International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 1, January-2013

ISSN 2229-5518

1

Organizational Citizenship Behaviour of Distributed Teams: A Study on the Mediating Effects of Organizational Justice in Software Organizations

Harry Charles Devasagayam

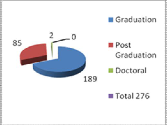

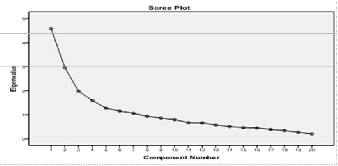

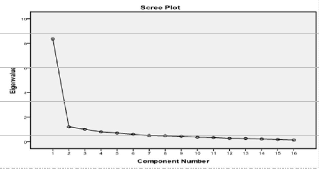

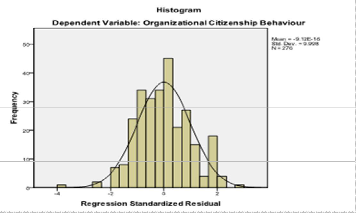

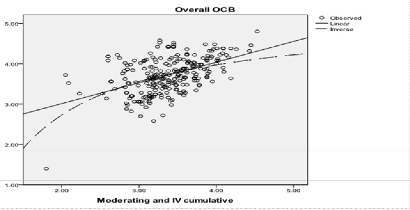

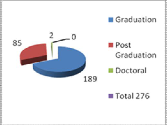

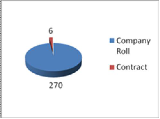

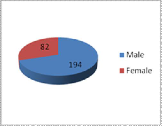

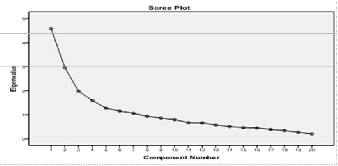

Abstract— Globalization has changed the dynamics of team working in software development. Part of adapting and accepting globalization is to work with a heterogeneous group of people located in different parts of the world with different perceptions, different attitudes and varied characteristics. The challenge for software development organizations in this scenario is to source, coordinate and manage an adept pool of professionals and help them work for complementing tasks of distributed teams, keep them motivated so as to practice extra role behaviors which will in turn help the organization grow its business. However, in order that distributed employees feel motivated, valued and respected; the organizations through their employee friendly policies create an environment for people to perceive organizational support and role efficacy. A fairly supportive system and effective utilization of competencies is likely to create a sense of organization being fair to employees. This research examined the relationships between perceptions of organizational support, role efficacy and organizational citizenship behavior by examining the mediating effects of organizational justice. A questionnaire was given to 970 software professionals. The responses of 276 people selected through a convenience sample across globally located software organizations was used for the study. The data collected from the responses was analyzed using factor analysis to rule out factors not contributing to the study. Further the data was analyzed using correlation coefficient and hierarchical regression tests to find out the relationship and mediating effects between variables. There are seven hypotheses in this study. All of which has been accepted. As predicted a significant relationship was found between perceived organizational support and organizational citizenship behavior mediated by organizational justice and role efficacy and organizational citizenship behavior mediated by organizational justice. Among the justice dimensions procedural justice was significantly related to OCB. Distributive justice has been found to predict sportsmanship, Altruism and, Conscientiousness and is negatively related to general compliance and civic virtue. Interpersonal justice was found to predict Altruism, General compliance and Civic Virtue, and negatively related to Sportsmanship and informational justice has been found to predict all the dimensions of OCB. The results show that certain behaviors are driven by the sense of being valued and trusted while other behaviors are common and individual specific. This study suggests that when software organizations seek to provide distributed members with a sense of comfort in distributed locations and employees are allowed some control over processes that determine the organizational outcome, they are more likely to perceive that their organization is supportive, feel affectively committed and are more willing to engage in citizenship behaviors. Thus software organizations desiring to create an organizational climate among distributed team that fosters organizational support, role efficacy and citizenship behavior must make every effort to improve perceptions of organizational fairness in their organizations.

Index Terms— CP-Contextual Performance, DDC-Dedicated Design Center, GDT-Globally Distributed Team, GSD-Global Software Development, OCB-Organizational Citizenship Behaviour, ODC-Offshore Development Center, OJ-Organizational Justice, POB-Pro-social Organizational Behavior, POS-Perceived Organizational Support, RBSE-Role Breadth Self Efficacy, RE-Role Efficacy, STPI-Software Technology Parks of India, SW O-Satisfaction W ith Outcomes

—————————— • ——————————

1 INTRODUCTION

he exponential growth of the Information Technology (IT) industry through the 80’s and 90’s reengineered the way traditional industry has been working. Since individual based work structure could no longer meet the demands for smarter, faster and innovative solutions, the IT industry found a remedy in using teams distributed across the world to max- imize benefits. Software organizations were divided from large organizational structures into small teams. In the last few decades, Indian software organizations adapted to distributed teams and morphed from being a domestic industry to a transnational industry. Carmel et al., 2007 further developed on this and said that distributed teams were becoming increa-

————————————————

• Harry Charles Devasagayam is a Fellow of AHRD (IIMA) and a Senior

HR professional with varied experience in different sectors. E-mail: harrycd2011@gmail.com

singly a common strategic response. A large percentage of almost 80 % of software projects are global. This has been fur- ther substantiated by researchers.

A distributed team brings together knowledge and ideas from individuals with diverse functional backgrounds and expertise to build a common solution (Sundstrom, DeMeuse & Futrell,

1990). The interaction between distributed team members adds new dimensions to the work in progress and increases a team’s problem-solving abilities which in turn lead to better performance. The “Follow the Sun” system of development enables distributed teams to work nonstop for faster delivery and time to market. With work teams located in different parts of the globe, organizations are able to establish their presence with customers worldwide. Distributed teams allow compa- nies to procure the best talent without geographical restric-

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 1, January-2013

ISSN 2229-5518

2

tions. The use of distributed teams may increase commitment, motivation and efficiency to facilitate the implementation of decisions (Gladstein, 1984). Diversity in culture, knowledge, processes, technology and skills work as combined strength of the distributed team.

However, the use of distributed teams is not without its con- cerns and problems. Since distribution of teams has become an essential part of survival for organizations, companies have moved to expand the concept of teams in-spite of the internal and external factors that might cause concerns. External fac- tors such as cross culture, language, organizational ethics and work values, political environment, systems and processes, interdependence, information sharing, power distance, indi- vidual and family issues etc., have a significant impact on the performance of distributed team members. Internal factors such as selection and deputation to onsite assignment, organi- zational support, onsite rotation policy, role, learning and de- velopment opportunities, onsite career opportunities and sup- port to family etc., creates concerns for the distributed team members. The job positioning (location, role, type of work, and rewards) comes with explicit and implicit constraints and concerns especially between onsite and offshore team mem- bers. This has given rise to favoritisms being perceived across the organization. Besides individuals interacting with their team create perceptions regarding their role and the support the organization provides to perform. If there are shared expe- riences of workplace fairness the employee’s attitude towards the organization improves and consequently improves workplace cooperation.

Performance and justice perception has received considerable research attention. Greenberg (1987) defined Organizational justice as an individual’s perception of fairness in an organiza- tion. Since this study attempts to understand the effects of jus- tice perceptions of distributed teams, an understanding of jus- tice climate is important. Justice climate is defined as “a dis- tinct team level cognition regarding how fairly the team as a whole is treated [procedurally]” (Colquitt, Noe & Jackson,

2002). Team’s cognition of fair treatment as defined by Kis- soon (2007) (Figure 1) states that individual workplace con- cerns lead to interaction between team members creating a shared meaning. Shared meaning among team members creates a perception of organizational fairness (Endres, 2007) Colquitt & Greenberg (2005) have thus created a working model of how justice perceptions relate to OCB.

Figure 1: Fairness cognition

Three analytical levels of the software orga- nizational context providing the basis

for shared meaning in distributed teams.

This theory is further supported by creating processes leading to the similarity of

justice perceptions among distributed team members. Recent research on distributed team’s justice perception has shown that team members converge on their justice perceptions but differ on citizenship behavior (Ganesh, 2008). Organizational justice has been found to be a predictor of work attitudes (Colquitt et al., 2002; Liao & Rupp, 2005), performance (Si- mons & Roberson, 2003), and citizenship behavior (Ehrhart,

2004). Shared justice perceptions among distributed teams enjoy autonomy in managing daily activities, including setting goals for the team, benchmarking their own performance, and managing decision-making processes (Manz & Sims, 1987). Being part of a distributed team member typically involves a great deal of interactions between members. This means that it can be expected that the behavior of one’s teammates may influence one’s justice perceptions and may have a large im- pact on team outcomes (Alper, Tjosvold, & Law, 2000). Re- search has found that procedural justice predicts organiza- tional trust (Hubbell & Chory-Assad, 2005; Cohen-Charash & Spector, 2001) where as distributive justice impacts perfor- mance (Cohen-Charash & Spector, 2001) and job satisfaction positively associates with overall perceptions of organizational justice (Al-Zu’bi, 2010). Additionally, organizational commit- ment is related to perceptions of procedural justice such that greater the perceived injustice, the commitment diminishes and vice versa.

There has been a growing interest in the study of organiza- tional citizenship behavior (OCB) as a workplace construct. (Moorman,1991; Organ, 1988a; Organ & Konovsky, 1989; Pod- sakoff et al., 1990; Dalal, 2005; Ganesh, 2008; and Ali et at.,

2011). Researchers have devoted attention to identifying the antecedents of organizational citizenship behavior. OCB has been connected with antecedents such as, organizational jus- tice (Aquino, 1995, Colquitt et al., 2001, Moorman, 1991, Nie- hoff & Moorman, 1993) perceived organizational support (Ei- senberger et al., 1990, Moorman et al., 1998) and role efficacy (Daniel et al., 2007).

Previous research has shown that procedural and distributive justice affects OCB (Farh et al., 1990; Moorman, 1991; Niehoff

& Moorman, 1993). A meta-analysis of OCB (Dalal, 2005) has shown that OCB is better predicted by procedural justice ra- ther than distributive justice (Konovsky & Folger, 1991; Moorman, 1991; Poddsakoff et al., 1990). Since researchers have attributed the findings to various specific outcomes such as organizational systems and authorities (Floger & Konovsky,

1989; Lind & Tyler, 1988), this study focuses on organizational justice as a whole and its relationship with OCB.

A distributed work environment is one in which at least two specific experiences of organizational justice come to the fore- front. The first experience is that of distributed employees who work in a complex environment and hence need organi- zational support. The second experience is that the employees’ need to feel that their role adds value to their project and their organization. Considering the importance of these two va- riables to distributed software development, a further under- standing of the relationship of these variables to organization- al justice and OCB was explored.

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 1, January-2013

ISSN 2229-5518

3

Further to the existing research, Eisenberger et al., (1990) in- vestigated the relationship between POS and OCB and found a significant positive relationship between the variables. In addition recent research indicates a relationship between POS, procedural justice and OCB (Lina Kogan 2004). Ganesh (2008) studied extra role performance in the light of organizational justice in software development teams and found a negative impact of overall virtualness on OCB. He further established a moderating effect of procedural justice perception on virtual- ness and OCB. Mehrdad (2009) studied the relationship be- tween organizational justice and OCB and found that organi- zational dimensions qualified by correlation coefficient tests were positively related to OCB. Ali Nirozy (2011) investigated the relationship between organizational justice and OCB me- diated by POS and found organizational justice significantly influences organizational support and OCB.

Daniel et al., (2007); Bandura, (1986); Gist & Mitchell, (1992) investigated role perceptions and OCB and established that 3 of the 4 facets of OCB relate to role perception. They have also shown that higher the role efficacy, workplace justice increases and in turn their engagement in OCB also increases.

This study is based on the above research. In addition, the study examines the mediating effect of organizational justice on the relationship between POS and OCB and RE and OCB as well.

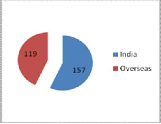

In addition to the above, the pilot study of this research re- vealed that distributed members were not treated equally. (Table 1)

Table 1: Problems of distributed teams

The above challenges could play disruptive roles in members experiencing organizational support and role perception which leads to forming their justice perception. Hence distri- buted team members have a greater potential for experiencing the lack of organizational justice in all dimensions (procedural, distributive, interpersonal and information). In the light of rapidly changing work environments in globally distributed software organizations, organizational justice and citizenship behavior remains a topic worth studying.

Thus, this dissertation attempts to get a deeper understanding of the factors that help enhance organizational justice percep- tions of organizations that motivate members to practice OCB. The primary objective of the study is to investigate how POS and role efficacy influence organizational justice which in-turn motivates distributed members practice OCB. The study also seeks to find the possibility of significant differences in the way that members of distributed organizations perceive jus- tice and practice OCB.

1.2 SIGNIFICANCE AND ASSUMPTIONS OF THE STUDY

The research covers global software development (GSD) com- panies including consulting and services, engineering and

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 1, January-2013

ISSN 2229-5518

4

products, semiconductor, telecom development, audio and video codec’s and globally shared services. The companies are headquartered in India, with each carrying out substantial software development activities in their India sites, apart from other GSD teams in the US, Ireland, Malaysia, Japan, Singa- pore, Germany, China, India, and Poland etc.

THE RESEARCH IS BASED ON THE FOLLOWING SET OF ASSUMPTIONS.

A software project team consists of people with different skill sets and talent. It consists of a manager, architect, coordinator, technical and project leaders, designers and coders, testers and QA specialists. A project team member may be assigned to a single project or more than one project. Utilization of a team member can be 100 % in one project or could be partly contri- buting to one or more than one project. Project team members may report to more than one person at a time as the person is working in a client location, but her/his work is monitored from the company’s offshore center. Distributed teams work in complex scenarios with changing project requirements and costs with external and internal hurdles. Different projects need different skills, depending on the requirement of the project. In addition project team members stay on in a project only until their skills are needed. Onsite returned employees do not get equal growth opportunities like their peers.

There are several established systems and processes of manag- ing global practices for distributed teams through the HR de- partment of organizations but implemented and managed by the project team, which at most times reveals gaps. Managers are at the receiving end as they are neither a part of creating the policies nor owners of it.

Distributed members will only be part of the team as long as their specialist skills are required. Team members come from same or different organisational backgrounds and cultures. Team members can be down the hall from each other, across the street, across the country or across the world. They can be part of the project team and geographically dispersed (charac- terised by cross culture, time-zone, work-life balance, and power distance, information exchange, mutually complement- ing tasks, collaboration and coordination)

It is also found that software industry determines value for the individuals based on competency, capability and availability together with long term business vision of the organization, business compulsions and competitive environment. Em- ployee policies and processes are influenced by business, rev- enue and profits of software organizations. Allocation of re- sources depends on roles and location of the employee. Con- tributions, consistency and longevity create respect and digni- ty for a software engineer.

In the above scenario inconsistency is likely to be perceived in the process of selection and deployment, allocation of rewards and benefits, opportunity provided for higher learning and development, assign a role, provide support to members and their family apart from members experience of being differen- tiated from their peers professionally, organizationally and

socially in the way they are valued and respected. Hence, it was assumed that employees are differentiated; and the dif- ference is visible to employees working at offshore and onsite, in India and outside India and in the product and services organizations and provides sufficient reason for perception of organizational justice.

1.3 STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

In the past two decades, the growing need for global software development, and the evolution and improvisation of the glo- bally distributed work teams have been key enablers to the stellar growth of the Indian IT industry. However, software organizations face many challenges in global delivery with pressures like cost control, round the clock development, cus- tomer proximity, faster time to market and the ability to main- tain world class quality. Software organizations have been exploring new geographies for expanding business and in- creasingly engaging in distributed models.

Revenue driven HR policies has been the reason for creating a difference among distributed members in the way they are treated in organizations. Lack of transparency, lack of global management system and insufficient resource management system are some of the reason why employees experience dif- ference. The yet another “resource” approach of people in or- ganizations restricts organizations mentality to see people as living organisms of a living entity. The growing rate of em- ployee job hopping is a proof that employees do not trust the employers. Employees motivation gets stranded as they see a visible difference between peers of onsite and offshore, India and overseas, and between organizations engaged in product development and software services and consulting in salary and benefits, roles and designations, rewards and recogni- tions, processes and procedures, learning and development, information exchange and social recognition etc., Lack of global bench mark on HR practices, competitive edge in man- aging the differences between the core and non-core talents, increasing value for global exposure and US dollars support organizations maintaining the differences.

As distributed teams are becoming a reality for many software companies, this study tries to justify that organizations moti- vate distributed teams by building transparency, fairness in processes and procedures, equality in distribution of re- sources, matured and balanced interpersonal relations and appropriate information sharing to promote justice expe- riences and performance related behaviors.

There is no evidence that an attempt has been made to study the justice perceptions and citizenship behavior of distributed team members. Theoretically, this study will add to the body of knowledge on the specific subject of OCB. From a practi- tioner’s point of view, there is a link between justice percep- tion and OCB of team members on global assignments. There- fore, it is assumed that this study will be of interest to distri- buted members, distributed organizations, specifically distri- buted software organizations, human resource professionals, and organizations which outsource its activities to distributed organizations.

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 1, January-2013

ISSN 2229-5518

5

1.4 RESEARCH QUESTION

Based on the assumptions and the problems of the study, the following research questions are drawn.

• How does organizational justice relate to OCB and what mediates the relationship between POS, role efficacy and OCB?

• How does perceived organizational support and role effi- cacy relate to OCB

• How does POS and role efficacy relate to organizational justice?

1.5 OBJECTIVES

• The primary objective of the study was to investigate how POS and role efficacy influence perception of organiza- tional justice which in-turn motivates distributed mem- bers practice of OCB.

• The study also seeks to find the possibility of significant differences in the way that members of distributed organ- izations perceive justice and practice OCB.

• This study is aimed at helping researchers and practition- ers benefit out of a deeper understanding of the factors that help enhance organizational justice perceptions of distributed organizations and motivate members to prac- tice OCB.

1.6 LIKELY BENEFITS

• The benefits of this study can be two fold. Benefits to the industry can be by drawing indicators for OCB of mem- bers working in distributed teams, which would help or- ganizations build a fair and equal system of managing re- sources. This study also aids build a HR system for global management.

• The study also aims to help professionals identify pain points of distributed team members and address the same to enable better performance and enhance repeat business opportunities.

• This study also aims to help scholars further investigate and understand the fine lines of difference between OCB practiced in consulting and service organizations as against product organizations with respect to distributed teams.

1.7 RESEARCH REPORT OUTLINE

The dissertation covers 6 chapters. Chapter I details the back- ground of the research, statement of the problem, assumptions and significance, objectives and likely benefits of the study.

In Chapter II covers the Indian IT industry, its contribution to Indian economy, global delivery systems, distributed teams, characteristics of distributed teams and factors affecting justice perception

In Chapter III the literature review of the topic is covered. The Chapter covers theories on perception, attribution and self worth of software development, globally distributed and vir- tual teams. There is also a review on POS, role efficacy, orga- nizational justice and organizational citizenship behavior. This chapter brings out knowledge and information for the reader to understand the rationale for organizational citizenship be-

havior among distributed teams.

In Chapter IV the Conceptualization and hypothesis of the

study is covered.

In Chapter V Analysis and findings of the study with through

tables, descriptions, interpretations, diagrams and graphs

In Chapter VI, results of the analysis are given in detail fol-

lowed by the conclusion of the study.

CHAPTER 2

2.1 INDIAN IT INDUSTRY

The history of the software industry in India indicates that in the 1970s, local markets for the IT industry were absent and the Government’s policy towards private enterprisers was hostile (Arora et al., 2000). IT industry in India did not see much of development during mid 70’s due to restrictions on import of computer peripherals, high import tax, strict Foreign Exchange and the Regulation Act.. In 1974, for the first time in the history of the software industry in India, the Burroughs Corporation, a major American manufacturer of business equipment directed their sales agent Tata Consultancy Servic- es (TCS) in India, to depute programmers for installing soft- ware systems for an American client (Ramadurai, 2002). Soon others followed which included foreign IT firms that formed compatible joint ventures notable among them being IBM.

In the late 1980s, India faced an acute balance of payment problem due to the limited availability of foreign exchange and mounting external debt. Being cash constrained the Gov- ernment of India launched a ‘liberalization policy’ in 1984, giving privatization and globalization unprecedented momen- tum. Major policy reforms included recognition to software development as an industry to invest and make it eligible for incentives similar to domestic industries and reducing import tariffs which liberalized exposure to the latest technologies. This was done to compete globally and capture a share of global software exports. With drastic changes in higher educa- tion after 1983 liberalization made a major impact on privately funded colleges which later was the foundation for creating IT clusters. To compliment this growth Special Economic Zones (SEZ) were launched in several states.

In 1990, Department of Electronics (DoE) introduced the con- cept of Software Technology Park (STP’s) in India. STP’s were allowed establishment with basic infrastructure, dependable power supply, tax exemptions and also given 100% ownership for foreign firms. During this period India saw dramatic changes with heavy investments on higher education and booming privately funded engineering colleges to make India ready with technical manpower resources. High investments in higher education and the formation of prestigious engineer- ing colleges and policy reforms to allow foreign investments in 1991 enabled significant growth in development. From just programming and documentation work India emerged to im- plementation, R&D, out sourcing and diversified itself to be- come a global hub for software and IT enabled services. Since the 1990s multinational software corporations focused on glo- balization by exploiting the opportunities available across the

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 1, January-2013

ISSN 2229-5518

6

world. IT outsourcing was one such to bring in a globally in- tegrated economy. India for its strong value proportion be- came a target destination for multinationals for back end IT operations. Thus India witnessed an increase of off-shoring jobs offered by global outsourcers, like never before.

The advantage of the Indian software industry (Budhwar, Lu- thar, & Bhatnagar, 2006a; Budhwar, Varma, Singh, & Dhar,

2006b) was based on the availability of qualified and talented manpower at much lower costs than other developing econo- mies. American firms were able to find cost effective ways to develop software products in India due to India’s rapidly ex- panding professionally qualified people with good communi- cation and language skills. With more and more qualified pro- fessionals being sourced by the US, gradually, a new global market opportunity emerged with a regular stream of skilled engineers being sent abroad on software programming as- signments.

As the Indian IT industry advanced to the center stage Minis- try of information technology, (2003) supported the efforts by setting up a science and technology bureaucracy to coordinate government-administrated projects relating to information technology. A number of different government agencies, for- merly under the Ministry of Science and Technology con- cerned with IT, were brought together into an integrated Min- istry of Information Technology (MIT). It has since undertaken a large number of projects to make India an IT Super Power.

2.2 IMPACT OF INDIAN IT INDUSTRY ON ECONOMY

The Indian IT industry contributed 6.1% of the GDP in 2010 and the industry employees contributed about USD 4.2 billion to the exchequer. Additionally, the industry’s operating and capital expenditure was estimated at around USD 30 billion, while consumer spending from employees amounted to USD

21 billion in FY2009 (NASSCOM, 2010). The sector aggregated revenues of USD 73.1 billion in FY 2010, a growth of 5.4% over FY2009 and generated direct employment for 2.3 million people and indirect employment for an estimated 8.2 million people . 30 % of the total employee base is women and 60 %of companies offer employment to people with special needs. 58

% of the employees originate from Tier-II/III cities. The indus- try has also played a key role in regional development with IT-BPO intensive states accounting for over 14 % of the GDP with 58 %of engineering graduates. The industry has contri- buted to the development of the middle class and has im- proved their standard of living. In addition to this a strong sense of social responsibility has been imbibed with over USD

50 million spent in CSR activities in FY2009. India holds the majority share of the global market currently at 51% in tech- nology and 62% in BPO, Contribution to national GDP is 6.1% in 2010 The Indian IT industry has businesses in over 70 dif- ferent countries enabling learning and adapting to different cultures through employee movement.

2.3 INTEGRATED GROWTH ENGINEERED DISTRIBUTED MODEL

With the interdependence and integration between economies globalization of markets has grown. Part of the strategy was expanding the market by creating overseas units, outsourcing business, joint ventures and technical collaborations. NASS- COM, 2009 reported that 50% of fortune 500 companies use global software development and 60% operate remote centers. It further states that 50% of global software companies out- source some or all of their projects. Management consulting firm A. T. Kearney (2007) reported that at least 1000 global software development companies have outsourced their projects to India in the year 2009.

The growing competition, both from within the country and abroad, has provoked many Indian IT companies to look to foreign markets seriously to improve their competitive posi- tion and increase business. TCS pioneered the global delivery model for IT services with its first offshore client in 1974. This experience also helped TCS bag its first onsite project - the Institutional Group & Information Company (IGIC), a data centre for ten banks, which catered to two million customers in the US. Following the success of TCS, many other software companies started exploring overseas markets.

Between 1990 and 2010, the Indian IT sector had become the country’s premier growth engine and crossed several signifi- cant milestones in terms of revenue, growth, employment generation and value creation. The industry saw an unprece- dented growth of over 50% YOY from 1998 to 2001. Through- out the 2000s, India's outsourcing industry, both business process outsourcing and IT outsourcing grew steadily. The US accounted for 60 % of revenues from the export of products and services, and Europe accounted for about 22 %. Industry verticals such as Banking, Financial Services and the Insurance sector (BFSI) led the segment with 41% of revenues, and the balance was from other segments like hi-tech, telecom, manu- facturing and retail. As per NASSCOM reports, for the finan- cial year 2010, the IT sector aggregated revenue of USD 73.1 billion, out of which Software business accounted for USD 63.7 billion and generated direct employment for 2.3 million people. Export revenues grossed USD 50.1 billion in FY 2010 with 69% from IT-BPO revenues. In 2010 India had 51% of the total world market share of the software off-shoring market despite political and logistic constraints.

Domestic IT revenues grew at almost 8.5 % to reach INR 1,088 billion in FY2010. Domestic IT services grew by 12 % in FY2010. The industry has diversified beyond traditional IT with Indian and MNC service providers collaborating and competing to build the industry. With an aggregated total of

450 Indian software delivery centers in 60 countries globally the distributed team model became popular. A study by Goldman Sachs suggests that India is expected to be the world's third-largest economy by 2035, next only to the United States and China. A.T. Kearney (2007) quoted that India has become the third most attractive foreign investment destina- tion globally.

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 1, January-2013

ISSN 2229-5518

7

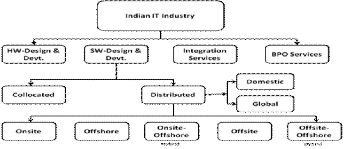

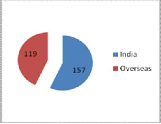

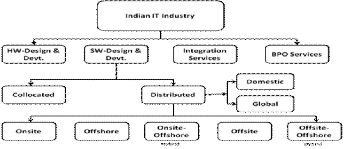

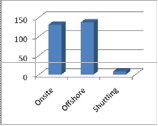

The exponential growth of the IT business has promoted the pattern of delivery to manage global IT business (Figure 2). The following pattern is drawn to indicate how the industry has evolved into distributed development.

Figure 2 : Global Software Development

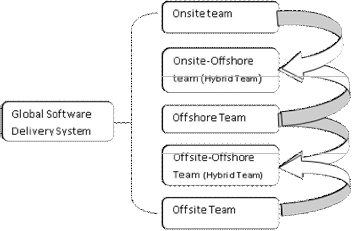

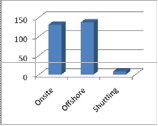

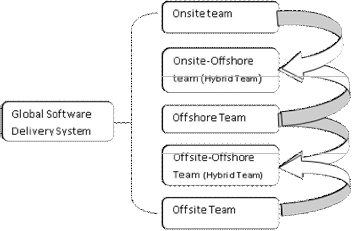

2.4 GLOBAL SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT AND DELIVERY SYSTEM

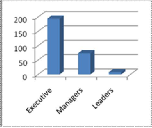

Global software development (Figure 3) is the coordination of software developmental activities across sites. It is also the management of distributed repositories of assets that contri- bute to those applications. "Distribution" is a broad term that can apply to one or more dimensions, including people, arti- facts, platforms, and ownership or decision rights. As compa- nies expand around the world, multiple sites become a "team of teams" contributing to a global delivery chain. Each team may own a module or component they deliver upstream for integration with components from other locations or compa- nies, culminating in a final application or product. Teams may belong to the same organization, division, or company, or to different ones. Each member of the team is assigned to a role or type of work and divided according to their role and loca- tion.. The following are some of the roles.

• Developmental role-Technical contributions

• Fulfillment role-Project management, coordination, rela-

tionship management

• Leadership Role-Providing leadership to the organization

• Investment role- Equity investors

• Sales and Business Development role-Technical and busi- ness sales

Distributed development and outsourcing run parallel to each other. Outsourcing work is distributed between the service provider’s onsite centre and the offshore development centre, thereby giving the client the advantage of both models. The distribution of work depends on the type of project. Usually

20-30 %of the work is done by the onsite centre and the rest is done offshore The Onsite - Offshore model is generally pre- ferred in cases where the project is complicated and is ex- pected to continue for a long period of time. Although the tasks accomplished on-site and offshore are different, they are developed in consonance with each other. Working together in this fashion leads to an exchange of information, interaction, listening, cooperation and coordination between members. Global organizational distributions, across multiple sites col- laborate on a single component to be delivered in the chain.

Sites may be very large or, as a result of workforce mobility be as small as a single individual. This research has attempted to bring out a comprehensive understanding of different distri- buted teams, from the researcher’s experiences of creating and managing distributed teams, and information obtained from the websites of different companies.

Figure 3 : Global Delivery System

2.1.3.1 On-site

The On-site team is a set of skilled professionals from across

the organization deployed at the clients’ location either for the

entire duration of the project, or a part of it. The On-site team

is used when the scope of the project is repetitive and open-

ended. Technology transfer, knowledge transfer, revenue gen-

eration, building domain specific knowledge, etc., are some of

the benefits of using an onsite team. A more accurate descrip- tion of the onsite team would be to label them as a staff aug- mentation team working for overseas clients.

2.1.3.2 Offshore

The Offshore team is beneficial when customers need to quick-

ly ramp up the team, reduce costs, engage in round-the-clock

development, and/ or reduce risks attached to new product

development. An offshore development team is used when

there is a contract with a long-term agreement on prices and

the size of the project is large. A large fraction of the project is

executed offshore with the Indian firm responsible for deli-

very schedule adherences. Many established Indian software firms have more than one development centre.. It can be a dedicated design centre, domain based business unit or a technology driven organization etc.

2.1.3.3 Onsite – Offshore

The Onsite - Offshore team, or Hybrid team, is a combination

of work executed both onsite and offshore. The Hybrid team

executes work distributed between the service provider’s on-

site centre and the offshore development centre. The on-site

technical team is placed in proximity to the client at critical

phases of the project’s life cycle to maximize efficiency and

optimize costs. In this model, the Indian company sends a few software professionals to the client’s site based on requirement for analysis or training in a particular system. These profes- sionals then bring back the specifications to India and have a

larger team develop the software offshore. If the project is

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 1, January-2013

ISSN 2229-5518

8

large, a couple of Indian professionals remain at the custom- er’s site acting as liaisons between the project leaders offshore, and the clients. Sometimes these onsite professionals are needed for emergency operations and for reassuring the clients that the project is proceeding according to schedule. To execute such projects, a firm needs not only skilled profes- sionals, but also a software development process and metho- dology and the ability to manage software development.

2.1.3.4 Offsite

In the Offsite team, the service provider works in the vicinity

of the client, i.e. the service provider will be located within the

same city/country as that of the client. The Offsite team

enables the client and the service provider to interact face-to-

face on a regular basis which is mutually advantageous. This

is especially beneficial when the client’s requirements are not

well defined and are expected to change during the course of

the project. The offsite model works well when clients are not

in a position to expand their facilities all off a sudden to ac- commodate the service provider’s team and requirements, but at the same time need to outsource.

2.1.3.5 Offsite-Offshore

The Offsite - Offshore team is one of the most successful and

popular outsourcing models employed today. In this model,

the service provider’s software development centre is located

near the client’s premises, and the job is distributed between

the offsite centre and an offshore development centre located

in a different country. The offsite centre acts as the mediator.

Usually, the off-site team handles 20-30 % of the total work

and the offshore team manages the rest.

The Offsite - Offshore team is preferred when clients out-

source to a service provider located near them, for control on

the development process. When the Offsite - Offshore team is

used, the offsite team works on requirement analysis and

hands over the specifications to the offshore development cen-

tre, where the development and testing of the software is

done. The off-site centre then implements at the software at

the client’s site. The management and administration costs

involved in maintaining both the centers inhibit many service

providers from choosing this model.. Also the cultural differ-

ences arising from the geographical differences between the

offsite centre and offshore centre at times also cause problems.

2.1.3.6 Expatriates as distributed members

Well trained workforces are pooled from across the locations

to manage complex tasks of software organizations. Multina-

tional corporations send their representatives to their subsidi-

aries primarily to transfer responsibilities to their Indian coun-

ter parts. However, as organizations keep expanding, special-

ists in different domain and areas are given relatively longer

period of assignment. In the same way when Indian software

organizations open their overseas center, accomplished Indian

professionals are deputed to shoulder build, operate and

transfer responsibility to their local counterparts. Researchers have noted that the ability of managers to work cross- culturally is a crucial success factor in competing in the global marketplace (Dadfar & Gustavsson, 1992; Granstrand, Hakan-

son, & Sjolander, 1993). Organizations suffer from a tendency

to be lenient to the expatriates when they are distributed to locations across the world. The leniency on higher pay, better treatment, higher role and extraordinary support develops a kind of a justice perception among members.

2.5 CHARACTERISTICS OF DISTRIBUTED TEAMS

Indian software organizations practice more than one system of distributing work. Projects get distributed where competen- cies are found, and people get distributed where projects are available. Developmental activities may be distributed along many dimensions and have distinct characteristics (Gumm DC, 2006). This gives rise to a few questions: Who or what is distributed and at what level? Are people or artifacts distri- buted? Are people dispersed individually or dispersed in groups?

Understanding of purpose, roles and structure-A distributed team has a clear mission and charter with long-term and short- term objectives depending on the type and size of the project. A common objective, shared vision and rewards are some of the important strategies around which a distributed team works. The team members have the expertise, and are empo- wered to create and innovate for the organization within the ambit of the distributed project goals. Teams draw strength and direction from a deep, shared understanding of a common purpose.

In an ideal situation, roles are clearly defined and work as- signments are evenly distributed, though not necessarily fixed. Team members take responsibility for tasks willingly, and assume responsibility for tasks. Team members are willing to work outside their defined roles in order to help the team. Leadership is shared, and the issue of control is resolved to the team’s satisfaction. Individual talents are utilized.

Project management and control- When distributed members are attached to the client’s onsite location the project is ma- naged by more than one person whereby the client manages the delivery while the technical quality is managed by the dis- tributed member’s parent organization. Team tracking and uniform delivery- Progress towards specified goals needs to be tracked. Each member has to compliment the role of other members.

Knowledge and information sharing- Developers need to communicate and collaborate closely or at times work inde- pendently on parts of a project. Needs of the project and dis- tributed members determines communication. Software arti- facts (code, designs, documentation, processes and step / phase wise development etc.) need to be shared and kept con- sistent. Information sharing between team members, sites / locations, client and customer, manager and team member on a regular basis helps distributed members.

Managing diverse environments- A distributed team may not have the balance in composition of gender, culture, age and experience. Organizational and cultural barriers may compli- cate globally distributed work (E. Carmel & R. Agarwal, 2001). The differences in cultural and communication behaviors and coping with the diversity of operating in different environ-

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 1, January-2013

ISSN 2229-5518

9

ments, needs to be managed (R. D. Battin, R. Crocker, J. Kreid- ler, & K. Subramanian, 2001).

Virtuality is managed by the bandwidth established between the distributed and the locations. These include email, inter- net, voice and data transfers, chats etc., Distance is managed by onsite deployment or offshore working or building a hybr- id model of working between onsite and offshore.

Asynchronous management- The essence of Asynchronous Management™ is where a global distributed team is working on its own schedules / deadlines, but presents up-to-date in- formation when called upon. This concept of Asynchronous Management started developing where managers are located in every time zone and region. Though each manager operates within the particular region’s go-to-market strategy, he con- tinues to be a part of the global team with global responsibili- ties and deliverables.

Shared Control- In a distributed work environment, it is criti- cal to establish the responsibility of the work that can be de- veloped and executed at a local level, and ones that need ap- proval from the core development centre to help plan processes that can balance the local and regional needs against the overall budget, and revenue impacting decisions handled globally. Many a time, project control may be exercised either from the core development centre or from the client’s or cus- tomer’s office. In the absence of an awareness of roles, there is a possibility of mismanaging control, and misrepresenting the contribution of members.

2.6 FACTORS AFFECTING PERCEPTIONS

While appreciating the contribution of distributed teams to the growth of the IT industry, we need to understand that growth has not come without certain explicit and implied challenges. The challenges of managing the human dimension of such teams cannot be overstated. The rapid growth of the Indian software industry has created some unique human and lea- dership challenges.

Policies and processes- Software organizations lack focus in maintaining a uniform or balanced policy between onsite and offshore in selecting potential resources, assigning roles, pro- viding transit accommodation for self and family, processing visa and social security measures, equitable compensation, regular interaction, regular update on management and re- source management plans for post deployment.

Short duration-Many a times, onsite deployment is short lived, reducing the opportunity for forward integration either with the team or with the organization. Frequently changing projects, roles and locations due to the short duration of the project reduces consistency in performance and commitment to the organization.

Changing teams and roles- Members are shuffled from project to project and location to location to enable better re- source utilization. However, such movement of resources re- duces focus on their contribution and creates a sense of not being valued by the organization. It also reduces their chances

of developing their potential for future assignments.

Tools and technology- The dependency on development kits is very high as they move from one technology to another and from one project to another. In a distributed location, there could be a delay in providing the required technical assis- tance. Due to the non availability of tools, technologies and required project related support; members depend and tap open source tools. However, this might bring about many IP related issues to the organization.

Insufficient resources- In order to reduce cost and become more competitive, organizations engage minimum manpower in distributed locations, forcing a member into handling addi- tional work. This attitude results in extended hours of work and working on holidays and weekends.

Learning and development opportunity- As members are assigned with set tasks and deadlines the time and opportuni- ty for higher learning becomes difficult. Training individuals for the next assignment also becomes very difficult as mem- bers are bound by tight schedules of delivery. Members do feel left out when they don’t get an opportunity for higher learning. A refusal of opportunity for higher learning will sub- sequently make them feel redundant. Fear of becoming re- dundant will force people to continue to look for challenging assignments and feel that their organization does not care about building their potential.

Post deployment career plan- The amount of haste and hurry shown in fulfilling the onsite requirements of the client is not shown to a member who is assigned to the onsite work. In the absence of a clear resource management plan (RMP), members are bound to feel that they will not get the kind of support needed for post assignment employment.

Opportunity for global exposure- Opportunity for global ex- posure is yet another self actualization move that members of software organizations look for as they keep climbing up the ladder. A domestic company which does not have an overseas client or a product development company which is building a product for specific requirement of a country may not have the need to give an overseas exposure or be able to afford a complete life cycle exposure. Lack of opportunity for global exposure will make people feel the need for a better assign- ment.

Life cycle exposure- Members may be assigned to routine work. Roles and responsibilities are divided between the team members to enable quicker and effective delivery. However, as members look for fast track growth, they would like to be exposed to the life cycle development (from requirement col- lection to post delivery support). Organizations must see the potential in every member and try to provide an opportunity for life cycle exposure.

Equal opportunity employer- Practically organizations may find it difficult to provide the aspired role to everyone. Often individuals’ capability and potential are not considered while

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 1, January-2013

ISSN 2229-5518

10

assigning a role. Clients’ need and time constraints to deliver determines the role of a member in organizations. Hence, role mismatch, denial or lack of opportunity to work in the desired role is some of the challenges which make members feel that their organizations are not supportive.

Accommodating personal and family needs- Distributed work comes with problems of finding a suitable accommoda- tion to the member and his family, helping the member to get a family visa, providing competitive salary, health and insur- ance support to both the member and their family. Members might feel ignored if any of this is not taken care of.

Holidays and compensatory offs- Any disturbance at work is seen as contributing to workplace stress. Members who do not get holidays at regular intervals such as weekly off, annual holidays and national & festival holidays feel that they are not getting enough relaxation. As a result of this, they are likely to feel stressed, worn-out and exhausted.

Update about the business and organization- Personal touch with members has been a motivator, especially for those who are posted onsite. Lack of personal touch and information sharing make the members feel lonely.

Participation in management building- Not sharing focus areas and growth plans leave members in the dark. The mem- bers who are not taken into confidence and made inclusive are likely to experience a sense of aloofness and feel sidelined.

Keeping excited- Members are to be kept excited about the type of work they do, to make the best use of onsite assign- ments. In the absence of continued excitement, a member might lose interest in his job and start looking for assignments that might be of interest to him. Repeat, mundane and redun- dant type of work often causes heart burn and makes the em- ployee develop an intention to quit. A sense of importance and fulfillment is important in keeping a member excited.

Rewards and appreciation- Insufficient rewards such as un- equal salary, lack of onsite promotion, increment and rotation policy de-motivate the member. Power distance: Inability and lack of face to face interaction with the leaders and team members is yet another important reason why employees feel distanced from their organization.

Dignity and respect- How members are treated within their organization, among their team members, by the client in the distributed location is a vital parameter in keeping the team going.

Distance-Distance can reduce team cohesion in groups colla- borating remotely. Distributed team members may not have the opportunity to meet face-to-face and discuss issues. Mem- bers eating together, sharing an office, or working late togeth- er to meet a deadline, all contributes to a feeling of being part of the team. These opportunities are diminished by distance.

Communication and Coordination- An important line con-

necting distributed team members is communication. Syn- chronous communication becomes less common due to time zones and language barriers. Even when communication is synchronous, the communication channels, such as conference calls or instant messaging, are less rich than face-to-face and co-located group meetings. Developers may take longer to solve problems because they lack the ability to step into a neighboring office to ask for help. When managers must man- age across large distances, it becomes more difficult to stay aware of each person’s task, and how they are interrelated. Different sites often use different tools and processes which can also make coordinating between sites difficult.

CHAPTER 3

LITERATURE REVIEW

This chapter includes major streams of literature necessary for establishing the foundation of the study. The first stream of literature relates to theories on the process of perception and social exchange resulting in satisfaction with outcome beha- viours. The second stream reviews research in the areas of global software development and distributed teams. In this section we examine how software teams are formed and normed for a unique pattern of work. We also examine other names used to denote dispersed software development which include virtual and open source system of software develop- ment. The third stream of literature examines globally distri- buted teams. In this section, we examine how perceived orga- nizational support and role efficacy experiences of distributed members help create and sustain perception across teams in software organizations and how perceptions influence discre- tionary and voluntary performance behaviours in distributed team. The fourth stream of literature examines the control fac- tors of either strengthening or weakening the relationship be- tween the criterion and the outcome variables. Upon these streams of literature the theoretical framework for the study is developed. The chapter concludes with a summary and the implications of the literature review.

The theories on perceptual process include important assump- tions, interaction and exchange behaviours of members work- ing in teams. It primarily discusses the perceptual pattern of how employees respond to a given processes and procedures, rewards and recognition and respect and dignity as it affects distributed members of a software development team.

3.1 THEORIES ON PERCEPTUAL PROCESS

3.1.1 THE SOCIAL INFORMATION PROCESSING MODEL

The social information processing model, developed in 1978 by Salancik and Pfeffer states that factors other than the core dimensions influences how employees respond to the design of their jobs. which is influenced by social information (infor- mation from other people) and by the employees` past beha- viours.

In a typical social environment employees exposed to informa- tion regarding aspects of their job design and work outcome pay attention to some aspects and ignore others. The design of

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 1, January-2013

ISSN 2229-5518

11

the member’s job such as kind of work, role within the project, knowledge required delivering given work, socio-political scenario of the location and rewards determine perceptions. As Distributed environment requires working together with other individuals the model suggests that the social environ- ment provides information on how members should evaluate their jobs and work outcomes.

3.1.2 SOCIAL INFORMATION PROCESSING (SIP) THEORY

Joseph Walther developed this theory in 1992. SIP is an inter- personal communication theory that suggests how individuals process information to develop into interpersonal relation- ships. Relational communication between team members hap- pens either face to face or as computer mediated communica- tion (CMC), once personal relationships are established, they demonstrate the same relational dimensions and qualities de- spite being distributed.

When distributed members start working on a common project, they start forming an impression about each member distributed across locations based on skill, capability, commu- nication, modesty and professional ethics. Their conversations and other paralinguistic cues such as posture, gesture, facial expression, vocal and nonverbal cues helps in inferring cha- racteristics of other members.

3.1.3 ATTRIBUTION THEORY

Knowledge workers are found to be highly conscious of self development and self image. Attribution theory (Weiner, 1980,

1992) concerns ways in which people explain (or attribute) the behaviour of others. The motivation of a member at the loca- tion of assignment depends on perceptions of successes or failures of the assignment. This determines the amount of ef- fort people are willing to put into the assignment in future. Socio-cultural factors contribute to perceptual factors for a member as it often offers challenges of being part of a distri- buted team in a strange location, with strange people, lan- guages, culture, values and procedures and processes.. Ac- cording to the attribution theory, explanations that people make on experiences of success or failure can be analyzed in terms of three sets of characteristics: The cause of the success or failure in a given situation may be internal( originating from within)or external(originating from the environment).It could be either stable or unstable. If stable, the outcome is like- ly to be the same during all occasions, and if unstable, differ- ent on other occasions. It could also be controllable or uncon- trollable. A controllable factor is one in which we believe we ourselves can alter. And an uncontrollable factor is one that we do not believe we can easily alter.

3.1.4 SELF-WORTH THEORY

This theory is very important to the study as the theory dis- cusses how individuals perceive role related efficacy and out- come behaviours. Self worth (Covington, 1984) combines’ ideas related to members self-efficacy, attribution theory, and learned helplessness. It focuses on the notion that people are largely motivated to do what it takes to enhance their reputa- tion in whatever location and assignment they are in. Distri- buted members engage in objectively counterproductive activ-

ities such as setting goals that are far too high or too low, re- ducing effort, and procrastinating. and non-cooperation with the team members. Knowledge workers have a high opinion of themselves (Ashish et al., 1999) with a can do attitude. The flip side however is that many feel that they are not treated well and paid equitable salaries and hence justifies their per- ceptions.

3.1.5 SOCIAL EXCHANGE THEORY

Social psychology and organizational research has supported the view that social interaction between professionals stimu- lates and reacts on various issues related to decisions (Blau,

1968). This social exchange goes beyond constraints of socio- cultural and political struggles of a distributed employee and includes organization culture to determine relationships be- tween managers, supervisors and team members. This can be described in terms of LMX, WGX, and TMX. Distributed soft- ware development has given a renewed face to social ex- change as acceptance of members working in the midst of con- straints has become a process of accepting global culture. De- fined by Harold H. Kelley and John W. Thibaut, (1959) claim that all human relationships have costs and rewards. SET states that people weigh the costs and rewards of a relation- ship to determine its worth. People strive to minimize costs and maximize rewards and then base the likeliness of devel- oping a relationship with someone on the perceived possible outcomes. In a social interaction costs and rewards can be interpreted as cause and effect. Activites with a positive effect, are considered generating positive perception and vice versa. Social exchanges are obligations in a social context are not clearly specified in advance and may not involve calculations but based on perceptions. Perception of fairness also plays a major role in social exchange situations. Since work teams have high levels of task and goal interdependence, members are forced to cooperate. Social exchange mechanisms may in- stigate cooperation among members through reciprocity of task and interpersonal assistance.

Social exchange takes place between different organisms, a living entity within the organization. Organization structures encompass a process of delivering the common objective of the organization. People interact vertically and horizontally within the organization.

3.1.6 LEADER MEMBER EXCHANGE (LMX)

Leaders and members in distributed teams are spread across different locations, and influenced by location constraints. Leaders establish relationships with various groups of subor- dinates. One group, referred to as the in-group, is favoured by the leader. Leaders treat their equals and subordinates diffe- rently at varying degrees and levels contingent on whether they are part of the in-group (high-quality relationship) or out- group (low-quality relationship) (Graen and Scandura, 1987). This theory is further strengthened by the cultural differences found in distributed teams. Managers of distributed organiza- tions follow a typical local model of treating employees. The theory asserts that leaders do not interact with subordinates uniformly (Graen and Cashman, 1975) because supervisors

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 1, January-2013

ISSN 2229-5518

12

have limited time and resources. The role determines whether someone is a leader or a member in a distributed software de- velopment. Distributed members (“In-group” or out-group) members perform their jobs in accordance with the principles of distributed employment procedures and can be counted on by their team members to perform structured tasks, maintain mutual communication to volunteer for extra work, and to share additional burdens or take on additional responsibilities. The relationship between leaders and followers follows three stages:

• Role taking: When a new member joins the organization, the leader assesses the talent and abilities of the member and offers them opportunities to demonstrate their capa- bilities.

• Role making: An informal and unstructured negotiation on work-related factors takes place between the leader and the member. A member who is similar to the leader is more likely to succeed. A betrayal by the member at this stage may result in him being relegated to the out-group

Leaders or coordinators have to exchange available re- sources with the team members to fulfil the structured tasks (Graen and Cashman, 1975). As a result, research shows that positive support, informal interdependencies, greater job lati- tude, common bonds, open communication, knowledge trans- fer, satisfaction, and shared loyalty exist (Dansereau, Graen, and Haga, 1975; Dienesch and Liden, 1986; Graen and Uhl- Bien, 1995).

The exchange between distributed members (superior- subordinate-dyad) is a two-way relationship and is the basic premise and unit of LMX analysis . This research investigates the quality of the relationship between LMX on team mem- bers’ perception of organizational justice and OCB. Previous studies have examined the construct of citizenship behaviour based on leaders’ reports. Wayne and Green (1993) investigate the effects of LMX on employee citizenship behaviour from the standpoint of the member rather than the leader. This re- search extends and builds on Wayne and Green’s study. Theories on team process include important assumptions, in- teractions and exchange behaviours of members working in teams. It primarily discusses the behavioural pattern of how employees interact and exchange their views and perceptions on given processes, procedures, rewards and recognition and respect and dignity. It also examines how individual percep- tions in the context of a team become a shared perception re- sulting in outcome behaviour.

3.2 TEAMS IN SOFTWARE ORGANIZATIONS

Teams are an important part of every software organization as software development is a focused activity which involves more than one individual. The use of teams allows for exper- tise in multiple areas as members are brought together with diverse knowledge, skills and abilities (Rouse, Cannon-Bowers

& Salas, 1992). When working in a team, members interact dynamically and exchange information which helps in better performance. Dispersed teams benefit organizations by pro- viding greater accessibility of knowledgeable employees while

keeping expenses down (Cascio, 1999). In this way an organi- zation operating from India, can access talents anywhere in the world at no extra cost.

Lisa Kimball in a speech described how teams have changed over a period of time. According to her the nature of teams have changed significantly because of changes in organiza- tions and the nature of the work they do.. Relationships be- tween people inside an organization and those previously considered outsiders (customers, suppliers, managers of colla- borating organizations, other stakeholders) are becoming more important. Several Organizations have discovered the value of collaborative work with a focus on knowledge man- agement.

These changes have influenced how teams are formed and operate as is mentioned below (Table 2)

Table 2-Changes perceived in contemporary teams

From | To |

Fixed team membership All team members drawn from within the organiza- tion Team members are dedicat- ed 100% to the team Team members are co- located organizationally and geographically Teams have a fixed starting and ending point Teams are managed by a single manager Organization follows uni- form organizational processes and procedures across teams | Mobile and shuttling team membership Team members are drawn in one or more than one out- side the organization (clients, collaborators, soft- ware vendors and profes- sional service providers) Most members are part of multiple teams Team members are distri- buted organizationally and geographically Teams form and reform con- tinuously Teams have multiple report- ing relationships with differ- ent parts of the organization at different times Geographical location de- termines processes and pro- cedures across teams |

Numerous studies have been conducted on teams, software development teams, distributed teams and virtual teams. While distributed teams have become a necessity for the ex- pansion of business and to meet the growing need, researchers have found that distributed teams have been shown to make better decisions (Chidambaram & Jones, 1993) when the task was not complex and members could freely interact with each other and had enough time to work.

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 1, January-2013

ISSN 2229-5518

13

3.2.1 RESEARCHES ON WORK TEAMS

A group of people who interact and exchange information and resources to achieve a shared objective of a common goal is called a work team. Sundstrom et al., (1990) say that a work team is an interdependent collection of individuals who share responsibility for specific outcomes for their organizations. Teams can have a positive impact on the organizations pro- duction and productivity (Antoni, 1991; Cappelli, Bassi, Katz, Knoke, Ostermann, & Useem, 1997; Guzzo & Dickson, 1996). This has been further demonstrated in Applebaum & Batt, (1994) study which states that teams are said to contribute to better outcomes for business organizations due to improved performance of employees. Work teams also stand committed to the organization’s objective as has been found in studies by Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski, & Erez, (2001); Osburn, Mo- ran, Musselwhite, & Zenger, (1990); Wellins, Byham, & Wil- son, (1991).

Researchers have tried to study the outcomes of work teams from different dimensions and have found out that work teams improves productivity (Glassop, 2002; Hamilton, Nick- erson, & Owan, 2003), Work teams improves performance ( Applebaum & Batt, 1994), work teams improve organizational responsiveness and flexibility (Friedman & Casner-Lotto,

2002), it adds up to morale and job satisfaction (Cordery, Mueller, & Smith, 1991; Dumaine, 1990; Goodman, Davadas,

& Hughson, 1988; Hackman, 1987; Lewis, 1990; Stewart, Manz,

& Sims, 2000) and work teams contribute to the commitment

of the organization ( Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski, & Erez,

2001; Osburn, Moran, Musselwhite, & Zenger, 1990; Wellins, Byham, & Wilson, 1991).

There are different factors which affect work teams (Table 3) performance. Sundstrom et al. (2000) have classified the fac- tors into five types.

Table 3- Factors affecting team performance

Intra group process Communication outside the group and external interac- tion

3.2.2 RESEARCH ON SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT TEAMS

“There is no substitute for careful planning and team forma- tion if overruns and later confusion, not to mention disaster, are to be avoided.” John S. MacDonald, MacDonald Dettwiler (2011). Many scholars have attempted to study software de- velopment teams in the context of project management. Walk- er Royce (1998) said that “Team work is much more important than the sum of the individual”. Ho Tsoi (1999) identified good management control system as a means to satisfy the project objectives. Researchers have found many variables affecting performance outcomes. The following variables have been studied in the context of software development teams Van Genuchten (1991) project execution, effectiveness was studied by Jiang & Klein (2000), goal achievement as a variable was explored by Sheremata, (2002), processes and perfor- mance was researched by Sawyer & Guinan, (1998).

Other variables (Table 4) studied in the context of software

development teams are as follows:

Table 4- Software development teams-variables studied

Work team context | Factors affecting perfor- mance |

Organizational context | Type of job, role, rewards and recognition, location, supervisory behaviour, op- portunity for a higher learn- ing and development, orga- nizational branding and im- age, global exposure and innovation |

Group composition | Group members' average cognitive ability, group hete- rogeneity, team size, func- tional diversity, personality traits, and group tenure |

Group work design | Interdependence between the team members |

Intra group process | Group cohesiveness and col- lective efficacy, conflict, col- laboration, norms and team member’s affect |

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 1, January-2013

ISSN 2229-5518

14

3.2.3 RESEARCH ON VIRTUAL TEAMS

Virtual teams are groups of dispersed employees who work with a shared objective and technology-supported communi- cation. Lipnack and Stamps (1997) defines a virtual team as ‘‘a group of people who interact through interdependent tasks guided by a common purpose’’ and work ‘‘across space, time, and organizational boundaries with links strengthened by webs of communication technologies.’’ Many interpretations have been used in defining virtual teams- some have said that virtual teams are divided by distance and never meet in per- son (Canney Davison and Ward 1999, Jarvenpaa et al. 1998, Kristof et al. 1995). However, the industry has moved forward and has adapted to global video conferencing and personal meetings but most refer to a virtual relationship as one that is conducted over technology (Geber 1995, Melymuka 1997b, Townsend et al. 1996, Young 1998).

Distributed members need to build their network with coun- terparts who are part of the team in contributing to common tasks. They interact and exchange to enable timely delivery of the given project. Managers from around the world build close networks and interact intensively to achieve a global strategy’s potential, functions served well by global virtual teams (Adler

1997, Bartlett and Ghoshal 1989). Global companies prefer to integrate the resources available to them (Bartlett and Ghoshal

1989, Ghoshal 1987, Kobrin 1991, Kogut 1985). Virtual teams allow companies to procure the best talent without geographi- cal restrictions (Ale Ebrahim, N., Ahmed, S. & Taha, Z., 2009). However despite all these studies empirical research is li- mited.

3.2.4 GLOBALLY DISTRIBUTED TEAMS

The world is becoming a global village as the need for organi- zations providing substantial availability to global customers becomes a necessity. Many scholars have found a marginal difference between globally distributed teams (GDT), virtual teams and open source teams. Software development teams are increasingly spread across multiple countries (Carmel

1999) to take advantage of resources at local sites. Although scholars have studied teams independently, distributed teams share a unique pattern of prevailing on software development process across the globe (Sarker & Sahay, 2004). In today’s complex business environment, these teams enable greater organizational flexibility and the ability to respond quickly to change. Collaborative software development (Barkhi, Amiri & James, 2006), global software development (Herbsleb & Moi- tra, 2001) collaborative software development (Barkhi, Amiri

& James, 2006) and distributed software development (Lay- man, Williams, Damian, & Bures, 2006) are terminologies used to denote the geographical dispersion in software develop- ment teams. This is particularly important in global software development because of the rapidly changing system re- quirements. In a global software development scenario, of interest would be to watch the sourcing of a project, the forma- tion of teams, and distribution of teams between locations, following the software development process, and delivering business expectations and sustaining the business for the or- ganization.

3.3 CENTRIFUGAL FORCE OF GDT

Herbsleb and Moitra (2001), list down factors which have fu- elled the growth of global software development teams. In- dustries across the world respond positively to the distributed method of working. Andres (2002) assessed the usefulness of videoconferencing as a support mechanism for geographically dispersed software development teams. Distributed team is characterized by geographic dispersion, reliance on electronic media, and national diversity (Carmel 1999; Griffith et al.

2003), which form “a centrifugal force that propels team mem- bers apart from each other,” causing breakdowns in commu- nication, coordination, control, and cohesion (Carmel and Tjia

2005). Although an increasing number of organizations are relying on technology-enabled geographically distributed teams (McDonough et al. 2001), these teams are often difficult to manage and fall short of performance expectations. Process of creating and managing a globally distributed team is time consuming and needs more than one skill (Herbsleb & Grinter,

1999).

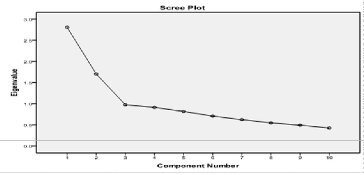

3.4 VARIABLES STUDIED IN THE PAST

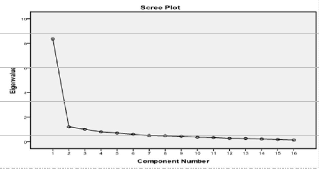

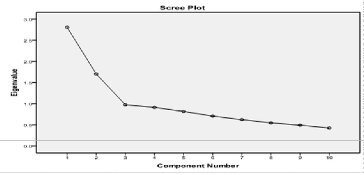

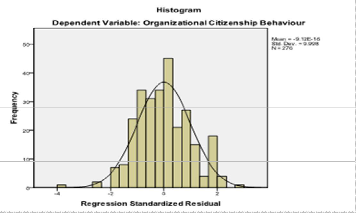

A study on the Meta-analysis of globally distributed and vir- tual teams by Martin et al.,(2004) reviewed 109 articles. To increase the depth and breadth of the research 99 articles and white papers from 2004 to 2011 on globally distributed teams, software development teams, open source teams and virtual teams were reviewed. Although earlier studies were limited to university settings, current reviews found studies with indus- trial and IT settings.. Researchers have also listed problems that arise due to physical dispersion among project members and classified them under different dimensions of strategic, cultural, communication, project and process management, knowledge management and technical.