network’s resources inefficiently. For computer

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 5, Issue 12, December-2014 1373

ISSN 2229-5518

Impact of Shadow Banking In People's Republic of China

Zaid Bin Jawaid1, Professor Zhang Donghui2, School of Economics, Shandong University, Shandong, PRChina

Index Terms— Credit Risk, Shadow Banking, Maturity, Lerverage, Liquidity

—————————— ——————————

network’s resources inefficiently. For computer![]()

The term “shadow bank” was coined by economist Paul

McCulley in a 2007 speech at the annual financial sympo-

sium hosted by the Kansas City Federal Reserve Bank in

Jackson Hole, Wyoming. In McCulley’s talk, shadow bank-

ing had a distinctly U.S. focus and referred mainly to non-

bank financial institutions that engaged in what econo-

mists call maturity transformation. Commercial banks en-

gage in maturity transformation when they use deposits, which are normally short term, to fund loans that are long- er term. Shadow banks do something similar [1].

Shadow banks first caught the attention of many experts because of their growing role in turning home mortgages into securities. The “securitization chain” started with the

origination of a mortgage that then was bought and sold by one or more financial entities until it ended up part of a package of mortgage loans used to back a security that was sold to investors. The value of the security was related to the value of the mortgage loans in the package, and the interest on a mortgage-backed security was paid from the interest and principal homeowners paid on their mortgage loans. Almost every step from creation of the mortgage to sale of the security took place outside the direct view of regulators.

In current era, communication networks are growing, de- veloping and evolving at a rapid rate. Telecommunication systems provide a myriad of services that use much of the

• 1Zaid Bin Jawaid is master student of MSC Economics in School of Eco- nomics, Shandong University, Shandong China. He can be reached on zaid.ch@hotmail.com; 008618769770350.

• 2Professor Zhang Donghui, Professor, School of Economics, Shandong

University, Shandong, China

systems to optimize their own performance without hu- man assistance, they need to learn from experience. Achieving good performance in such a network using fixed algorithms and hand-coded heuristics is very diffi- cult and prone to inflexibility. Instead, we used reinforce- ment learning which is efficient, robust, and adaptable in intelligent routing.

Under this definition shadow banks would include broker- dealers that fund their assets using repurchase agreements (repos). In a repurchase agreement an entity in need of funds sells a security to raise those funds and promises to buy the security back (that is, repay the borrowing) at a specified price on a specified date. Money market mutual funds that pool investors’ funds to purchase commercial paper (corporate IOUs) or mortgage-backed securities are also considered shadow banks. So are financial entities that sell commercial paper and use the proceeds to extend cred- it to households (called finance companies in many coun- tries).

IJSER © 2014 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 5, Issue 12, December-2014 1374

ISSN 2229-5518

As long as investors understand what is going on and such activities do not pose undue risk to the financial system, there is nothing inherently shadowy about obtaining funds from various investors who might want their money back within a short period and investing those funds in assets with longer-term maturities.

Problems arose during the recent global financial crisis,

however, when investors became skittish about what those

longer-term assets were really worth and many decided to

withdraw their funds at once. To repay these investors, shadow banks had to sell assets. These “fire sales” general- ly reduced the value of those assets, forcing other shadow banking entities (and some banks) with similar assets to reduce the value of those assets on their books to reflect the lower market price, creating further uncertainty about their health. At the peak of the crisis, so many investors withdrew or would not roll over (reinvest) their funds that many financial institutions—banks and nonbanks—ran into serious difficulty.

Had this taken place outside the banking system, it could possibly have been isolated and those entities could have

been closed in an orderly manner. But real banks were caught in the shadows, too. Some shadow banks were con- trolled by commercial banks and for reputational reasons were salvaged by their stronger bank parent. In other cas- es, the connections were at arm’s length, but because shadow banks had to withdraw from other markets— including those in which banks sold commercial paper and other short-term debt—these sources of funding to banks were also impaired. And because there was so little trans- parency, it often was unclear who owed (or would owe later) what to whom.

In short, the shadow banking entities were characterized by a lack of disclosure and information about the value of their assets (or sometimes even what the assets were); opaque governance and ownership structures between banks and shadow banks; little regulatory or supervisory oversight of the type associated with traditional banks; virtually no loss-absorbing capital or cash for redemptions; and a lack of access to formal liquidity support to help prevent fire sales

Shadows can be frightening because they obscure the shapes and sizes of objects within them. The same is true for shadow banks. Estimating the size of the shadow bank- ing system is particularly difficult because many of its enti- ties do not report to government regulators. The shadow banking system appears to be largest in the United States, but nonbank credit intermediation is present in other countries—and growing. In May 2010, the Federal Reserve began collecting and publishing data on the part of the shadow banking system that deals in some types of repo lending. In 2012, the FSB conducted its second “global” monitoring exercise to examine all nonbank credit inter-

mediation in 25 jurisdictions and the euro area, which was mandated by the Group of 20 major advanced and emerg- ing market economies. The results are rough because they use a catch-all category of “other financial institutions,” but they do show that the U.S. shadow banking system is still the largest, though it has declined from 44 percent of the sampled countries’ total to 35 percent. Across the juris- dictions contributing to the FSB exercise, the global shad- ow system peaked at $62 trillion in 2007, declined to $59 trillion during the crisis, and rebounded to $67 trillion at the end of 2011. The shadow banking system’s share of total financial intermediation was about 25 percent in

2009–11, down from 27 percent in 2007. But the FSB exer-

cise, which is based on measures of where funds come

from and where they go, does not gauge the risks that

shadow banking poses to the financial system. The FSB

also does not measure the amount of debt used to pur- chase assets (often called leverage), the degree to which the system can amplify problems, or the channels through which problems move from one sector to another. There are plans to combine the original “macro mapping” exer- cise with information gathered from regulatory and super- visory reports and information gleaned from the markets about new trends, instruments, and linkages. The FSB plans to use what it learns about shadow banks and link that information to the four shadow banking activities (maturity and liquidity transformation, credit risk transfer, and leverage) to devise a “systemic risk map” to determine which activities, if any, may pose a systemic risk.

The first FSB survey suggested that homegrown shadow banking activity is not significant in most jurisdictions, although it did not take into account cross-border activi- ties. Nor was it able to show how the activities might be connected across different types of entities. For example, finance companies in some countries seem to be extending their reach and their credit intermediation role. As yet, the true risks of these activities and whether they are systemi- cally important are undetermined.

The official sector is collecting more and better information and searching for hidden vulnerabilities. Banking supervi- sors also are examining the exposure of traditional banks to shadow banks and trying to contain it through such av- enues as capital and liquidity regulations—because this exposure allowed shadow banks to affect the traditional financial sector and the economy more generally. Moreo- ver, because many shadow banking entities were either lightly regulated or outside the purview of regulators, the authorities are contemplating expanding the scope of in- formation reporting and regulation—of both entities and the markets they use. And the authorities are making sure that all potential shadow banking entities or activities are overseen in a way that discourages shadow banks from tailoring their behavior to come under the supervision of

IJSER © 2014

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 5, Issue 12, December-2014 1375

ISSN 2229-5518

the weakest (or of no) regulators—domestically or global- ly. The authorities are making progress, but they work in the shadows themselves—trying to piece together dispar- ate and incomplete data to see what, if any, systemic risks are associated with the various activities, entities, and in- struments that comprise the shadow banking system.

Before getting into an analysis of how the shadow bank- ing system played a role in the 2008 economic downturn, we must first understand what this system is in the most basic sense. Although the term "shadow" may conjure up all sorts of nefarious and unpleasant images in one's mind, it would simply be unfair to characterize this aspect of our financial system in such an emotional or negative context.

We all know the traditional banking system provides checking and savings accounts, auto and home loans, and various other financial services. But most people fail to understand that these institutions do not possess infinite capital, and are therefore limited in the amount of loans they can provide to consumers or small businesses. This limitation is where the shadow banking system came into play.

Prior to the Great Recession, banks realized their ability to profit from lending was limited by access to capital and the size of their balance sheet. So instead of lending and hold- ing loans like banks did in the "good old days" (limiting profit potential), they began specializing in originating loans, packaging them and selling them to other investors through securitization processes via investment banks; hence the inception of the unregulated "shadow banking system" which provided a conduit capital seeking to pur- chase these securities.

How this worked is rather simple. A financial institution would lend as much money as possible for home, general consumer and auto loans, and would then work with in- vestment bankers to securitize these pools of assets. These securities would then be sold to a variety of investors such as pension funds, endowments, mutual funds, hedge funds and other financial institutions; these were the fun- ders of the shadow system. These instruments could take a great many forms such as asset-backed securities (ABS), collateralized debt obligations (CDO), mortgage- backed securities (MBS) [2]. It was through these instruments that more and more peo- ple were easily able to access credit as financial institutions could profit from making ever increasing amounts of risky loans. This led to the lending institutions selling these loans to other investors in the form of innovative fixed- income securities. So it seemed a win-win situation for everyone involved. Consumers got the cheap credit they

desired and investors found a way to earn higher returns over Treasuries with minimal perceived risk in the face of robust and stable economic growth.

So if this was such a good thing, how did it turn so ugly? Well the answer to this question centers on one very per- sistent aspect of investor behavior in that people tend to extrapolate current events too far into the future. In this particular instance, investors implicitly believed through their pricing of risks (or required credit spread over Treas- uries) that the economic stability we enjoyed during the mid 2000s would persist. Premiums investors required for bearing the credit risks associated with MBSs, CDOs, ABSs etc., were not priced accordingly for the level of underly- ing risk. This relationship can be dimensioned by using the proxy of falling credit spreads between the U.S. 10-Year Treasury and Moody's AAA rated corporate bonds as demonstrated in Figure 1. (Despite investor distrust, rating agencies can be helpful. Just be sure you use these ratings as a starting point.

Fig 1: Spread Between Moody's AAA and U.S. 10-Year Treasury

The question then turns to what went wrong and why did investors sour so precipitously on what had become an apparently successful means to provide easy access to credit for the average American and bolster investor re- turns? The answer to this question is rather simple in that it involves the relationship between leverage and the cost thereof.

Although Americans were more than happy to have easy

access to credit cards, cars and home loans, it is unlikely

they were aware this practice was placing the U.S.'s socie-

tal balance sheet in the most precarious position in its en-

tire history. As you can see from Figure 2, total leverage in American society had not only reached its highest levels in history, but had done so at an accelerating pace in recent years. The result was our economy had become extremely

IJSER © 2014

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 5, Issue 12, December-2014 1376

ISSN 2229-5518

addicted to leverage and overburdening unrealistic budget practices.

Fig 2: Total Societal Leverage (Household, Farm, Corp. Government and Financial) - June 2007[3]

One of the many problems in hindsight is that the Federal Reserve failed to take into consideration not only the in- credible leverage inherent in our economy, but the reliance on low interest rates. Corporations were not the only par- ties dependent on low interest rates, home owners could only pay off their mortgage if rates remained low. Thus, they could not pay interest payments on their mortgages that exceeded the initial teaser rate. The shadow banking system enabled such a system to flourish because many of these economic anomalies remained hidden in the unregu- lated market [4].

So with the dual effect of high 2008 energy costs (recall

gasoline at around $4 per gallon) alongside the higher in- terest rates that followed the mortgage teaser rates, the economy began to sputter. But more importantly, investors began to discount a recession into their pricing of securities and willingness to bear risk. This in turn created a positive feedback loop that hit the economy with higher credit costs as investors’ now required greater compensation for bear- ing risk given the fragility of the U.S. economy and peo- ples' ability to service their interest payments. See Figure 3.

Fig. 3: Spread Between Moody's AAA and U.S. 10-Year

Treasury

So the end of result of this confluence of events was exactly what the economy did not need. Investors were far less likely to lend money over fears over economic weakness and the shadow banking system essentially collapsed. So any lending that did take place was done at far higher in- terest rates than people were accustomed to. On top of this, the highly levered U.S. economy was not only unable to bear these precipitous increases in interest rates, but the lack of availability of credit in general. This is what led to the precipitous decline in U.S. economic activity, or the "Great Recession."

Fig. 4: Total Borrowing/Lending in U.S. Economy And An- nualized Real GDP Growth

The point of this article is two-fold. The first is to serve a big picture history lesson for what the shadow banking system was, what caused its failure, how that failure con- tributed to the 2008 economic woes, and also to provide a demonstration of how important this system is to our economy given societal leverage. Albeit people always seek to demonize someone or something when things go wrong, it's important to remember that the shadow bank- ing system could never have existed if there had been no demand for its services - the demand created the supply. Like it or not, this aspect of our economy is essential given country's penchant for borrowing to support consumer spending. Can we regulate it for the betterment of society and preclude such future meltdowns? Well, that remains to be seen.

In the town of Jingjiang, a few hours’ drive from Shanghai, Yangzijiang Shipbuilding is making 21 huge container ships for Seaspan, a Canadian shipping firm. An enormous sign declares, “We want to be the best shipyard in China.”

IJSER © 2014 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 5, Issue 12, December-2014 1377

ISSN 2229-5518

It is certainly among the most profitable, earning 3 billion Yuan ($481m) last year. But only two-thirds or so of that came from building ships. The rest came from lending money to other companies using a local financial instru- ment called an entrusted loan. This puts Yangzijiang at the forefront of another industry: shadow banking.

A decade ago, conventional banks, which are almost all state-owned and tightly regulated, accounted for virtually all lending in China. Now, credit is available from a range of alternative financiers, such as trusts, leasing companies, credit-guarantee outfits and money-market funds, which are known collectively as shadow banks. Although many of these lenders are perfectly respectable, others constitute blatant attempts to get around the many rules about how much banks can lend to which companies at what rates.

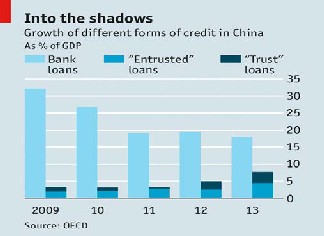

Although bank lending remains far bigger than the shad- owy sort and is still expanding at an astonishing pace, its rate of growth has recently stabilized. The growth of some

of the more worrying forms of shadow lending, in con- trast, is accelerating (see chart). Shadow banks accounted for almost a third of the rise in lending last year, swelling by over 50% in the process.

Thus far, most of the concerns about shadow banking in China have centred on trusts. By offering returns as high as 10%, they raise money from businesses and individuals frustrated by the low cap the government imposes for in- terest rates on bank deposits. The interest they charge to borrowers, naturally, is even higher. They lend to firms that are unable to borrow from banks, often because they are in frothy industries, such as property or steel, where regulators see signs of overinvestment and so have in- structed banks to curb lending. Over two-fifths of Yangzi- jiang’s loans go to property developers in smaller Chinese cities; land makes up nearly two-thirds of its collatral.

China’s economy is slowing. It has grown by 7.6% for the past two years, the slowest rate since 1990. Several trust products have defaulted, although investors in most of

them have got their money back one way or another. Over

$400 billion-worth of trust products are due to mature this

year—and borrowers will want to roll over many of those

loans. Many observers worry that investors will lose faith

in trusts, prompting a run, which may, in turn, blight cer- tain industries and other parts of the financial system. No country, pessimists point out, has seen credit in all its forms grow as quickly as China has of late without suffer- ing a financial crisis.

One reason for optimism is that trusts are regulated by the same agency that supervises banks, the China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC). This argues Jason Bed- ford, an independent expert who used to audit trust com- panies, means the CBRC can tell not only whether the trusts themselves are wobbly, but also how any wobbles would affect banks. As our special report this week ex- plains, it and other regulators have recently strengthened oversight of trusts, requiring clearer accounting and limit- ing dealings with banks.

Now that regulators are tightening the screws on trusts, money is flowing to other, less closely watched intermedi- aries. “Shadow banking in China looks like a cat-and- mouse game,” declares Liu Yuhui, chief economist of GF Securities, a brokerage house.

For instance, the CBRC’s limits on the ways that banks and trusts could co-operate do not apply to securities houses. That has fuelled a boom in the assets these firms manage: they rose to 5.2 trillion yuan by the end of last year, up from 1.9 trillion yuan a year earlier. In some instances, the brokers are using loans originated by banks to back “wealth-management products” they sell to investors themselves; in others, they are acting as intermediaries to allow trusts to do the same, in spite of the new rules. These maneuvers, in effect, allow banks to sidestep various re- strictions on their lending.

Trust beneficiary rights products (TBRs) are another way around the restrictions on dealings between banks and trusts. A bank sets up a firm to buy loans from a trust; it then sells the rights to the income from those loans to the bank—a TBR is born. The bank can then sell the TBR to another bank. The intention, Mr. Bedford says, is often to make risky corporate loans look like safer lending between banks, thereby evading capital requirements and mini- mum loan-to-deposit ratios, among other rules.

Entrusted loans are yet another fast-growing form of shadow banking. These involve cash-rich companies, often well-connected state-owned enterprises (SOEs), lending to less well-connected firms. There are so many SOEs now competing with Yangzijiang to offer loans, reports Liu Hua, the shipbuilder’s chief financial officer, that her firm has been forced to reduce the interest rates it charges from around 15% a year to closer to 10% a year.

IJSER © 2014 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 5, Issue 12, December-2014 1378

ISSN 2229-5518

Such loans, often made using banks as intermediaries to get around regulations forbidding such lending, expose the financial sector to yet more risk. The value of new en- trusted loans in March was 239 billion Yuan, up 64 billion from a year earlier. Companies borrowed 716 billion Yuan via entrusted loans in the first three months of the year; corporate bond issuance over the same period amounted to only 385 billion Yuan [4].

Entrusted loans are not the only way companies are lend- ing to one another. Hangzhou, home to Alibaba and many other entrepreneurial outfits, is one of China’s richest cit- ies, but it is now undergoing a quiet financial crisis. Its many small steel and textile entrepreneurs found it hard to get loans from official banks, so they banded together. Re- ports suggest that firms guaranteed one another’s debts, forming a web of entanglements that helped everyone get credit during good times. But now, with the economy slowing, the weaker firms are beginning to default, drag- ging healthy ones down too.

Steel traders in Guangdong, chemicals firms in Zhejiang and coal miners and energy firms in Shanxi appear to have developed similar networks. Xinhua, China’s official news agency, has reported that in some of these industries the guarantees invoked have spread from the “first circle” of firms vouching for the original defaulters to the “second” and “third” circles, meaning guarantors of the guarantors.

Just as a crisis in shadow banking could spread to the real economy, a sharp downturn in some sectors could cause trouble for shadow banks, leading to a broader financial mess. Many trust loans are secured with property, and many developers are reliant on shadow finance, but Chi- na’s raging property market is showing signs of cooling, especially in smaller cities. The fear is of a downward spi- ral in which the pricking of the property bubble leads to a panic in shadow finance, which reduces access to credit, pushing property prices and economic growth down fur- ther.

How bad could things get? IHS, a consultancy, recently predicted that such a property crash could reduce China’s GDP from a forecast 7.5% this year to 6.6%, and to 4.8% next year. That may not sound like the end of the world, but by China’s standards, it would be an alarming slow- down.

All this poses a genuine dilemma for China’s regulators. They have long desired to develop deep and versatile capi- tal markets, and shadow banking is a natural part of that. Indeed, there is an argument that China would benefit from the expansion of certain forms of shadow banking, such as the securitisation of loans.

Although some kinds of lending are clearly getting out of hand, the losses should be manageable. For all the subter- fuge Chinese shadow banks indulge in, their loans usually come with decent collateral. The biggest threat to the sys- tem is that by moving too forcefully to rein in shadow lending, regulators accidentally precipitate a run on shad- ow banks. Instead, they are moving warily, slowly ratchet- ing up regulation and allowing the occasional minor de- fault.

[1] Acharya, Viral V. & Schnabl, Philipp (2010). "Do Global Banks Spread Global Imbalances, Asset-Backed Commercial Paper during the Financial Crisis of 2007-09," IMF Economic Review, vol. 58.

[2] van Rossem, China: demons lurking in the shadows?, Retrieved from

https://blog.degroof.be/fr/article/china-demons-lurking-shadows,

2013

[3] Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Country Analysis Unit, (2013)

Shadow Banking in China: Expanding Scale, Evolving Structure, Asia

Focus.

[4] Sebastian Andrei, Shadow Banking In China and Its Implications In

The Global Financial Recession, China, 2012.

[5] Langfitt, China's 'Shadow Banking' And How It Threatens The Econ-

omy, published in National Public Radio, Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/blogs/parallels/2013/06/28/196617073/china s-shadow-banking-and-how-it-threatens-the-economy

IJSER © 2014 http://www.ijser.org