Relative Performance Evaluation of

Corporate Executives‖, Journal of Accounting Research,

Vol. 24, No. 1 (Spring), pp. 1-39.

5. Belkaoui, A., and Picur, R. (1993), ‗An analysis of the use

of accounting and market measures of performance, CEO experience and nature of deviation from analyst forecasts‘, Managerial Finance, Vol. 19(2), pp. 33-54.

6. Bertrand, Marianno and Mullainathan, Sendhil (2001),

‗Are CEO‘s Rewarded for Luck? The Ones Without

Principals Are‘, Quarterly Journal of Economics, pp. 901-

932.

7. Blanchard, Olivier Jean, Lopez-de-Selanes, Florencio,

and Shleifer, Andrei (1994), ‗What do Firms do with Cash indfalls?‘, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 36 (3), pp. 337-360.

8. Borman, W. C., & Motowidlo, S. J. (1993), ‗Expanding the criterion domain to include elements of contextual performance‘, in N. Schmitt & W. C. Borman

(Eds.), Personnel selection in organizations, pp. 71-98, San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

9. Boyd, Brian K. (1994), ‗Board Control and CEO Com-

pensation‘, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 15, pp.

335-344.

10. Carpenter, M. A., & Sanders, W. M. G. (2002), ‗Top man-

agement team compensation: The missing link between

CEO pay and firm performance‘ Strategic Management

Journal, 23, pp. 367-375.

11. Coughan, Anne T., and Schmidt, Ronald M. (1985), ―Ex-

ecutive Compensation, Management Turnover, and

Firm Performance: an Empirical Investigation‖, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 7, Nos. 1-3 (April), pp. 43-66.

12. Cyert, Richard, Sok-Hyon, Kang, and Praveen Kumar

(2002), ‗Corporate Governance, Take-overs, and Top-

Management Compensation: Theory and Evidence,‘

Management Science, Vol. 48 (4), pp. 453-469.

13. David, P., Kochar, R., and Levitas, E. (1998), ‗The effect of institutional investors on the level and mix of CEO compensation‘, Academy of Managerial Journal, Vol. 41, pp. 200-228.

14. Deckop, John R. (1988), ―Determinants of Chief Execu-

tive Officer Compensation‖, Industrial and Labor Rela- tions Review, Vol. 41, No. 2, pp. 215-226.

15. Demsetz, H. and Villalonga, B. (2001), ‗Ownership struc-

ture and corporate performance‘, Journal of Corporate

Finance, Vol. 7(3), pp. 209-233.

16. Dyl, Edwardn A. (1998), ‗Corporate control and man- agement compensation‘, Managerial and Decision Eco- nomics, vol. 9, pp. 21-25.

17. Finkelstein, S. & Boyd, B. K. (1998), ‗How much does CEO matter? The role of managerial discretion in the set- ting of CEO compensation‘, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 41, pp. 179-199.

18. Finkelstein S. and Hambrick, D. (1989), ‗Chief executive

compensation: A Study of the intersection of markets

and political processes‘, Strategic Management Journal,

Vol 10, Issue 2, pp. 121-134.

19. Finkelstein S. and Hambrick, D. (1996), Strategic Leader-

ship: Top Executive and their Effects on Organization.

West Publishing: New York.

20. Fox, Hartland (1983), ‗Top Executive Compensation,

Conference Board publication.

21. Gibbons, Robert, and Murphy, Kevin J. (1990), ―Relative Performance Evaluation for Chief Executive Officers‖, Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 43, No. 3, pp. 30S-51S.

22. Gomez-Mejia, Luis R. and Tosi, Henry L., Hinkin, T.

(1987), ‗Managerial control, performance, and executive compensation‘, Academy of Management Journal, Vol.

30, pp. 51-70.

23. Gomez-Mejia, Luis R. and Barkema, Harry G. (1998),

‗Managerial Compensation and Firm Performance: A General Research Framework‘ The Academy of Man- agement Journal, Vol. 2, No. 2, Special Research Forum on Managerial Compensation and Firm Performance, pp. 135-145.

24. Gomez-Mejia, Luis R. and Tosi, Henry L. (1989), ‗The Decoupling of CEO Pay and Performance: An Agency Theory Perspective‘, Administrative Science Quarterly,

34, pp. 169-189.

25. Gomez-Mejia, Luis R. and Tosi, Henry L. (1994), ‗CEO

Compensation Monitoring and Firm Performance‘, The

Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 37, No. 4 (Aug.

1994), pp. 1002-1016.

26. Gray, S. R., & Cannella, A. A. (1997), ―The Role of Risk in

Executive Compensation‖, Journal of Management, Vol.

23, pp. 517-540.

27. Hambrick, D.C. and Finkelstein, S. (1995), ‗The Effects of

Ownership Structure on Conditions at the Top: The Case

of CEO Pay Raises‘, Strategic Management Journal, Vol.

16, pp. 175-194.

28. Himmelberg CP, Hubbard RG, and Palia D. (1999), ‗Un-

derstanding the determinants of managerial ownership and the link between ownership and performance‘, Journal of Finance Economics, Vol.. 53(3), pp. 353-384.

29. Iyengar, Raghavan J. (2000), ‗CEO Compensation In Poorly Performing Firms‘, Journal of Applied Business Research, Vol. 16, Issue 3, pp.1-28.

30. Jensen M., and Murphy, K. (1985), ―Management Com-

pensation And The Managerial Labor Market‖, Journal

of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 7, No. 1-3, pp. 3-9.

31. Jensen M., and Murphy, K. (1990), ‗Performance pay and top management incentives‘, Journal of Political Econo- my, Vol. 98, pp. 225-264.

IJSER © 2012

The research paper published by IJSER journal is about The Importance of Firm Ownership on CEO Compensation: An Empirical Study on New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) Companies 11

ISSN 2229-5518

32. Jensen M., and Murphy, K. (1990b), ‗CEO Incentives: It‘s not how much you pay but how‘, Harvard Business Re- view, Vol. 68, No. 3, pp. 138-153.

33. Jensen M., and Murphy, K. (2010), ‗CEO incentives – It‘s

not how much pay, but how‘, Journal of Applied Corpo- rate Finance, Vol. 22, pp. 64-76.

34. Jensen, Michael C., and Meckling, William H. (1976),

‗Theory of the firm: Managerial behaviour, agency costs and ownership structure, Journal of Financial Econom- ics, Vol. 3, pp. 305-360.

35. Jensen, Michael C., and Ruback, Richard S. (1983), ‗The

market for corporate control‘, Journal of Financial Eco- nomics, Vol. 11, pp. 5-50.

36. Jensen, Michael C. and Zimmerman, Jerold L. (1985),

―Management Compensation And The Managerial Lbor Market‖, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 7, No. 1-3, pp. 3-9.

37. Joskow, Paul L., and Nancy, L. (1994) ‗CEO Pay and

Firm Performance: Dynamics, Asymmetries, and Alter-

native Performance Measures‘, NBER Working Paper

Series, vol. w 4976.

38. Kostiuk, Peter F. (1990), ‗Firm Size and Executive Com-

pensation‘, The Journal of Human Resources, University

of Wisconsin Press, Vol. 25, pp. 90-105.

39. Lambert, R. and Larker, D. (1984), ‗Stock Options and Marginal Incentives‘, Working Paper, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL.

40. McEachern, W. (1975), Managerial control and perfor-

mance. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

41. Mehran, H. (1992), ‗Executive Incentive Plans, Corporate Control, and Capital Structure‘, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, Col. 27, pp. 539-560.

42. Mehran, H. (1995), ‗Executive compensation structure,

ownership, and firm performance‘ Journal of Financial

Economics, Vol. 38: 163-184.

43. Murphy, Kevin J. (1985), ‗Corporate performance and managerial remuneration, Journal of Accounting and Statistics, Vol. 7, pp. 11-42.

44. Murphy, K. J. (1986), ‗Incentives, learning and compen-

sation: A theoretical and empirical investigation of ma-

nagerial labor contracts‘, Rand Journal of Economics,

Vol. 7, pp. 105-131.

45. Murphy, Kevin J. (1999), ‗Executive Compensation‘, Handbook of Labor Economics, Vol. III, Amsterdam: North-Holland, pp. 2485-2563.

46. Murphy K. J. and Gibbons, R. (1989), ‗Optimal Incentive

Contracts in the Presence of Career Concerns: Theory

and Evidence‘, pp. 90-109.

47. Murphy, K. J., and Oyer, P. (2002), Discretion in execu- tive incentive contracts: Theory and evidence, Working paper, University of Southern California and Stanford University.

48. Murphy, K. R. and Slater, M. (1975), ‗Should CEO pay be linked to results?‘, Harvard Business Review, vol. 53(3), pp. 66-73.

49. Pfeffer, Jeffrey (1981), ‗Managing with Power‘, Pitman

Publication.

IJSER © 2012

50. Prasad, S. B. (1974), ‗Top Management Compensation and Corporate Performance‘, The Academy of Man- agement Journal, Vol. 17, pp. 554-558.

51. Sigler, K. J. (2011), ‗CEO Compensation and Company

Performance‘, Business and Economic Journal, Volume

2011, pp. 1-8.

52. Sanders, W. G., and Carpenter, M.A. (1998) ‗Internatio- nalization and firm governance: The roles of CEO com- pensation, top team composition , and board structure‘, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 41, pp. 158-178.

53. Sigler, K. J. (2011), ‗CEO Compensation and Company

Performance‘, Business and Economic Journal, Volume

2011, pp. 1-8.

54. Simmons, S. A., M. Kroll, and P. Wright (1991), ‗Winners and Losers in Acquisitions: A Cononical Correlation Analysis‘, Southeastern Division of The Institute of Management Sciences Meeting.

55. Sloan, R. (1993), ‗Accounting Earnings and Top Execu-

tive Compensation‘, Journal of Accounting and Econom-

ics, Vol. 16, pp. 55-100.

56. Tosi H. L., Werner S., Katz J., Gomeiz-Mejia L. R. (1998),

‗A Meta-Analysis of Executive Compensation Stu-

dies,‘ unpublished manuscript, University of Florida at

Gainesville, pp. 58.

57. Tosi H. L., Werner S. Katz J., Gomeiz-Mejia L. R. (2000),

‗How Much Does Performance Matter? A Meta-Analysis

of CEO Pay Studies‘, Journal of Management, Vol. 26,

pp. 301-339.

58. Ungson, Gerardo R., and Richard M. Steers (1984), ‗Mo-

tivation and politics in executive compensation‘, Acad-

emy of Management Review, Vol. 9, pp. 313-323.

59. Werner, Steve,and Tosi, Henry, ―Other People‘s Money: The Effect of Ownership on Compensation Strategy and Managerial Pay‖, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 38, 1995, pp. 1672-1691.

H0: There is no relationship between, the CEO Compensation, the Firm Size, the Accounting Firm Performance, and the Corporate Govern- ance, in the NYSE companies.

H1: There is a relationship between, the CEO Com-

pensation, the Firm Size, the Accounting Firm Performance, and the Corporate Governance, in the NYSE companies.

To address this Operational Hypothesis Statement, the separate model was developed for each dependent vari- able:

For Salary: Y1=c+ B1X1+B2X2+ϵ

For Bonus: Y2=c+ B1X1+B2X2+ϵ

(Y1=Salary; Y2=Bonus; c=constant predictor;

http://www.ijser.org

The research paper published by IJSER journal is about The Importance of Firm Ownership on CEO Compensation: An Empirical Study on New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) Companies 12

ISSN 2229-5518

B1=influential factor for the Total Sales; B2=influential

factor for the Total Number of Employees; and ϵ =error).

(X1=Value of the Total Sales; X2=Value of the Total

Number of Employees).

For Salary: Y3=c+

B1X1+B2X2+B3X3+B4X4+B5X5+B6X6+B7X7+B8X8 +ϵ

For Bonus: Y4=c+

B1X1+B2X2+B3X3+B4X4+B5X5+B6X6+B7X7+B8X8+ϵ

(Y1=Salary; Y2=Bonus; c=constant predictor;

B1=influential factor for ROA; B2=influential factor for

ROE; B3=influential factor for EPS; B4=influential factor for CFPS; B5=influential factor for NPM; B6=influential factor for CSO; B7=influential factor for BVCSO;

B8=influential factor for MVCSO; and ϵ =error)

Let X1=Value of ROA; X2=Value of ROE; X3=Value of

EPS; X4=Value of CFPS; X5=Value of NPM; X6=Value of

CSO; X7=Value of BVCSO; B8=Value of MVCSO

For Salary: Y5=c+

B1X1+B2X2+B3X3+B4X4+B5X5+B6X6+B7X7+ϵ

For Bonus: Y6=c+

B1X1+B2X2+B3X3+B4X4+B5X5+B6X6+B7X7+ϵ

(Y5=Salary; Y6=Bonus; c=constant predictor;

B1=influential factor for the CEO Age; B2=influential

factor for the CEO Shares Outstanding; B3=influential

factor for CEO Shares Value; B4=influential factor for

CEO Tenure; B5=influential factor for CEO Turnover;

B6=influential factor for the Management 5 percent

Shares Ownership; B7= Individuals/Institutions 5 per-

cent Ownership; and ϵ =error).

Let X1=Value of CEO Age; X2=Value of CEO Shares

Outstanding; X3=Value of CEO Shares Value; X4=Value

of CEO Tenure; X5=Value of CEO Turnover; X6=Value of Management 5 percent Shares Ownership; and X7=Value of Individuals/Institutions 5 percent Owner- ship.

All the six models assumed to have a confidence level

(α) of 5 percent.

IJSER © 2012