International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 2, Issue 11, November-2011 1

ISSN 2229-5518

Pilot study of the Osseous Morphological Changes in the Temporomandibular Joint in Subjects with Bilateral Missing Lower Posterior Teeth

Nasser Aly, Hasnah Hashim, Harlina Saleh, Dzuraida Abdullah

Abstract - We evaluated osseous morphological changes in the temporomandibular joints (TMJ) in subjects with bilateral missing lower posterior teeth. We selected 13 men with class І dental occlusion who fulfilled the study criteria. They were assigned to control group compri sing 8 subjects with complete set of teeth, and test group comprising 5 subjects with bilateral missing lower posterior teeth. Two cephalometric radiographs were taken for each subject, one as base line and the other after 7 months for linear measurements of the mandibular condyle. The test group showed an increase in glenoid fossa depth (base line and after 7 months, and a slight decrease in the anterior-posterior dimension of the. The control group showed an increase in glenoid fossa depth and an increase in the anterior-posterior dimension of the condyle Our findings do not support the hypothesis that loss of occlusal support causes osseous changes in the TMJ in men. However, this could be due to the small sample size and shorter st udy duration. We suggest that these changes be studied using a larger sample size to achieve stronger conclusions.

—————————— ——————————

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is composed of two compartments: the lower compartment contains the head of the mandibular condyle and the upper compartment The TMJ is a highly specialized articulation. It differs from the other synovial joints in that its articular surfaces are composed of dense fibrous tissue that functions as cartilage

1.It is also an arthrodial joint permitting gliding motion 2-3. Temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) are the most common chronic orofacial pain condition 4. A constellation of signs and symptoms including joint tenderness and pain on function and headache may also be features 5, 6. Three main groups of etiological factors are involved in the development of TMDs: anatomical factors including occlusion, neuromuscular factors and psychogenic factors

7. Functional natural dentition with more than 20 teeth is

required for acceptable oral health and may important for maintaining a healthy body mass index into old age 8. Adequate occlusal support enables efficient chewing and may indirectly prevent TMDs 9. Reportedly, osseous

The duration of this study was 12 months. In the first three months, 13 subjects were selected from the out-patient list of a dental clinic for enrolment. They included 8 subjects with a complete dentition and 5 subjects with bilateral missing lower posterior teeth. This study was approved by the University Sains Malaysia Research and Ethics

contains the glenoid fossa and the articular eminence. The articular disc separates the compartments each of which has a synovial sac for nutrition and lubrication. changes in the articular components of the TMJ and variations in the osseous components of the TMJ correlate with occlusal disharmony 10. For example, unilateral or bilateral absence of all posterior teeth increases the risk of pain and joint sounds 11. Further, condylar positioning during clenching is related to the posterior occlusal support

12, and loss of such support leads to noticeable condylar

movements 13.

Therefore, the osseous morphology of the TMJ in subjects with bilateral missing lower posterior teeth should be significantly different from that in subjects with a complete dentition. To validate this hypothesis, changes in the osseous morphology of the TMJ with bilateral missing lower posterior teeth and those with a complete dentition were evaluated by linear cephalometric measurements.

Committee (Approval no [218.4. (2.1)]). All subjects gave written informed consent for participation.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: male gender 14, 15, class I occlusion, age between 35 and 70 years, absence of systemic diseases causing bone resorption. Subjects were excluded if they had abnormal occlusion (class II or class

III), oro-facial muscular problems, and symptoms of TMDs,

IJSER © 2011

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 2, Issue 11, November-2011 2

ISSN 2229-5518

history of an accident involving the TMJ or medication affecting bone resorption. Further, staff members, subjects with any other conditions considered unsuitable for the study by the investigators and those withdrew from the study were excluded.

For each subject cephalograms were obtained at the

baseline and 7 months of follow up. The following linear measurements were carried out 16:

Glenoid depth, the distance from the deepest point of the glenoid fossa to the plane joins the vertex of the postglenoid process to the top of the convexity of the articular tubercle. Anteroposterior condyle dimension, the distance between the most prominent points on the anterior and posterior surfaces of the condoyle perpendicular to the mediolateral axis.

Morphometric findings, including the changes over the study period, are summarized in Table 1. Subjects with a complete dentition showed increased glenoid depth. However, these subjects had an increase in anterior- posterior condylar dimension and slight decrease in anterior facial height at 7 months compared with the

baseline (Figures 1A, 1B).

Anterior facial height, the distance from the sub-nasal septum to the menton.

An Orthoralix 9200 panoramic system (Gendex Dental Systems, Des Plaines, IL, USA)was used for cephalograms with the following specifications 17:

magnification 1.1, default kV factor 70 kV for 0.8 s in small

–size subjects, 74 kV for 0.8 s in medium –size subjects and

78 kV for 0.8 s in large-size subjects, peak voltage 60-84 kV, tube current 3-15 mA, exposure time 0.16-2.50 s.

Data were collected and entered into SPSS version 18. Due to the small sample size, we could not use P values; therefore, median and interquartile range (IQR) was used to describe the numerical variables.

The subjects with bilateral missing lower posterior teeth had increased glenoid depth, a slightly decreased anterior posterior condylar dimension and slightly increased anterior facial height at 7 months compared with the baseline (Figure 2A).

IJSER © 2011

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 2, Issue 11, November-2011 3

ISSN 2229-5518

Table 1: Show Median and Interquartile Range base line and after 7 months

Variable Median (IQR) Difference | |

Ant. Posterior Condyle-1 1.1500 (0.305) Base | Increase by 0.020 Decrease by 0.008 Increase by 0.085 Increase by 0.002 Decrease by 0.135 Increase by 0.168 |

Ant. Posterior Condyle-1 1.1700 (0.180) After | Increase by 0.020 Decrease by 0.008 Increase by 0.085 Increase by 0.002 Decrease by 0.135 Increase by 0.168 |

Ant. Posterior Condyle-2 1.1300 (0.575) Base | Increase by 0.020 Decrease by 0.008 Increase by 0.085 Increase by 0.002 Decrease by 0.135 Increase by 0.168 |

Ant. Posterior Condyle-2 1.1100 (0.505) After | Increase by 0.020 Decrease by 0.008 Increase by 0.085 Increase by 0.002 Decrease by 0.135 Increase by 0.168 |

Glenoid depth-1 Base .8650 (0.353) | Increase by 0.020 Decrease by 0.008 Increase by 0.085 Increase by 0.002 Decrease by 0.135 Increase by 0.168 |

Glenoid depth-1 After 1.0550 (0.215) | Increase by 0.020 Decrease by 0.008 Increase by 0.085 Increase by 0.002 Decrease by 0.135 Increase by 0.168 |

Glenoid depth-2 Base .8600 (0.210) | Increase by 0.020 Decrease by 0.008 Increase by 0.085 Increase by 0.002 Decrease by 0.135 Increase by 0.168 |

Glenoid depth-2 After .7500 (0.310) | Increase by 0.020 Decrease by 0.008 Increase by 0.085 Increase by 0.002 Decrease by 0.135 Increase by 0.168 |

Ant. Face-1 Base 7.2850 (0.478) | Increase by 0.020 Decrease by 0.008 Increase by 0.085 Increase by 0.002 Decrease by 0.135 Increase by 0.168 |

Ant. Face-1 After 7.1200 (0.713) | Increase by 0.020 Decrease by 0.008 Increase by 0.085 Increase by 0.002 Decrease by 0.135 Increase by 0.168 |

Ant. Face-2 Base 7.1700 (0.735) | Increase by 0.020 Decrease by 0.008 Increase by 0.085 Increase by 0.002 Decrease by 0.135 Increase by 0.168 |

Ant. Face-2 After 7.2100 (0.545) | Increase by 0.020 Decrease by 0.008 Increase by 0.085 Increase by 0.002 Decrease by 0.135 Increase by 0.168 |

IJSER © 2011

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 2, Issue 11, November-2011 4

ISSN 2229-5518

Table 2: above shows the mean for the base line measurement and after 7 months of measurement.

N | Mean Rank | Sum of Ranks | |

Ant. Posterior Condyle-1 Negative Ranks After - Ant. Posterior Positive Ranks Condyle-1 Base Ties Total | 1a | 8.00 | 8.00 |

Ant. Posterior Condyle-1 Negative Ranks After - Ant. Posterior Positive Ranks Condyle-1 Base Ties Total | 7b | 4.00 | 28.00 |

Ant. Posterior Condyle-1 Negative Ranks After - Ant. Posterior Positive Ranks Condyle-1 Base Ties Total | 0c | ||

Ant. Posterior Condyle-1 Negative Ranks After - Ant. Posterior Positive Ranks Condyle-1 Base Ties Total | 8 |

a. Ant. Posterior Condyle-1 < Ant. Posterior Condyle-1

b. Ant. Posterior Condyle-1 > Ant. Posterior Condyle-1

IJSER © 2011

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 2, Issue 11, November-2011 5

ISSN 2229-5518

N | Mean Rank | Sum of Ranks | |

Ant. Posterior Condyle-1 Negative Ranks After - Ant. Posterior Positive Ranks Condyle-1 Base Ties Total | 1a | 8.00 | 8.00 |

Ant. Posterior Condyle-1 Negative Ranks After - Ant. Posterior Positive Ranks Condyle-1 Base Ties Total | 7b | 4.00 | 28.00 |

Ant. Posterior Condyle-1 Negative Ranks After - Ant. Posterior Positive Ranks Condyle-1 Base Ties Total | 0c | ||

Ant. Posterior Condyle-1 Negative Ranks After - Ant. Posterior Positive Ranks Condyle-1 Base Ties Total | 8 |

a. Ant. Posterior Condyle-1 < Ant. Posterior Condyle-1

b. Ant. Posterior Condyle-1 > Ant. Posterior Condyle-1 c. Ant. Posterior Condyle-1 = Ant. Posterior Condyle-1

From the table's legend that 1 subject had a higher Ant. Posterior condyle before treatment than after their treatment. However,

7 subjects had a higher Ant. Posterior condyle after treatment and 0 subject saw no change in their Ant. Posterior condyle.

Ant. Posterior Condyle-1 After - Ant. Posterior Condyle-1 Base | |

Z Asymp. Sig. (2-tailed) | -1.404a .160 |

a. Based on negative ranks.

b. Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test

A Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test showed that a Ant. Posterior condyle before and after treatment did not elicit a statistically significant change. (Z = -1.404, P = 0.160).

IJSER © 2011

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 2, Issue 11, November-2011 6

ISSN 2229-5518

N | Mean Rank | Sum of Ranks | |

Ant. Posterior Condyle-2 Negative Ranks After - Ant. Posterior Positive Ranks Condyle-2 Base Ties Total | 2a | 2.50 | 5.00 |

Ant. Posterior Condyle-2 Negative Ranks After - Ant. Posterior Positive Ranks Condyle-2 Base Ties Total | 2b | 2.50 | 5.00 |

Ant. Posterior Condyle-2 Negative Ranks After - Ant. Posterior Positive Ranks Condyle-2 Base Ties Total | 1c | ||

Ant. Posterior Condyle-2 Negative Ranks After - Ant. Posterior Positive Ranks Condyle-2 Base Ties Total | 5 |

a. Ant. Posterior Condyle-2 After < Ant. Posterior Condyle-2 Base b. Ant. Posterior Condyle-2 After > Ant. Posterior Condyle-2 Base c. Ant. Posterior Condyle-2 After = Ant. Posterior Condyle-2 Base

From the table's legend that 2 subject had a higher Ant. Posterior condyle before treatment than after their treatment. There were also 2 subjects had a higher Ant. Posterior condyle after treatment and only 1 subject saw no change in their Ant. Posterior condyle.

Ant. Posterior Condyle-2 After - Ant. Posterior Condyle-2 Base | |

Z Asymp. Sig. (2-tailed) | .000a 1.000 |

a. The sum of negative ranks equals the sum of positive ranks.

b. Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test

A Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test cannot be done since the sum of negative ranks equals to the sum of positive ranks.

≈ Comparing between Group 1 (p-value = 0.160) and Group 2, maybe we can say that Group 1 more significant.

IJSER © 2011

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 2, Issue 11, November-2011 7

ISSN 2229-5518

N | Mean Rank | Sum of Ranks | |

Glenoid depth-1 After - Negative Ranks Glenoid depth-1 Base Positive Ranks Ties Total | 2a | 4.25 | 8.50 |

Glenoid depth-1 After - Negative Ranks Glenoid depth-1 Base Positive Ranks Ties Total | 6b | 4.58 | 27.50 |

Glenoid depth-1 After - Negative Ranks Glenoid depth-1 Base Positive Ranks Ties Total | 0c | ||

Glenoid depth-1 After - Negative Ranks Glenoid depth-1 Base Positive Ranks Ties Total | 8 |

a. Glenoid depth-1 After < Glenoid depth-1 Base b. Glenoid depth-1 After > Glenoid depth-1 Base c. Glenoid depth-1 After = Glenoid depth-1 Base

From the table's legend that 2 subject had a higher Ant. Posterior condyle before treatment than after their treatment. However,

6 subjects had a higher Ant. Posterior condyle after treatment and again 0 subject saw no change in their Ant. Posterior cond yle.

Glenoid depth-1 After - Glenoid depth-1 Base | |

Z Asymp. Sig. (2-tailed) | -1.334a .182 |

a. Based on negative ranks.

b. Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test

A Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test showed that a Ant. Posterior condyle before and after treatment did not elicit a statistically significant change. (Z = -1.334, P = 0.182).

N | Mean Rank | Sum of Ranks | ||

Glenoid depth-2 After - Glenoid depth-2 Base | Negative Ranks Positive Ranks Ties | 3a | 2.33 | 7.00 |

Glenoid depth-2 After - Glenoid depth-2 Base | Negative Ranks Positive Ranks Ties | 2b | 4.00 | 8.00 |

Glenoid depth-2 After - Glenoid depth-2 Base | Negative Ranks Positive Ranks Ties | 0c |

IJSER © 2011

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 2, Issue 11, November-2011 8

ISSN 2229-5518

![]()

Total 5 a. Glenoid depth-2 After < Glenoid depth-2 Base

b. Glenoid depth-2 After > Glenoid depth-2 Base

c. Glenoid depth-2 After = Glenoid depth-2 Base

However, from the table's legend above shows that 3 subject had a higher Ant. Posterior condyle before treatment than after their treatment. In contradiction, 2 subjects had a higher Ant. Posterior condyle after treatment and 0 subjects saw no change in their Ant. Posterior condyle.

Glenoid depth-2 After - Glenoid depth-2 Base | |

Z Asymp. Sig. (2-tailed) | -.135a .893 |

a. Based on negative ranks.

b. Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test

A Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test showed that a Ant. Posterior condyle before and after treatment did not elicit a statistically significant change. (Z = -0.135, P = 0.893).

≈ Comparing between Group 1 (p-value = 0.182) and Group 2 (p-value = 0.893), maybe we can say that Group 1 is more significant since the p-value for Group 1 is lower than Group 2.

N | Mean Rank | Sum of Ranks | ||

Ant. Face-1 After - Ant. Face-1 Base | Negative Ranks Positive Ranks Ties | 6a | 4.83 | 29.00 |

Ant. Face-1 After - Ant. Face-1 Base | Negative Ranks Positive Ranks Ties | 2b | 3.50 | 7.00 |

Ant. Face-1 After - Ant. Face-1 Base | Negative Ranks Positive Ranks Ties | 0c |

IJSER © 2011

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 2, Issue 11, November-2011 9

ISSN 2229-5518

![]()

Total 8 a. Ant. Face-1 After < Ant. Face-1 Base

b. Ant. Face-1 After > Ant. Face-1 Base

c. Ant. Face-1 After = Ant. Face-1 Base

Same from table before, table above also a higher by 6 subject had a higher Ant. Posterior condyle before treatment than after their treatment. Only subjects had a higher Ant. Posterior condyle after treatment and 0 subject saw no change in their Ant. Posterior condyle.

Ant. Face-1 After - Ant. Face-1 Base | |

Z Asymp. Sig. (2-tailed) | -1.540a .123 |

a. Based on positive ranks.

b. Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test

A Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test showed that a Ant. Posterior condyle before and after treatment did not elicit a statistically significant change. (Z = -1.540, P = 0.123).

N | Mean Rank | Sum of Ranks | |

Ant. Face-2 After - Ant. Negative Ranks Face-2 Base Positive Ranks Ties Total | 1a | 1.50 | 1.50 |

Ant. Face-2 After - Ant. Negative Ranks Face-2 Base Positive Ranks Ties Total | 4b | 3.38 | 13.50 |

Ant. Face-2 After - Ant. Negative Ranks Face-2 Base Positive Ranks Ties Total | 0c | ||

Ant. Face-2 After - Ant. Negative Ranks Face-2 Base Positive Ranks Ties Total | 5 |

a. Ant. Face-2 After < Ant. Face-2 Base b. Ant. Face-2 After > Ant. Face-2 Base

IJSER © 2011

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 2, Issue 11, November-2011 10

ISSN 2229-5518

N | Mean Rank | Sum of Ranks | |

Ant. Face-2 After - Ant. Negative Ranks Face-2 Base Positive Ranks Ties Total | 1a | 1.50 | 1.50 |

Ant. Face-2 After - Ant. Negative Ranks Face-2 Base Positive Ranks Ties Total | 4b | 3.38 | 13.50 |

Ant. Face-2 After - Ant. Negative Ranks Face-2 Base Positive Ranks Ties Total | 0c | ||

Ant. Face-2 After - Ant. Negative Ranks Face-2 Base Positive Ranks Ties Total | 5 |

a. Ant. Face-2 After < Ant. Face-2 Base b. Ant. Face-2 After > Ant. Face-2 Base

c. Ant. Face-2 After = Ant. Face-2 Base

From the table's legend that 1 subject had a higher Ant. Posterior condyle before treatment than after their treatment. However, 4 subjects had a higher Ant. Posterior

condyle after treatment and 0 subject saw no change in their Ant. Posterior condyle.

Ant. Face-2 After - Ant. Face-2 Base | |

Z Asymp. Sig. (2-tailed) | -1.625a .104 |

a. Based on negative ranks.

b. Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test

A Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test showed that a Ant. Posterior condyle before and after treatment did not elicit a statistically significant change. (Z = -1.625, P = 0.104).

≈ Comparing between Group 1 (p-value = 0.123) and Group 2 (p-value = 0.104), maybe we can say that Group 2 is more significant since the p-value for Group 2 is lower than Group 1.

IJSER © 2011

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 2, Issue 11, November-2011 11

ISSN 2229-5518

4 Discussions

An increase in the load per unit of bite force within the temporomandibular joints (TMJ) with greater use of anterior teeth has been reported 18. Several epidemiological investigations and animal studies have shown that manipulation of teeth (extraction, extirpation, and high occlusal contacts) can induce changes in the TMJ 19-22. An increase in degenerative changes in the TMJ was observed in patients with missing molars 23. Previous studies 24-26 have concluded that missing mandibular posterior teeth represents a cumulative risk factor in the presence of internal derangement of the TMJ. A previous study indicated that there was a small but significant increase in the prevalence of missing mandibular posterior teeth found in subjects with disk displacement and that the absence of these teeth may accelerate the development of degenerative joint diseases; however, no evidence that shortened dental arches causes overloading of the joints and teeth was provided, which indicates that neuromuscular regulatory systems are controlling maximum clenching strength under various occlusal conditions 27. Further, the studies performed by Kayseri/Nijmegen et al. have shown that shortened dental arches comprising anterior and premolar teeth in general fulfill the requirements of a functional dentition 28. In this study, only male subjects were enrolled to avoid female subjects with post-menopausal osteoporosis that might increase the rate of bone resorption and affect the results. The limited sample size is attributable to the Ethical Committee guideline that the number of subjects must not exceed 16. All equipments were calibrated and safe for use. Further, the radiographic parameters were standard because the supplier of the panoramic system adjusts and calibrates the equipment to the accepted standards. Wedel et al16 reported the use of linear measurements of the condyle to asses TMJ morphology. An increase in glenoid depth observed in all subjects, indicates increase rate of bone resorption of the glenoid fossa. The slight increase in anterior facial height noted in subjects with bilateral missing lower posterior teeth may be a result of occlusal disturbance due to missing teeth and the slight decrease in this parameter in the subjects with a complete dentition may be attributable to functional attrition.

The results of this study indicate different changes of the osseous morphology of the TMJ between the subjects. Within the study limitations, our findings do not support the view that loss of occlusal support is a causative factor for osseous changes in the TMJ. Future studies should investigate these changes in a larger sample size to drive a stronger conclusion.

.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

IJSER © 2011

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 2, Issue 11, November-2011 12

ISSN 2229-5518

[1] Dubrul E L, Sicher H. Oral Anatomy.7th ed, St. Louis: CV Mosby Co., 1980.

[2] Bell W E. Temporomandibular Disorders: Classification, Diagnosis. Management. 3rd ed, Chicago: YearBook Medical. 1990. [3] Okeson J P. Management of Temporomandibular Disorders and Occlusion. 2nd ed, St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1989.

[4] Cellic R, Jerolimov V, Ziatric D K. Relation of slightly limited mandibular movement to temporomandibular disorders. Braz Dent J 2004 8:

15-20.

[5] Pullingen G A, Seligmen A D. Quantification and validation of predictive values of occlusal variable in temporomandibular disorders using a multifactorial analysis. J Prosthet Dent 2000 83: 66-75.

[6] Gary R J, Quayle A, Hall C A. Physiotherapy in the treatment of temporomandibular joint disorders: a comparative study of four treatments methods. Br Dent J 1994 7: 68-75.

[7] Thor Hendrickson D. Damned if we do and damned if we do not? Br Dent J 2007 202: 38-39.

[8] Sheiham A, Steele J G, Marcenes W, et al. The relationship between oral health status and body mass index among older people: a national survey of older people in Great Britain. Br Dent J 2002 192: 703-706.

[9] Ciancaglini R, Gherlone E F, Radaelli G. Association between losses of occlusal support and symptoms of functional disturbances of the

masticatory system. J Oral Rehabil 1999 26: 248-253.

[10] Ciancaglini R, Gherlone E, Radaelli G. Unilateral temporomandibular disorder and a symmetry of occlusal contacts. J Prosthet Dent 2003 9:

180-185.

[11] Sarita P T, Kreulen C M, Witter D, Creugers N H. Signs and symptoms associated with TMD in adults with shortened dental arches. Int J Prosthodont 2003 16: 265-270.

[12] Yamashita S, Maruyama Y, Kirihara T, et al. Condylar positioning during clenching related to loss of posterior occlusal support. Nihon

Hotetsu Shika Gakkai Zasshi 2007 51: 699-709.

[13] Seedorf H, Seetzen F, Scholz A, et al. Impact of posterior occlusal support on the condylar position. J Oral Rehabil 2004 31: 759-763.

[14] Glowacki J, Kelly M. Osteoporosis and vitamin D deficiency among postmenopausal women with osteoarthritis undergoing total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg 2003 12: 2371-2377.

[15] Garnero P, Sornay-Rendu E, Deimas P D. Biochemical markers of bone turnover, endogenous hormones and the risk of fractures in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res 2000 15: 1526-1536.

[16] Wedel A, Carlsson G E, Sagne S. Temporomandibular joint morphology in a medieval skull material. Swed Dent J 1978 12: 177-182. [17] White S C, Pharoah M J. Oral Radiology: Principles and Interpretation. St. Louis: Mosby, 2000.

[18] Rues S, Lenz J, Turp C, et al. Muscles and joints forces under variable equilibrium states of the mandible. Clinical Oral Investing 2010 [Epub ahead of print].

[19] Oberg T, Carlsson G E, Fajers C M. The temporomandibular joint. a morphologic study on a human autopsy material. Acta Odontol Scand

1971 29: 349-384.

[20] De Boever J A, Adriaens P A. Occlusal relationship in patients with pain dysfunction symptoms in the temporomandibular joints. J Oral

Rehabil 1983 10: 1-7.

[21] Kubo Y. The uptake of horseradish peroxidase in monkey temporomandibular joint synovial after occlusal alteration. J Dent Res 1987 66:

1049-1054.

[22] Glueck C J, McMahon R E, Bouquot J E, et al. Thrombophilia, hypofibrinolysis, and alveolar osteonecrosis of the jaws. Oral Surg Oral Med

Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1996 81: 557-566.

[23] Kuwahara T, Maruyama T. Relationship between condylar atrophy and tooth loss in craniomandibular disorders. J Osaka Univ Dent Sch.

1992 32: 91-96.

[24] Ishimaru J, Handa Y, Kurita K, Goss A N. The effect of occlusal loss on normal and pathological temporomandibular joints: an animal study.

J Craniomaxillofac Surg 1994 22: 95-102.

[25] Ishimaru J, Goss A N. A model for osteoarthritis of the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofacial Surg 1992 50: 1191-1195.

[26] Ishimaru J I, Kurita K, Handa Y, et al. Effect of marrow perforation on the sheep temporomandibular joint. Int J Oral Maxillofacial Surg 1992

21: 239-242.

[27] Hattori Y, Satoh C, Seki S, et al. Occlusal and TMJ loads in subjects with experimentally shortened dental arches. J Dent Res 2003 82: 532-536. [28] Kanno T, Carlsson E. A review of the shortened dental arch concept focusing on the work by the Kayser/Nijmegen group. J Oral Rehab

2006 33: 850-856.

IJSER © 2011

Interna tional Journal of Scientifi c & Engineering Research, Volume 2, Issue 11, November-2011 13

ISSN 2229-5518

![]()

Figure lB

IJSER 2011

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 2, Issue 11, November-2011 14

ISSN 2229-5518

IJSER ©2011

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 2, Issue 11, November-2011 15

ISSN 2229-5518

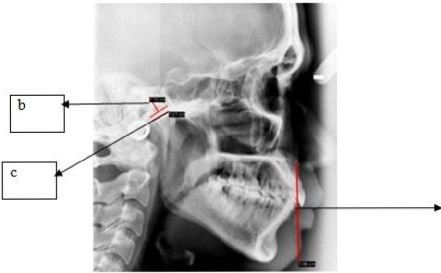

Figure 1. Lateral cephalograms of a subject with a complete dentition obtained at the base line (B) and 7 months of follow-up (A).

1B: Baseline lateral cephalometric radiograph for a subject with a complete set of teeth

a - anterior face height, b - depth of glenoid, c - anterior-posterior dimension of the condyle

1A: Lateral cephalometric radiograph for a subject with a complete set of teeth after 7 months

Figure 2. Lateral cephalometric radiograph of a subject with missing lower posterior teeth after 7 months.

IJSER © 2011