International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 11, November-2013 123

ISSN 2229-5518

ABSTRACT

This research paper comprises of primary and secondary data. It investigates weakness and strengthens of educational institutions in Somalia. The primary purpose of the paper is to give information practitioners of education particularly those in Somalia to improve the quality of education; and to know how suppliers of education in Somalia apply TQM in education in their institutions. Total Quality management is a business approach designed for customer satisfaction and this paper examines how education suppliers in Somalia satisfied the requirement of their customers. Interviews with teachers, students, school principals and administrators of universities and also some parents and searched

websites and other educational sources that could be found education data of Somalia all indicate the need for application TQM approach in educational institutions in Somalia. Although this report was academic research but includes important references and information about Somalia education that would be useful for the scholars and supporters of education.

![]()

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 11, November-2013 124

ISSN 2229-5518

Whenever goods or services are produced, the organizations or institutions that supply them endeavor to satisfy requirements of customers and achieve specific goal of their own. Some organizations or institutions fail before they accomplish the end target of their activities. This is because their product is different from the real desires of customers and their supplies are lacking the principles of quality management. Researches and experiments conducted show that organizations and institutions that focus on both suppliers and customers are more profitable than those consider only to supply customers what they designed themselves without consultation the customers. In modern management approaches such as total quality

management, the organization is both customer and supplier. This concept supports effectual and effective tasks in which all are involved and participated in decisions of designing and developing product before presented to the end users.

Education is a service that governmental and non-governmental

entities provide to the people to

produce result that will benefit to the society wide. So, education institutions should change management practices and teaching methodologies that have proved unsuccessful and apply to new inventions. This provision of service (education) needs quality process (teachers and students) to produce quality supply to satisfy end

users/customers (parents and community as whole).

In this paper I want to discuss total

quality management (TQM) and why this business management approach is very important to apply education. Then, I will evaluate the quality of educational institutions in Somali. The paper will present current situation of schools and universities in Somalia.

It is not easy to give the word

“quality” specific definition that cannot be changed because what someone knows quality is another person’s poor. But there are accepted standards to measure quality. For example, if we want to know the quality of learning center, we look at teacher qualification, enrolment data, dropout data, site tidy and safety of school ground, pedagogy, inclusiveness and teacher-student interaction, etc.

Edward Sallis says that there are four quality imperatives in education (the moral imperative, the professional imperative, the competitive

imperative and accountability imperative) and the 3rd edition of Edward Sallis explains the thought as follows:

“The moral imperative-The customers and clients of the education service (students, parents and the community) deserve the best possible quality of education. This is the moral high ground in education and one of the few areas of educational discussion where there is

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 11, November-2013 125

ISSN 2229-5518

little dissent. It is the duty of educational professionals and administrators to have an overriding concern to provide the very best possible educational opportunities. The professional imperative- Closely linked to the moral imperative is the professional imperative. Professionalism implies a

commitment to the needs of students and an obligation to meet their needs by employing the most appropriate pedagogic practices. Educators have a professional duty to improve the quality of education and this, of course, places a considerable burden on teachers and administrators to ensure that both classroom practice and the management of the institution are operating to the highest possible standards.

lead to staff redundancies and

ultimately the viability of the institution can be under threat. Educationalists can meet the challenge of

competition by working to improve

the quality of their service and of their curriculum delivery mechanisms. The importance of TQM to survival is that it is a customer-driven process, focusing on the needs of clients and providing mechanisms to respond to their needs and wants.

Competition requires strategies that clearly differentiate institutions from

their competitors. Quality may

sometimes be the only differentiating factor for an institution. Focusing on the needs of the customer, which is at the heart of quality, is one of the

most effective means of facing the competition and surviving.

Schools and colleges are part of their communities and as such they must meet the political demands for education to be more accountable and publicly demonstrate the high standards. TQM supports the accountability imperative by promoting objective and measurable outcomes of the educational process and provides mechanisms for quality improvement. Quality improvement becomes increasingly important as institutions achieve greater control over their own affairs. Greater freedom has to be matched by greater accountability. Institutions have to demonstrate that they are able to deliver what is required of them. Failure to meet even one of these imperatives can jeopardize institutional well-being and survival. If institutions fail to provide the best

services they risk losing students who will opt for one of their competitors.

By regarding these drivers as anything less than imperatives we

risk the integrity of our profession and the future of our institutions. We are

in an era where parents and politicians are asking tough and

uncompromising questions. For education as for industry, quality

improvement is no longer an option, it is a necessity”1.

![]()

1 Edward Sallis, Total Quality Management in

Education, Third edition, Pages 3 and 4

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 11, November-2013 126

ISSN 2229-5518

A business management theory developed by Japanese in 1940’s and 1950’s but later modified by Americans (Feigenbum, Juran and Deming) who set foundation of TQM. (Mark Loughlin -2 0 0 8) says that “the evolution of TQM happened in a few stages easily identified as Inspection, Quality Control, Quality Assurance and now Total Quality Management”. The approach encourages including all suppliers and customers into the design and development activities of the business to produce goods and

services that satisfy the requirements of all sides.

“Total quality management can be summarized as a management

system for a customer-focused organization that involves all

employees in continual improvement. It uses strategy, data, and effective

communications to integrate the quality discipline into the culture and activities of the organization”2

Since TQM organization suppliers and customers is involved in decisions of designing and developing production; education institutions extremely need to apply the approach. Teachers, students and other education actors are teamwork who operating together to give quality product (knowledge).TQM includes setting goals and objectives, preparing rules![]()

2 http://asq.org/learn-about-quality/total-quality- management/overview/overview.html

and regulations for solving problems and building teamwork, all of which promotes long-term improvement. These standards and principles can be used in education system in order to attain an incessant enhancement. “A total quality approach to running our schools is necessary for the following reasons: 1) We live in an extremely dynamic world with depleting resources. Since schools have to equip learners to function to their fullest potential in such an environment, then the schools themselves must be dynamic and flexible. 2) The expectations of students, industry, parents, and the public in general vis à vis educational priorities, costs, accessibility, programs, and relevancy, make it imperative for schools to undergo continual assessment and improvement. 3) Economic conditions have created greater concern about economic well-being and career flexibility. Schools have to respond to this real fear of career obsolescence and career inadequacy. 4) Funding resources for education are diminishing at a rapid rate. Schools have to find innovative ways of

cutting costs without cutting quality. There is a false notion that quality is expensive. Quite the contrary, quality programs are very cost-efficient”3.

(Virtually every teacher-student interaction within a classroom may be considering a customer-supplier interaction. This relationship is very important for effective teamwork.

Each classroom may be considered![]()

3 http://husky1.stmarys.ca/~hmillar/tqmedu.htm

IJSER © 2013

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 11, November-2013 127

ISSN 2229-5518

as a user of processes and systems to supply service to students,

parents, and society. Another point of

view is that in the classroom the students along with the teacher may be considered as the "suppliers" who produce a "product" (knowledge) that future "customers" (high-grade levels, employers, graduate schools, or the society at large) will evaluate.

Outside of the classroom, students may be considered customers in the

traditional sense. Since teachers and

students must work together to satisfy their customer needs, it follows that students ought to be encouraged to be involved in instructional design and evaluation

and also empowered to assume more control over their own education)4.

From 1950 to date, Somali education faced both improvement to compete other countries and challenges that lagged behind. These reports and presentations provide highlights and facts about the different stages and history of education in Somalia. “Somalia’s educational system reflects both the vagaries of its colonial history and the political instability and uncertainty of the post- independence period. The fact that colonial Somalia was divided

between Britain and Italy meant that, at independence, the country had two

different, and largely incompatible,

educational systems. Moreover, a![]()

4 Ben A. Maguad, Caribbean Union College Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, 1999

mere 5% of the population was literate and there were only three secondary schools in the entire country. The military regime (1969-

1990) made some efforts at making

education more widely available. It overhauled the entire education system, introduced Somali as the only teaching language in primary and secondary schools (replacing English, Italian and Arabic) and engaged in strong literacy and secondary education campaigns. In the end, it succeeded in raising the literacy rate to 50%.However, the

country’s political decay since the late

1980s meant that much of this progress has been lost in recent

years. The civil war devastated the

Somali education system by destroying existing networks, facilities and teaching materials. Many schools and even the Somali National University (SNU) were requisitioned as shelters for displaced persons. Higher education in Somalia began in

1950 with the creation of the School of Politics and Administration (later

renamed School of Public Finance

and Commerce), which offered a three-year programme. In 1958, a teacher-training institute opened, followed in 1959 by a High Institute of Law and Economics. These schools became the basis for the creation of SNU in 1970. Moreover, Italy agreed to recognize these programmes as partial credit in Italian universities. Before the collapse of the Somali government and the ensuing civil strife, 15% of secondary school graduates attend SNU with full scholarships. The University had 9

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 11, November-2013 128

ISSN 2229-5518

faculties, 490 staff and 3700 students. Performance, however, varied widely across faculties: while Science and Economics had very low graduation rates (20-30%), the social sciences achieved a rate of 70-80%. In recent years, some efforts have been made to rehabilitate the Somali education system. Many private schools have appeared; however, they cater exclusively to the wealthier sectors of the population. In some peaceful areas (i.e. Somaliland), new community colleges and universities have been established, offering degrees in business, finance and education. However, the system

faces severe quality problems and a persistent lack of staff and of a uniform accreditation system. Important work is being done towards achieving these goals and it is expected that the current system will serve as a base for future developments. Disarming the private militias, however, is a prerequisite in achieving quality education in

Somalia”5.

“In the colonial period, Italian

Somaliland and British Somaliland pursued different educational policies. The Italians sought to train

pupils to become farmers or unskilled workers so as to minimize the

number of Italians needed for these

purposes. The British established an elementary education system during![]()

5 Abdulla Hussein, International Consultant: Rehabilitation of Somali Higher Education, http://dspace.cigilibrary.org/jspui/bitstream/12345

6789/15517/1/The%20Challenge%20of%20Natio n%20Building%20and%20the%20Rule%20of%2

0Law%20in%20Somalia%202005.pdf?1

the military administration to train Somali males for administrative posts and for positions not previously open to them. They set up a training school for the police and one for medical orderlies.

During the trusteeship period,

education was supposedly governed by the Trusteeship Agreement, which declared that independence could only be based on "education in the broadest sense." Despite Italian opposition, the UN had passed the Trusteeship Agreement calling for a system of public education: elementary, secondary, and vocational, in which at least elementary education was free. The authorities were also to establish teacher training institutions and to facilitate higher and professional education by sending an adequate number of students for university study abroad.

The result of these provisions was that to obtain an education, a Somali

had the choice of attending a

traditional Quranic school or the Roman Catholic mission-run government schools. The language of instruction in all these schools was Arabic, not Somali. The fifteen pre- World War I schools (ten government schools and five orphanage schools) in Italian Somaliland had an enrollment of less than one-tenth of 1 percent of the population. Education for Somalis ended with the

elementary level; only Italians attended intermediate schools. Of all

Italian colonies, Somalia received the

least financial aid for education. In

British Somaliland, the military

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 11, November-2013 129

ISSN 2229-5518

administration appointed a British officer as superintendent of education in 1944. Britain later seconded six Zanzibari instructors from the East Africa Army Education Corps for duty with the Somali Education Department. In 1947 there were seventeen government elementary schools for the Somali and Arab population, two private schools, and a teachers' training school with fifty Somali and Arab students. Until well after World War II, there was little demand for Western-style education. Moreover, the existence of two official languages (English and Italian) and a third (Arabic, widely revered as the language of the Quran if not widely used and understood) posed

problems for a uniform educational system and for literacy training at the elementary school level.

The relative lack of direction in education policy in the

prerevolutionary period under the

SRC gave way to the enunciation in the early 1970s of several goals reflecting the philosophy of the revolutionary regime. Among these goals were expansion of the school system to accommodate the largest possible student population; introduction of courses geared to the country's social and economic requirements; expansion of technical education; and provision of higher education within Somalia so that most students who pursued

advanced studies would acquire their knowledge in a Somali context. The

government also announced its

intention to eliminate illiteracy. Considerable progress toward these

goals had been achieved by the early

1980s.

In the societal chaos following the fall of Siad Barre in early 1991, schools

ceased to exist for all practical

purposes. In 1990, however, the system had four basic levels-- preprimary, primary, secondary, and higher. The government controlled all schools, private schools having been nationalized in 1972 and Quranic education having been made an integral part of schooling in the late

1970s.

The preprimary training given by

Quranic schools lasted until the late

1970s. Quranic teachers traveled with nomadic groups, and many

children received only the education

offered by such teachers. There were a number of stationary religious schools in urban areas as well. The decision in the late 1970s to bring Islamic education into the national system reflected a concern that most Quranic learning was rudimentary at best, as well as a desire for tighter government control over an autonomous area.

Until the mid-1970s, primary education consisted of four years of elementary schooling followed by four grades designated as intermediate. In

1972 promotion to the intermediate grades was made automatic (a competitive examination had been required until that year). The two cycles subsequently were treated as a single continuous program. In 1975

the government established universal primary education, and primary education was reduced to six years. By the end of the 1978-79 school

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 11, November-2013 130

ISSN 2229-5518

years, however, the government reintroduced the eight-year primary school system because the six-year program had proved unsatisfactory. The number of students enrolled in the primary level increased each year, beginning in 1969-70, but particularly after 1975-76. Primary schooling theoretically began at age six, but many children started later. Many, especially girls, did not attend school, and some dropped out,

usually after completing four years. In

1981 Somalia informed the UN Conference on the Least Developed Countries that the nomadic population was "omitted from the formal education program for the purposes of forecasting primary education enrollment." In the late

1970s and early 1980s, the government provided a three-year

education program for nomadic

children. For six months of each year, when the seasons permitted numbers of nomads to aggregate, the children attended school; the rest of the year the children accompanied their families. Nomadic families who wanted their children to attend school throughout the year had to board

them in a permanent settlement. In addition to training in reading, writing, and arithmetic, the primary curriculum provided social studies courses using new textbooks that focused on Somali issues. Arabic was to be taught as a second language beginning in primary school, but it was doubtful that there were enough qualified Somalis able to teach it beyond the rudimentary

level. Another goal, announced in the

mid-1970s, was to give students some modern knowledge of agriculture and animal husbandry. Primary school graduates, however, lacked sufficient knowledge to earn a living at a skilled trade. In the late

1980s, the number of students

enrolled in secondary school was less than 10 percent of the total in primary schools, a result of the dearth of teachers, schools, and materials. Most secondary schools were still in urban areas; given the rural and largely nomadic nature of the population, these were necessarily boarding schools. Further, the use of Somali at the secondary level

required Somali teachers, which entailed a training period. Beginning in the 1980-81 school year, the government created a formula for allocating post primary students. It assumed that 80 percent of primary school graduates would go on to further education. Of these, 30 percent would attend four-year general secondary education, 17.5 percent either three- or four-year courses in technical education, and

52.5 percent vocational courses of one to two years' duration. The principal institution of higher education was Somali National University in Mogadishu, founded in

1970. The nine early faculties were agriculture, economics, education,

engineering, geology, law, medicine,

sciences, and veterinary science. Added in the late 1970s were the faculty of languages and a combination of journalism and Islamic studies. The College of Education, which prepared secondary-school

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 11, November-2013 131

ISSN 2229-5518

teachers in a two-year program, was part of the university. About 700 students were admitted to the university each year in the late

1970s; roughly 15 percent of those

completed the general secondary course and the four-year technical course. Despite a high dropout rate, the authorities projected an eventual intake of roughly 25 percent of general and technical secondary school graduates. In 1990 several other institutes also admitted secondary school graduates. Among these were schools of nursing, telecommunications, and veterinary science, and a polytechnic institute. The numbers enrolled and the duration of the courses were not known. In addition, several programs were directed at adults. The government had claimed 60 percent literacy after the mass literacy campaign of the mid-1970s, but by early 1977 there were signs of relapse, particularly among nomads. The government then established the National Adult Education Center to coordinate the work of several ministries and many voluntary and part-time paid workers in an

extensive literacy program, largely in rural areas for persons sixteen to forty-five years of age. Despite these efforts, the UN estimate of Somali literacy in 1990 was only 24

percent”6.

“Private schools were closed or nationalized in 1972, and all education was put under the

jurisdiction of the central government.![]()

6 http://countrystudies.us/somalia/52.htm

In 1975 primary education was made compulsory. A minimum of eight years of schooling at the primary

level is mandatory; however, many prospective students, particularly among the nomadic population, cannot be accommodated. Secondary education lasts for four years but is not compulsory. A mass literacy campaign was conducted in the mid-1970s, but there is some

question as to how lasting the effects were, particularly among the nomadic population. In the mid-1980s, literacy remained low, perhaps 18% among adult men and 6% among adult women. In 1990 UNESCO estimated the adult literacy rate to be 24.1% (males, 36.1%; females, 14.0%). An estimated 2% of government expenditure was allocated to education in the period between 1986 and 1993.

In 1985, there were 196,496 pupils and 10,338 teachers in 1,224 primary schools, and 45,686 students and

2,786 teachers in secondary schools. The same year, 5,933 secondary

school children were in vocational

courses. The Somali National University, located at Mogadishu, also had a technical college, a veterinary college, and schools of public health, industry, seamanship and fishing, and Islamic disciplines. All institutions at the higher level had

817 teachers and 15, 672 students in

1986.

During 1992, Somalia was in a state of anarchy and not only did the

country's economy collapse, but its

educational system as well. Few schools were operating and even the

IJSER © 2013

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 11, November-2013 132

ISSN 2229-5518

Somali National University was closed in 1991. As of 1996, some schools were beginning to reopen”7. “Education services in Somalia are

provided by a variety of stakeholders, including Community Education

Committees, regional administrations,

community-based organizations, educational umbrella groups and networks, NGOs and religious groups. The role and reach of governments in overseeing the delivery of education has increased, albeit slowly. Despite major improvements in overall school enrolment over the last eight years, only 710,860 children out of an estimated 1.7 million (UNDP projection) of primary school age children – 42 per cent of children - are in school. Of those at school, 36

per cent are girls. Only 15 per cent of the teaching force are women with

the majority being unqualified. The average primary student teacher ratio

is 1:33. These national figures hide significant regional level variations.

Poor learning outcomes are reflected in the high repetition and drop-out

rates and low examination pass rates. Less than 38 per cent of those

enrolled in 2001/2002 in grade one successfully progressed to grade five

in 2006/2007. Only 37 per cent of girls who transitioned from primary

school took the Form Four exam in

2011/2012. The demand for secondary school education

continues to grow steadily, yet girls

make up only 28 per cent of students at that level”8.

(Abdurrahman Oct 26, 2010)

“currently I can say the education system in Somalia is recovering and even some part of Somalia such as punt land and Somaliland have been established a situation that the educational institutions can operate. Therefore worth noting is that the universities in Somalia they offer postgraduate studies although the quality of education in Somalia is not possible to compare to some developing countries in Africa any

elsewhere”9. Reports of education assessments conducted in Somalia

indicate that the school enrollment is very low in Somalia especially girls’

enrollment is lower. Factors that hindered school enrollment in

Somalia include poor quality of provision education services,

insufficiency access to education and insecurity exist in the country.

“Enrolment rates in Somalia are among the lowest in the world. Only

four out of every ten children are in school. Many children start primary

school much later than the recommended school-entry age of six

and many more dropout early. Secondary school education

enrolments are even weaker. Girls are particularly badly affected with

only a third of girls enrolled in school in South Central Somalia and many

dropping out before completing their primary education. The drive to get![]()

![]()

7

http://www.nationsencyclopedia.com/Africa/Som alia-EDUCATION.html

8 http://www.unicef.org/somalia/education.html

9

http://www.nationsencyclopedia.com/Africa/Som alia-EDUCATION.html

IJSER © 2013

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 11, November-2013 133

ISSN 2229-5518

parents to bring their children to free Government schools will be boosted by plans to build and renovate schools, train and support teachers, increase the capacity of Ministries and provide youth training facilities. The Initiative includes basic education for 6–13 year olds as well as alternative basic education for out of school children including pastoralists and the internally displaced. There are also plans for basic skills training for half a million

14–18 year olds who are often seen as the age group most at risk of being recruited into armed groups or

criminal gangs. However no funding has so far been pledged for this part

of the initiative. “Go 2 School is very

ambitious, but it is an essential and achievable initiative,” said UNICEF Somalia Representative, Sikander Khan. “Education is the key to the future of Somalia – we have already lost at least two generations. An educated youth is one of the best contributions to maintaining peace and security in Somalia. I know the Somali parents recognize this – and I believe that the international community does as well. ”Sunday marks the start of the school year in South Central Somalia – where enrolment figures due to continuing insecurity, conflict and displacement are lowest. “Giving children and young people an education is crucial for their own future and that of their family and community.” said the Somali Federal Government’s

Minister for Human Development and

Public Services, Dr. Maryan

Qasim. “But education is also crucial

for maintaining peace and stability. Education can be Somalia’s true peace dividend.” In June this year, during the first Education Conference to take place in Mogadishu for two decades, Prime Minister Abdi Farah Shirdon, pledged that the Government would give education

the same priority as defense and

security. The State Minister for Education in Somaliland, Ahmed Nur Fahuye expressed his full support for the Initiative saying: "We are all now required to teach or to learn." The Minister of Education for Puntland, Abdi Farah Said Juxa, said, “Our children must come first. We all need to come together and help educate our children. Everyone must play

their part, government, parents, teachers and the community at large. Education is our future. The efforts

we put in today will be rewarded tomorrow.” Local businesses,

politicians, religious leaders and

elders have all pledged support for the campaign. The Somali Diaspora is also engaged with award winning novelist Nuruddin Farah and supermodel Iman, with both urging support for the Initiative. The Go 2

School Initiative, which will cost US$117 million over three years, is being supported by UNICEF, WFP and UNESCO along with a number of International NGOs. Funds from the European Union, USAID and the

UK’s Department for International Development, DFID have been granted to a consortium of NGOs. Japan, the Global Partnership for Education and the Danish International Development Agency,

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 11, November-2013 134

ISSN 2229-5518

DANIDA, have made commitments whilst others have expressed interest. So far there have been pledges or promises that would cover 50% of the required funding for the 2013/14-

2015/2016 school years”10.

1990s, community-based groups known as Community Education Committees and development agencies have been largely responsible for the delivery of education services in Somalia. The Ministries of Education are gradually taking over with improved systems and capacities particularly at central levels. 2. Quality of Education- Overall, the quality of teaching across all three zones remains poor due to limited opportunities for teacher training and the lack of a salary system managed by a central Education Ministry. Most teachers are trained by UNICEF and NGOs and incentives are paid by local communities with top-ups from UNICEF and partners. 3. Conflict

affected by armed conflict, there have also been reports of recruitment of children from schools. Because of continued insecurity, UNICEF relies on local partners, Community Education Committees and umbrella organizations with operational access![]()

10

http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/media_7032

4.html

in Central South Somalia. Limited partner capacity for reporting, monitoring and effective financial management continues to be a constraint. 4. Absence of Planning Data- Effective planning has been hampered by the lack of accurate and reliable data, including Educational Management Information System (EMIS) and enrolment data, while regular monitoring in insecure areas

is difficult and often impossible. However, in 2011 the Education Ministries in Puntland and Somaliland with financial and technical support from UNICEF conducted a Primary School Census. In Central South Somalia, UNICEF, the Education Ministry and education stakeholders are currently conducting a pilot

school survey in some districts of

Mogadishu”11.

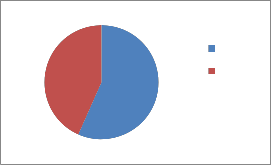

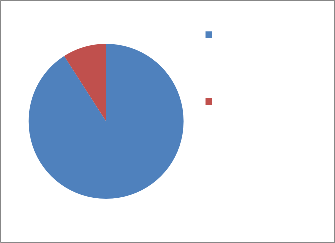

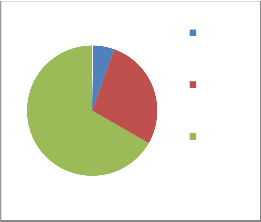

My research focused on higher education and I looked at contexts that support quality and health management of institutions. The special points that my questionnaire considered first were access to materials and resources, school management, decision making approaches, distance and cost, enrollment and dropout, teaching environment, qualification of teachers and teacher-student ratios. I made observations and face to face interviews. I distributed 100 questionnaires but I received the response of 60 persons. The![]()

11

http://www.unicef.org/somalia/education_111.ht ml

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 11, November-2013 135

ISSN 2229-5518

respondents of my questionnaire were male and female (34 male and

26 female) who comprised of

teachers, students, university chairs and parents (18 teachers, 33 students, 3 university chairs and 6 parents.

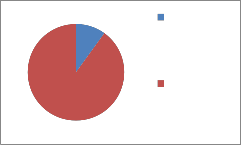

90%

10%

Univesities that have their own Compus

Univesities that reside rent houses

Male

26 Female

34

Teachers

3

6

18 Students

University

33 Chairs

Parents

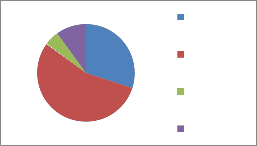

I made observations on 20 universities in Mogadishu and notice that only 2 universities in Mogadishu have their own campuses and the rest universities reside small rent houses with poor hygiene.

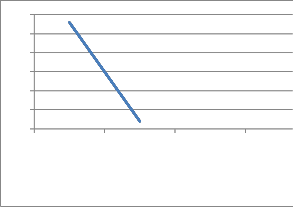

According to the respondents and reports from other sources there is both and increase and decrease of universities in Somalia. Before the collapse of the state in 1991 there was only one university in Somalia (Somali National University). This university became the most quality one in Horn Africa and accepted

many different students from different countries. The university was destructed by the wars happened in the country and its compound is a dwellings for internally displaced people. The universities in the

country now are privately owned institutions which their quality of teaching and learning is very poor. The figure 3.1 below shows the increase and decline of universities in Somalia.

100

80

60

40

20 # of

0 Universities

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 11, November-2013 136

ISSN 2229-5518

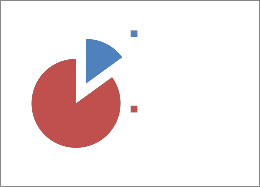

Fifty six respondents of my questionnaire confirmed that the quality of higher education in Somalia decreased and quantity increased but four answered that both quality and quantity of universities in Somalia improved. The figure 3.2 below

shows the opinion of the respondents about the quality of the universities in Somalia

60

50

40

aware nor consulted what is learned in different semesters and teachers prepare for them and teach in classes. 3 of the respondent students said that they receive outline of the

syllabus that will be taught in different semesters but they do not have

ability to change/increase what is in

or to select some and remove others.

0 # of students unaware their school syllabus

30

20

10

0

Quantity increased and qualty decreased

Both quality and quantity improved

3

# of students participated in school syllabus setting

30

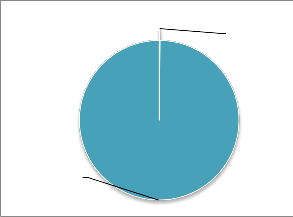

Only 3 out of the 20 universities I visited in Somalia have library and reading resources for students.

85%

15%

%of universities

have library and reading resources for students

% of universities have not library and reading resources for students

52 out of the respondents agreed that

85% of teachers at universities in

Somalia are undergraduate teachers. This mean Bachelors teach

Bachelors and there is small number of master and PHD teachers at the

30 out of 33 respondent students highlighted that they are neither

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 11, November-2013 137

ISSN 2229-5518

universities.

% of undergrad uate teachers/u nqualified

% of graduate teachers/ Qualified teachers

66.70%

5.50%

27.80%

PHD

teachers

Master degree teachers

Bachelor degree teachers

teachers

12 of the interviewed teachers were Bachelor degree, 5 were master degree and 1 was PHD.

Four chairs of four different universities interviewed said that they do not consult either students or parents when designing the curriculum of their universities. They said that teachers and university administrators select books and courses of different faculties for the students. Then students select the faculty they need but cannot select the course or books they need.

Five parents responded my questionnaire answered that they are unaware what is going in the universities and what is taught their children.

My study of the case was very important and I noticed that the teaching learning quality of some universities in Somalia is poor. I also noticed that TQM approach is not applied by all institutions in Somalia. I encourage institutions and

universities in Somalia to implement national and international principles

and standards of education to

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 11, November-2013 138

ISSN 2229-5518

improve the quality of education and enhance the skills and professional careers of the raising generations. The quality management gives originations which apply it credibility and reputation to compete their counterpart.

New government has opportunity to set policy and minimum standards to follow for the practitioners of education. These minimum standards will support institutions of education

to have guidelines to follow and will prevent to open institutions that

increase nothing to the society.

[1] Abdulraheem M. A. Zabadi (2013) University of Business & Technology (UBT), College of Engineering& Information Technology (CEIT), P.O.Box 110200, Jeddah21361, SaudiArabia. E-

Mail: abdulraheem@ubt.edu.sa

[2] American International Journal of Contemporary Research Vol. 2 No. 1; January 2012

[3] Angeline M. Barrett1 Rita Chawla- Duggan2 John Lowe2 Jutta

Nikel2 Eugenia Ukpo1 (2006) THE

CONCEPT OF QUALITY IN EDUCATION: A REVIEW OF THE

‘INTERNATIONAL’ LITERATURE ON THE CONCEPT OF QUALITY IN

EDUCATION, EdQual Working Paper

No. 3, 1University of Bristol, UK 2University of Bath, UK

[4] Benjamin Powella, Ryan Fordb, Alex

Nowrastehc (2008) Somalia after state collapse: Chaos or

improvement? aBeacon Hill Institute, Suffolk University, United

States, bSan Jose State University, United States, cGeorge Mason University, United States

[5] Centre for Developing-Area Studies – McGill University 11 November 2005: The Challenge of Nation Building and the Rule of Law in Somalia: Roundtable Discussion

[6] Charity Tinofirei (2011) UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA

[7] Dave Nave (2002) How To Compare

Six Sigma,Lean and the Theory of Constraints: A framework for choosing what’s best for your organization

[8] Dirgo, Robert (2006) Look Forward Beyond Lean and Six Sigma : A Self- perpetuating Enterprise Improvement Method

[9] Don F. Westerheijden (2007) The changing concepts of quality in the assessment of study programmes, teaching and learning, University of Twente, Center for Higher Education Policy Studies, CHEPS, P.O. Box

217, 7500 AE Enschede,The

Netherlands

[10] Federiga Bindi Director of Jean Monnet Centre of Excellence, University of Rome Tor

Vergata federiga.bindi@uniroma2.it, Marco Amici Research Grant Holder,

University of Rome Tor Vergata -

Jean Monnet Centre of Excellence and Consultant for the Italian School of Public

Administration marco.amici@uniroma

2.it , Andrea Amici Research Grant Holder, University of Rome Tor Vergata - Jean Monnet Centre of Excellence an.amici@gmail.com , Learning from Afghanistan and

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 11, November-2013 139

ISSN 2229-5518

Somalia: How to improve capacity building in fragile situations

[11] Hannah Elwyn, Catherine

Gladwell and Sarah Lyall of Refugee

Support Network (2012).“I just want

to study”:Access to Higher Education for Young Refugees and Asylum Seekers, http://refugeesupportnetwor k.org/sites/all/sites/default/files/files/I

%20just%20want%20to%20study.pdf

[12] Harry Hare June 2007, SURVEY OF ICT AND EDUCATION

IN AFRICA: Somalia Country Report

1, http://www.mbali.info/doc382.htm

[13] Heli Mattisen (Vice Rector Of

Academic Affairs, Tallinn University), Birgit Kuldvee (Curricula Accreditation and Quality Management Assistant, Tallinn

University) QUALITY MANAGEMENT VS QUALITY CONTROL: LATEST DEVELOPMENTS IN ESTONIAN HIGHER EDUCATION

[14] Helmut Fennes and Hendrik Otten (2008) Quality in non-formal education and training in the field of European youth work

[15] Hugh Willmott Judge (1997) Making Learning Critical: Identity, Emotion, and Power in Process of Management Development Institute of Management University of Cambridge, UK

[16] Ina NIKOLOVA-JAHN (2008) ASPECTS OF TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT IMPLEMENTATION Technical University, Sofia, Bulgaria

[17] International Journal of Current Research Vol. 33, Issue, 3, pp.149-153, March, 2011, REVIEW ARTICLE TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT IN EDUCATION

[18] Jean Claude Ah-Teck (2012) Mauritian Principals’ Responses to Total Quality Management Concepts in Education, DEAKIN UNIVERSITY

[19] Marie Lall, Carol Campbell

and David Gillborn (2004) Parental

Involvement in

Education, http://extra.shu.ac.uk/ndc/

downloads/reports/RR31.pdf

[20] Markus Virgil Hoehne (2010) Diasporic engagement in the educational sector in post-conflict Somaliland: A contribution to peace building?, www.diaspeace.org

[21] Ministry of Education, Culture

& Higher Education, National

Education Plan, 2011

[22] Mohammad A. Ashraf and Yusnidah Ibrahim College of Business, Universiti Utara Malaysia,

06010, UUM Sintok, Kedah E-mail:

mashraf@monisys.ca, yibrahim@uu m.edu.my and Mohd. H. R. Joarder School of Business, United International University, 80-8A Dhanmandi R/A, Dhaka 1209, Bangladesh E-

mail: joarder@uiu.ac.bd (2009) QUALITY EDUCATION MANAGEMENT AT PRIVATE UNIVERSITIES IN BANGLADESH: AN EXPLORATORY STUDY

[23] Peter T. Leeson (2007) Better off stateless: Somalia before and

after government collapse, George

Mason University, MSN 3G4, Fairfax, VA 22030, USA

[24] Phu Van Ho (2011) TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT

APPROACH TO THE INFORMATION SYSTEMS

DEVELOPMENT PROCESSES: AN EMPIRICAL STUDY, Virginia

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 11, November-2013 140

ISSN 2229-5518

Polytechnic Institute and State

University

[25] R.O. Oduwaiye, A. O.

Sofoluwe, D.J. Kayode (2012) TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT AND STUDENTS’ ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE IN ILORIN METROPOLIS SECONDARY SCHOOLS, NIGERIA, Department of Educational Management, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, NIGERIA

[26] REBECCA WINTHROP AND MARSHALL S. SMITH (2012) A NEW FACE OF EDUCATION BRINGING TECHNOLOGY INTO THE CLASSROOM IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD, BROOKE SHEARER WORKING PAP E R S E R I E S

[27] Salami CGE and Ufoma

Akpobire O (2013) Application of total quality management to the Nigerian education system, Delta State University, Department of Management and Marketing, PMB

95074 Asaba, Nigeria Delta State

Polytechnic, School of Business Studies, Department of Business Administration and Management

[28] Shafie Sharif Mohamed and

Mahallah Uthman Ibn Affan (2012) Evaluating Quality Performance of Somali Universities, International Islamic University

Malaysia http://www.arabianjbmr.com

/pdfs/KD_VOL_1_12/5.pdf

[29] Somalia Federal Republic

G2S Initiative: Educating for

Resilience (2013‐2016) Strategy

Document, http://www.unicef.org/som

alia/SOM_resources_gotoschool.pdf

[30] Tara Bahadur Thapa, TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT IN

EDUCATION, Academic Voices A

Multidisciplinary Journal Volume 1, N0. 1, 2011

[31] UNICEF, Press release

Massive campaign to get one million Somali children into school to be launched,http://www.unicef.org/infoby country/media_70324.html

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 11, November-2013

ISSN 2229-5518

141

IJSER IS) 2013